You Are All Terminators. (I Am Not.)

Way back in grad school— when VHS was a thing and computer screens were all monochrome and a 20-Megabyte hard drive was the kind of thing only supervillains could afford—a bunch of us rented “The Terminator” for the weekend and watched it between bouts of AD&D. Inevitably we came upon the iconic first-person T-800 view. You know the one: red visual field overlaid by scrolling columns of numbers, status reports and hardware ID codes, a kind of internal HUD giving a sense of how ol’ Arnie saw the world.

“Of course it wouldn’t really perceive things like that,” Steve Patton observed, because half the point of these events was to nitpick the shit out of everything. “All that data would be integrated further upstream.” And of course he was right. A T-800 wouldn’t have to read environmental data off an overlay any more than you or I would need to read a little digital thermometer in our visual field to know that it was “cold”. You couldn’t take that cyborg HUD literally; that would imply truly incompetent engineering, the addition of an unnecessary (and time-consuming) computational step. Best to regard it as a narrative convenience, like subtitles in a foreign film. Terminators don’t experience overlays any more than we do.

Except it turns out that maybe we do. Or at least, you do. Apparently most of you are computationally inefficient doofuses.

There’s this thing called aphantasia—“the inability to create mental imagery”, according to Wikipedia—whose victims don’t experience Terminator-like visual overlays. Honestly, I didn’t think anyone did that.

I mean, sure, “mind’s eye”: I have that, or at least I thought I did. I can imagine what things look like. I can close my eyes and think of anything from a dragon to a sapient raccoon; I can describe the color of the scales, the scruffiness of the fur. I can imagine what friends and loved ones look like, describe them with reasonable fidelity to anyone who might be listening. I thought that’s what people meant by “picturing something in your mind”.

But a literal image, like a floating window in a heads-up overlay? A visual hallucination that manifests like the “picture in picture” feature you get in TVs and computer monitors? That would be bullshit. Not only would such artifacts distract you from paying attention to your actual environment, but they would be computationally inefficient: a Terminator worldview. Surely all your mind’s eyes are integrated further upstream, like mine.

But apparently not. Apparently, when imagining things that aren’t there, 97% of you see the world through cluttered desktops. You literally see things. (You also hear things; while I merely imagine Morgan Freeman’s voice talking in my head, your dumb brains actually hear the dude as though he were talking to you via bone conduction.)

I still don’t believe this. And the BUG backs me up: she doesn’t hallucinate picture-in-picture either. So here’s an informal poll: let me know how you experience reality, and maybe I can start to wrap my head around this.

If this does prove to be true—if those of us who merely imagine are some kind of freakish minority—it might at least explain why some readers find my prose so confusing when I describe spaceship layouts and skiffy vistas. Maybe we literally experience different sensory modalities, and something gets lost in translation.

On the plus side, apparently us aphantics tend to have IQs 5-10 points higher than the rest of you, with pretty high statistical confidence (P=0.002). I suppose that makes sense.

We don’t waste brainpower on that extra computational step.

I mean, I would say I have the perception of seeing the things I imagine, so I would say I literally see them. But they are not in my visual field. Similar to dreaming.

That’s weird, because I definitely see things in my visual field while dreaming.

Yeah. Apparently, aphantasia does not rule out dreaming in pictures.

Same here; aphantastic when awake but not when asleep.

Peter, my name is Joshua Hyland and I recently discovered a short story that you must have wrote in 2010~ish stored on the “I” drive here at South Pole Station Antarctica. “The Things” is a fantastic story. I’ve read it almost every day since I discovered the copy. I want to share it with more people because the scanned PDF copy on the I drive is not great quality; whole sentences cut in half at the page breaks. I am under the impression that maybe you wrote that while you were at the South Pole? Is that right? Would you be willing to discuss “The Things”? I realize that this blog post is set up for other purposes. I don’t want to hijack it all the way, just a little bit. Thank you for writing “The Things” I am hooked. I will definitely be reading your other books/stories.

Ooooh, spooky!

And welcome, “Joshua”. I think you’ll find it stimulating here.

Hey Joshua,

I am profoundly tickled to read this. I’ve read that traditionally, after the last plane leaves for the season each year, the crew down there gathers round the TV for a showing of the various “The Thing” iterations. I’ve always thought that was very cool, and it pleases me no end that even a ratty bit-rotted copy of “the Things” somehow made it down there.

But if the copy really is crap, you do realize that I link to the Clarkesworld copy on the backlist page of this very website, yes? (Speaking of which, I see I haven’t added any new material to that page since 2018. I should probably get on that; I’ve put out a bunch of stuff since then.) I could even fire you off a proper pdf if you dropped me a line behind the scenes.

I don’t know the specific context in which you’re asking if I’d be willing to “discuss” the story—over beers, over videolink, or kidnapped, bundled into the back of a van, and interrogated—but in principle I’d be happy to. In fact, I’m answering a bunch of written questions about that story for someone’s university course right now.

This is kind of my experience, too – I have a very clear image of, say, an apple in my head, but it is not “in front” of me/my eyes – weirdly, it “feels” like it is “in the middle” of my head, yet it still feels “visual” – almost as if I had an extra pair of eyes in some kind of “inner chamber”, while my regular “visual field” is just whatever is in front of me. So not sure which box to tick in the poll.

Same here. I can imagine a visual situation and move through it. In fact, I’ve found doing so useful when there is a physical task I need to perform correctly, and don’t want the consequences of doing it incorrectly irl. But the visualization is not in my field of vision, it’s somewhere else in my head. And it takes processing power – my attention to what is in front of me is diminished.

So, also not sure which box to tick – maybe the third one, although I think someone needs to figure out a way to check the veracity of that category’s numbers.

Actually, reading what I just wrote, and looking at the categories again, I guess the middle one applies.

If you want to read up more on who’s researching on this, Joel Pearson at the Future Minds Lab at University of New South Wales seems to be about at the front from what I know.

An interesting recent bits, they’ve figured out a physical ‘tell’ for aphantasia. From what I gather, some of it seems obvious-in-hindsight but it’s relatively recent that it was identified as a concrete thing to research, so there’s catching-up to do.

By some of the measures I’ve seen, what you describe may be milder than what some people experience. For example, you’re able to “imagine what friends and loved ones look like, describe them with reasonable fidelity to anyone who might be listening”, whereas I’m terrible at even that. I can do memorized facts, “my wife has green eyes, brown hair”, etc. but I’d have trouble trying to hold a coherent concept in my mind to be able to describe with any sort of visual fidelity. Similarly, if you asked me to think of a raccoon I’d be able to go “raccoons are usually black, brown, and grey with various stripes” but I couldn’t tell you what the fur would look like.

So I think what you may be hitting on is the full Terminator-view as ‘hyperphantasia’, then a varying range of people somewhere in the middle that can imagine visually but it’s not outright an inner projection; and then people further along who don’t even have that much.

https://www.futuremindslab.com/extremeimagery

Hyperphantasia. OK, good to know. Although even if it’s not as widespread, the fact that the hyper variety exists at all is, to me, mind-blowing.

Thanks for the link!

Yes, but only in bursts of inspiration. I work as a semi conductor mixed signal layout engineer (the person who positions and connect the freaking transistors) and I’ve got to optimize a lot of variables while not falling afoul of the design rule checker.

Sometimes I’ll be be completely baffled and going home for the day and then the “little man upstairs” will signal a solution by overlaying the answer on my visual field while I’m driving at 100k.

Holy shit. You’re kidding, right? Tell me you’re kidding.

Because a visual artifact popping up to block your view at 100kph is exactly why I’d expect something like this to get weeded out real fast.

Not a joke. Not exactly a common occurence either, but frequent enough that when I’m completely bamboozled I’ll transit or Uber it home, in anticipation of a ‘pop up’

As far as natural selection is concerned, I don’t think we’ve been traveling at 100kph long enough for it to be weeded out, though I’ll defer to your expertise.

Nope, Greggles isn’t kidding.

The image can obscure what is really being seen, but more often it’s very, very much more interesting than reality and it takes up more attention.

This is why some famous geniuses have grad students and assistants looking after them. Most of the time a particularly bright genius gets around just fine, but when a sudden insight hits, that person had better not be driving or should be led away from hot stoves and kitchen knives.

Now, is there a difference between “overlaid on my visual field”, and “occupying bandwidth that is usually devoted to my visual field”?

I speculate that the former is a subset of the latter, and the overlay effect results from how some middle-management layer makes sense of it…

OK, I would like to be a philosophical zombie, but not this time.

I consider myself to have aphantasia because I can’t mentally picture objects very well, but I can do it slightly. I “literally see things” in the sense that they… are… visual… imagery… and are anchored onto a location in my visual field, and don’t “literally see things” in the sense that it requires a lot of attention to maintain the visual images and they don’t obstruct the things below them. Also, I can only do simple shapes and colors, especially with my eyes open.

Well, you do literally see stuff in your visual field, even if it takes effort. That’s more than I can do.

Your three option poll needs other options.

(A) I literally see an image in my visual field

(B) I see an image which I can distinguish from my visual field

(C) I can think of the image

(D) I can think about the image but not what it looks like

(E) I can remember that previously I really saw a real thing but I can’t describe the thing except with vague or memorized words

(F) I can’t remember a lot of real things I really saw but I can recognise them when I really see them again

(G) I can’t remember a lot of real things I really saw and I don’t recognise them when I really see them again

These are all experiences reported by people I’ve met, and most of the people are rather ordinary, ranging in intelligence. I’ve found that artists & makers are more likely to be in option (A) or (B), writers & makers in (B) or (C).

There are parallels in imagination for sounds and music.

Faces are an exception to ‘image.’ It is quite possible for a person to be in option (E), (F), or (G) when it comes to faces even though they may normally be in (A) or (B). It is also possible for a person to remember faces but be unable to recognise them when actually seeing them.

There are other experiences, too, outside the ordinary normal-ish expected experiences.

And if someone is truly inspiring, they can encourage others to imagine in option (B) or (A) for a few moments even if the others aren’t usually able to do it.

Some of us might switch between your options, depending upon circumstances. I tend towards option D when dealing with maps, for instance, but when I’m visualizing skulls (I am currently doing a lot of 3-D geometric morphometrics and it’s very visual at some stages of analysis), I tend towards option B. Same as when I’m recalling the details of study sites where I did field work. This may be a function of the amount of attention involved.

And of course, images with great emotional import can be recalled with considerable fidelity. This isn’t always good.

Artist (painter) here. I absolutely do not have imagined imagery cluttering my visual field, as in, I do not hallucinate while sober. However, I have an exceptionally good “mind’s eye” and visual memory (though not photographic), and am able to verbally describe what I am “seeing” in my gray matter and also draw it. I fantasize about witnessing a crime just so I can impress the police sketch artist with my detailed visual memory.

But Peter, I think you’re misinterpreting the “97%” from that link. A “visual experience” is just the mind’s-eye thing. An “experience” doesn’t have to mean sensation/perception (in the strict sense).

That would have been my original take on it too. But some of the stuff I’ve read suggests that the literal PiP aspect is really a thing.

Although given the responses so far, you may be right that I’m misinterpreting the 97% as the proportion of PiPers.

Huh. Where were you when I was writing this thing up?

That would have made a more nuanced survey, for sure. But my immediate goal was to find out how many of you (if any) perceived literal visual stimuli of any kind in the course of imagination, regardless of the effort involved or the detail perceived. Any such perception, however rudimentary, would just seem wild to me. (And while it does seem to be a much smaller proportion than the literature suggests, the fact that 12% of you answered in the affirmative is—enlightening and disturbing in equal measure.)

I wouldn’t worry too much about the results from your poll. They’re going to be driven as much by confusion over which answer is the best description of the individual’s experience, as by the individual’s actual experience.

For me default mode is imagining the item, but with effort I can get an image going.

Things that can cause that effort – illness, drugs, really amazing prose.

I would say that I am similar to Don. I can imagine things in my mind’s eye, but it never overlays in my actual visual field. I have to switch between or juggle the two as separate entities. For dreaming, I have never noticed any kind of overlay. It’s all just one image that I seem to be seeing, but if I have any kind of lucid dreaming I can switch to my mind’s eye and change the set-up, after which I go back to perceiving it as if it is my visual field.

Wording is tricky with eliciting descriptions of this stuff, in my experience — I’ve found this tweet helpful: https://twitter.com/backus/status/1091203973246111744?lang=en

Number 6 is closest, but contaminated by the fact that I couldn’t read the tweet without also having glimpsed the image beneath it. My star was a much purer red than 6, but it also wasn’t a 2D array of pixels; it was something more like a set of abstract instructions for constructing a red star in a 2D pixel array. Because I’d seen the image on the tweet, my star initially had number of points, orientation, proportions etc like the one in the image. Being annoyed at that obvious suggestion via availability bias, I subsequently gave it 8 points instead of 5.

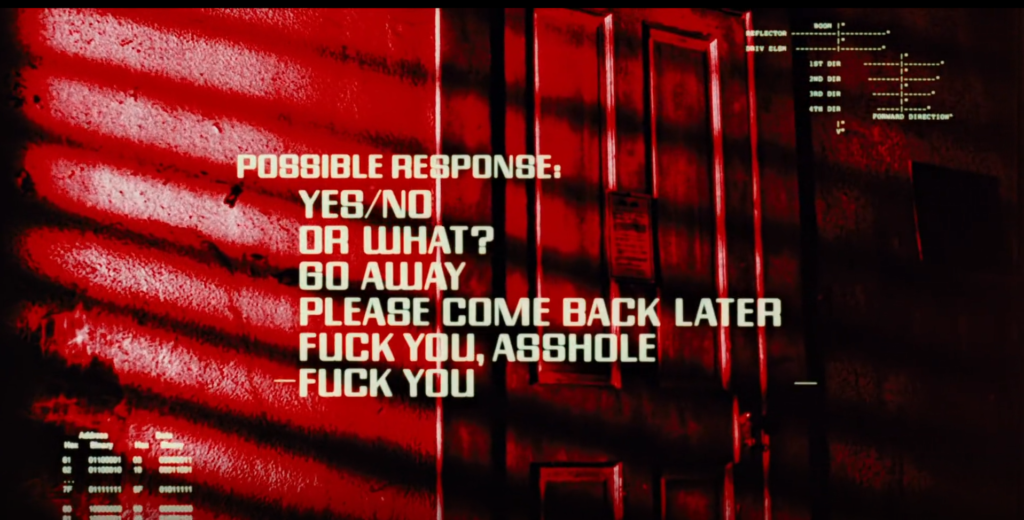

An aside: When you mentioned The Terminator, that’s exactly the scene I thought of. IIRC it’s the response options after the janitor of his flophouse asks Arnie, “What’s that smell, you got a dead cat in there?” The Terminator of course picks the reply that’s most offensive.

Because it is programmed for optimal communication with humans.

Honestly it isn’t something I think about that much. But I guess I would call my imagination a second visual field. It doesn’t overlap with my optical visual field. I can look at this screen and the text on it while picturing a cat’s eye in my heads. They are separate. One does not overlap the other. But my brain is really bad at multitasking so if what I’m imagining is particularly engaging, I won’t necessarily be all that aware of what I’m actually looking at.

Example. I had to stop listening to books on tape during my commute. I have what to me seems like a pretty vivid and detailed imagination, but I haven’t “seen” anyone else’s, so who knows? Anyway, I was listening with pretty keen engagement to whatever the book was. I can’t remember now. But what I DO remember is that all of a sudden I realized I was on the last leg of the trip home, and I had absolutely no memory at all of making the right turn where I had to switch freeways. I’d made the turn, but I remembered nothing. Basically, I’d been so busy imagining the scenes being read that it completely blocked my conscious awareness of driving. That scared me enough that I had to stop with books on tape.

Yes, this is what it’s like for me, the imaginary visuals are like a separate screen but you can’t pay attention to two things at the same time so sometimes you’re looking inwards rather than outwards, even with eyes open.

Ironically while I can visualize a character or a face it’s absolutely useless for me when drawing from memory, the two datasets are disconnected – I’ve developed a bit of a theory about the brain from that observation.

As for visual hallucinations, the ones I do have are from predictive processing, I often notice my brain trying to fit what it’s seeing before it fully resolves. You’ll be familiar with the experience of mistaking a bundle of clothes for a cat or some other animal (Do you still have raccoons?). One time I was bitten (Gummed on really) by a corn snake I was looking after and for a couple of weeks afterwards I kept seeing snake mouths in advertisement posters and the like (My inner mammal obviously was very impressed by the experience and kept a lookout for more snakes)

We do, in fact, still have raccoons, although the numbers have declined somewhat from the halcyon days pre-distemper die-off.

And yeah, the number of times I’ve mistaken an inanimate object for a cat is almost a source of embarrassment to me. (Although in my defense, our cats frequently do tend to just sort of lie there inanimatedly.)

A lot more people are now familiar with the equivalent auditory experience, thanks to the “Green Needle/Brainstorm” illusion going viral not that long ago (and there’s a more recent Barbie-themed version as well, no doubt whipped up to catch the movie’s hype wagon).

There’s also a now somewhat famous TED talk – a few years old now – by an Aussie pain prof, explaining pain perception in terms of nociceptor-interpretation pareidolia brought on by a rather more serious snake encounter.

During the pandemic, I started hearing ambulance sirens in the noise from the extractor fan in my bathroom. Almost certainly some proportion of them were real ambulance sirens, of which there were an excess at the time.

I’m an artist. Imagining images is my job. I still can’t “actually see” things I imagine.

Maybe that’s why you’re an artist: you need some alternate mode to experience/convey perceptions…

I’ve always thought my inability to manifest in my visual field something that I’m imagining goes a long way in explaining why I can’t draw for shit.

I’m somewhere around D in Paula’s categorization. I can’t really visualize anything. When I close my eyes, it’s just dark: blackness, or maybe a really dark version of static on a TV that isn’t tuned to a station. A friend who claims to do hypnosis was incredulous that I couldn’t form a mental image when he tried to demonstrate.

Any studies of aphantasia and hypnotism?

Oooh. None that I’m aware of. But that would be a cool path to follow.

This is such a weird one.

I don’t hear voices, I don’t see pictures in my head. At least I don’t think I do.

I can imagine an image though. Now that I think about it, it’s a bit more than that – I can imagine in 3D. If I am designing parts for a project I can see how things connect, how they fit into each other. What is inside them. Well, simple things at least.

I don’t see how this would work as an overlay.

It’s sort of like a computer. A computer does not need the monitor to understand (as they do) an object. It processes the object’s dimensions, placement, colour etc. That is how it works for me. If I think of a green cube perched on one of its corners, I don’t see it but I know it’s facets, position, colour etc.

Not that I am saying it’s like being a Mentat or something. Or maybe it is like being one, just with the processing power of a Commodore 64.

I think I read recently that people are split on whether they hear a voice in their mind/head when reading and those who do not. I can’t recall if there was any explanation or what effect it has on reading ability or desire to read. As I type this I can hear my voice in my head speaking the words.

At least two terms have been separately coined for this. One is anauralia. The other is a hell of a lot more awkward and difficult to remember, and probably doomed to a quick extinction.

The other one is anendophasia.

I still have a hard time wrapping my head around Aphantasia as a concept. I have always had a narrator/monlogogician running in my wetware, and almost as important and prevalent, a DJ. The fact that there are people out there who have neither, is heart breaking; that they miss out on the company and music with themselves and of themselves.

My long dark tea-time of the soul started when I finally realized that that voice was merely an echo of myself, and that there really was no one there. With that said, I would still prefer this heartbreak of discovery over never having that voice/song play in the first place.

I experience something similar and its torture. I suppose that it depends who your companion is. I need to have my head filled with nonsense (mainly games, and only those that manage to absorb me or searching for something concrete) or I’m constantly hearing music (repetitive fragments of which I need to find the source or I’m a wreck) or having detailed and repetitive debates with myself. Horrible debates about horrible things (tragedies, inadequacies, nihilistic views about reality…).

I tried to exorcise those by writing them, but then they, or my willingness to give them external form vanish

In fact, I begun to read Peter for the vampires, but I stayed for the

zombies. Such a blissful state…

!

Glad to be of service. However inadvertent…

Blobitt, that reminds me a lot of accounts of OCD. Not the wildly inaccurate pop-culture idea of it, but the version reported and described by people who have the diagnosed condition.

It also overlaps noticeably with accounts of ADHD and schizophrenia.

Findings concerning the neurological effects of methylphenidate might interest you!

I think a lot of these kind of questions require a couple of preliminary sessions just to agree on meaning and terminology.

I agree. But the thing that got me started was this excerpt from Justin Gregg’s If Nietzsche Were A Narwhal, and it stepped through the ambiguities enough to make me go whoa…

I do find the whole thing very interesting, I just fear that as “being on the spectrum” a couple years ago, social media tends to paint too glamorous a picture (haha) of anything that isn’t “neurotypical”, and open questions and polls will be skewed by people latching on anything that makes them feel different or special.

Checking on the picture here, I would consider myself a 2,5-3, and I have always thought I am at the absolute top of the Bell curve. Not having an “extremely vivid mental imagery” doesn’t mean you have aphantasia, just that you don’t have hyperphantasia.

Whilst you’re recalling the pitfalls of meaning and terminology, don’t forget to acknowledge how incredibly crude that pictorial scale is. Suitable for stone age psychology studies, no doubt; which is where we are now, but hopefully not for long.

The advantage of linguistic meaning and terminology is that you can triangulate. Take more readings, from more individuals, attempting to describe closely-related phenomena in different ways; and compare their phrasing to the context in which similar phrasing is found in a corpus of the natural language that the individuals are writing in. Look at the wealth of data points that you have, merely in the comments on this blog post!

Huh. Interesting.

If someone asked me to imagine a red star with five rays, I’d tell them I can do no such thing. I mean, I know what a star is, I know its properties, number of rays and such, and same goes with color, but actually imagine it, like see it with my mind’s eye? No way. Maybe it has something to do with synesthesia or that blasted visual snow syndrome that bothers me so much. Anyway, I hate it. It sucks to be an artist when you fail to imagine things you want to depict.

Thank you very much for your input on this.

Oh and there are people who say it is possible to train oneself to Literally See Imaginary Things. https://old.reddit.com/r/CureAphantasia/comments/16t8epu/image_streaming_20_how_to_image_stream_to_develop/

Huh. Maybe I should give that a shot.

As others have said, it’s not literally present in the visual field like a hallucination. It’s more akin to the visuals one has while dreaming.

There is a definite sense of “seeing” the thing, but it’s not particularly associated with the regular visual field.

It reminds me a little of software emulation. As if part of the brain is mimicking the experience of sight, but without use of the normal hardware, our output display.

Like playing a Nintendo game on your laptop. The brain is imagining what it is to have eyes that see, distinct from real ones.

We say “mind’s eye,” because to a degree it’s like an eye is opening inside the brain and “seeing” your imagination.

Yeah, except some people are saying it is literal. Check out the image in my response to guayec just upstream.

Some people say it is literal, but what do they think that means? What do they think that you mean when you ask them if it’s literal? How are they forced to simplify their own experience, when they try to describe it to you – and why?

You’ll need a lot more text than two pages of Gregg’s to get to the bottom of it.

I do not have a mental pop up display and I find this visual imagine-ary to be as weird as when people say they “think in a language”. Like there is some sentence being formed in their head when they think stuff mundane like “I feel hungry”. I think these things in an extreme abstract sense and the idea of strapping all the meaning into a single language’s words seems bonkers. I only go through the trouble to make words when I need to you know share my thoughts with other beings that presumably can understand (Sometime to cats which I am not so sure about). How do these people interpret words like “Cat”? language is so imperfect and inaccurate. are you talking about an animal or a large construction equipment company, which animal? You mean that Tiger over there? I can’t imagine how mundane it would be going through life stuck in the limits of language.

I am one of those poor, language bound souls. But not exclusively? It is hard to put into words. I feel like a lot of my thinking happens in an inner dialogue, and often there is a really smooth transition between this inner dialogue and communication with someone. Conceptual understanding of a lot of ideas works embeded into language for me. But when it is about body experiences (sports, dancing, sex, illness) or music (I was in a professional choir as a kid, so I’ve developed a lot of musical muscles), language takes the backseat completely.

Wait, what? That is what those studies meant with “Minds eye?” Because i sure as heck dont see actual images popping up in my visual field, except when i dream.

I was always convinced that was the “default”

By the definition in the post I am also aphantic, but it’s strange to learn that I’m supposed to be in the minority.

Explains some misunderstandings at least.

(I also see visuals in my dreams, but only “imagine” without an actual visual representation while awake. Then I am still able to describe and recall details, relations, configurations anything on the conceptual level works. It just isn’t a picture, or actual visual representation.)

Yeah, I don’t want to answer with a binary.

Visualizing detailed images does not come naturally to me but with concentration I am able to do it, sort of.

Visualizing abstract images is sometimes part of my creative process (in making software).

I am not the least surprised that this is a human characteristic where there is wide variability. While it’s maybe not surprising that a relatively impoverished visual inner life correlates with an ability to score more highly on tests of verbal skill, it might be interesting to see the correlations with other factors in how the mind relates to the world. I’m guessing that dismissing highly visual subjective experience as “pointless extra processing” is just ignorance talking.

If you’ve read our host’s most famous work, then perhaps you recall all the “pointless extra processing” that Sarasti engaged in, in order to parse data about Rorschach as an array of screaming faces?

Then again, that may be excusable as misdirection…

Off topic question for you Peter

Why do you describe sneak peaks of your writing as fiblets?

“let” meaning small thing (“tartlet”, “niblet”). “Fi” from fiction. “Fib” from lie (which all fiction is).

Fictional fibby Niblets. Fiblets.

Thank you for answering.

That may be the etymology though I can’t help but feel it’s inadequate or misleading somehow. I’ve always associated to lie with the intent to deceive, yet the very best fiction tells us ‘truths’ non-fiction cannot. Charlie Stross wrote on his blog recently that “he tells lies for a living” which I thought was amusing but not the whole story because he does so much more than that, what he does, what all writers do, is paint with words. Some more skillfully than others. Outside of a courtroom or under oath, is telling a fiction always lying? You guys build a piece of art word by word. One wouldn’t say a painter, a sculptor or a musician lies for a living. Just different mediums. But all have in common the purpose to entertain, to delight. And in fact when you get right down to it you/writers are able to flip the curtain and say “do you really want to know what you are?” Here’s the truth.

I did consider “ficlet” for a while, but it just didn’t resonate. Also it made me think of teeth.

I have always had a pretty active imagination. When I was very young, this manifested in the form of “stories”, sequences of events that I would generate and then get my friends to help me act out on the playground. Generally, we’d all go fight on an alien planet, explore an ancient temple, or something else along those lines. Not too different from most forms of childhood fun, as far as I’m aware. However, as I grew older (around age 7-10), I learned that I could take the same conscious phenomena which I had previously translated into impromptu schoolyard dramaturgy and use them to produce things like art and writing. Over the years, as I developed both my skill with drawing and prose, my primary interest was realizing things I imagined.

I hardly ever draw or write about subjects that are not imaginary, unless I am intentionally trying to exercise and improve my skills in either medium. People who have seen my artwork of other planets, spacecraft, aliens, and the like usually describe it as “vivid”. People who read my writing about the same subjects tend to call it “cinematic” and tell me that they feel as though they can actually see the action and places described.

Here’s the thing: I can’t. I see nothing. I have no strong mental images in my typical, sober consciousness, even when I am actively using my imagination. Interestingly though, I actually have experienced vivid mental imagery— I just had to take LSD to do it. The qualia I experienced during the few acid trips I’ve taken were never quite on the level of genuine visual perception, but they were extremely detailed “pictures” that I could “see” inside my mind. In comparison, the things that serve as the basis for my pictures and stories are woefully indistinct. They’re vague ideas of sequential events, sensations of movement, collections of emotions, maybe arrangements of objects or characteristics. The thing which they never are is coherent and vivid pictures. In fact, no idea really becomes coherent for me until I start working on it. When I’m drawing, I often begin a piece with a series of random (to my conscious knowledge, at least) strokes of a pencil or pen, from which I then proceed to construct a sensible piece of art.

Perhaps interestingly to you, during the act of drawing I find myself completely dissociated from my hands. A few years ago while I was working on a highly complex piece, I became aware that I was simply observing my hand working. I was so detached from what it was doing that I was able to conduct a very informal observational study of how it moved. I determined that while hatching (shading by putting down a bunch of small straight lines next one another, if you aren’t familiar), my hand wasn’t moving the pen in discrete linear movements, but rather in a very tight ellipse. To create the shading lines, my fingers would simply bring the pen tip in contact with the paper for some fraction of a second, then lift it back up to stop. Not a particularly earth-shattering observation, but certainly strange that I was capable of making it without disrupting the unconscious act of drawing in the slightest.

Getting back to the topic at hand, I think that I am something of a counterexample to your idea that people might have a hard time understanding your prose because of your lack of mental imagery. Given that people appear to “see” my prose despite a similar visualization deficiency on my end, there’s probably another confounding factor at play. If I may be ridiculously presumptuous, I’d say the biggest issue I noticed on a recent re-read of Echopraxia was the misuse of figurative language.

Don’t get me wrong, figurative language is great, I love it to death, and you’re good at writing it. That said, its easy to get tripped up if you aren’t being mindful of its two primary uses: namely, making something familiar strange, or making something strange familiar. In literary fiction, figurative language almost demands to be used for the former of these purposes. Likewise, science fiction requires the latter. The sort of beautiful defamiliarization you get from the dense, hyper-metaphorical prose in a book like Blood Meridian plays great when your subject is a desert, which everybody understands on some basic level. On the other hand, it does not work at all when you’re describing a super-advanced spaceship and also throwing in tons of technical jargon on the side. Maybe something to keep in mind, maybe something to ignore. Either way, this post has grown far too long, and I must now get back to other things.

That’s a really interesting insight into figurative language. (And the Blood Meridian reference really resonates). I will keep it in mind.

Suppose, T-800 was built with microservices architecture where different parts of the system exchange information via JSON.

Here we can see the JSON dumped into console (on the screen). That means that developers haven’t switched off the debug mode.

Built on ROS Robot Operating System – Wikipedia

Nodes publish and subscribe to topics. “topic_snarky_reply”

Which given the devs were incinerated with by nukes by Skynet you can forgive them for not having done so.

If I concentrate of thinking about a racoon I bring to mind the concept in little bits (washing hands, cute scavenger, trash, etc.). If I try to visualize my mind brings the concept first and if I really concentrate I can bring to mind (to a different place that my visual field) tiny visual aspects (general form and color, its eyes, its hands in a bowl of kibble).

Admittely, my mind and memory works in abnormal ways. There are things that people notice as a matter of fact that elude me, and I perceive things lost to those that surround me. My therapist says it’s hyperattention, but I’m not so sure, because the same thing applies to my memory. I struggle, as an adult, to remember the names of months, but I can create synopses of books or inane conversations I had decades ago. I remember minute facts like the name and habits of different birds, or pieces of history, but any date or series of numbers or the names of colors (beyond the basic palette, of course) is lost to me, and I need cheat sheets to go through the day white I prattle absently about random factoids or argue with myself.

As you noticed fairly, using the literal image on your retina would actually be too computationally heavy, inefficient and useless (and even impossible AFAIK because retina itself is a computational unit that pre-processes image completely independently before sending it to the brain). So I assume that image integration process can happen at any upper layers of your perception. Same way goes with sound input, btw, but it’s even more tight, there are quite a few of people like me who don’t need an mp3 player to listen to their own music, unless they are otherwise distracted.

It goes deeper after that though. I’ve spent most of my life clutching a mouse playing FPS games (and recently VR games too) and I have trained spacial imagination, so I can build detailed maps in my head and navigate them very fast, I can imagine lines of sight and direction of movement of objects without even thinking about it. It does however take lot of concentration, effort and curiosity to go beyond basic things.

The difference between seeing things and not seeing them is the difference of using different inputs/outputs on your PC – you can use virtual devices that are sourced from inside the PC itself to avoid certain hardware limitations. I.e. some people need to close their eyes to cut off outside interference. Some people need to say the word “apple” in their internal voice to concentrate on the image of an apple or think about it. Some people like me can have internal “engram” of an object for quick reference that doesn’t even need to be named in any languages (I’m pretty sure it functions like internal language to reference to corresponding neuron clusters in my head). Oftentimes when I am day dreaming, parts of my senses literally black out to not bother the imagination.

However, this measure of powerful imagination needs some sort of restraining mechanism that will literally diverge reality from the imagination, and separate facts from fiction. That is the reason I do not believe in any supernatural things like ghosts and aliens walking among us, because I know how deceptive the basic human perception, reasoning and memory is (hell, I use it all the time to be more like people around me). I literally know when my own mind feeds me it’s input, because it’s alwasy a messy garbage.

I think people of the past didn’t have very much experience with interfacing like that, 640 kB, TV news and all. They didn’t have access to 12 GB neural nets and 4K screens. T-800 is now obsolete, mass produced model. I can’t think how different would the reality look like for people who used to have modern computers since like 4 instead of 14-16 like me. I hope they can do well enough.

When my eyes are open I think I can see vivid images with my imagination, but once my eyes are closed, I can barely “see” simple geometric shapes like a triangle at best. And even that’s may not be real, sometimes it feels like I’m trying too hard to visualize and just overfitting the noise I see when I close my eyes. I can imagine something to a fair degree of detail, and “recall” those details while describing them consistently. But, no, I can’t see this imagined thing in the same way that I see the world with my eyes open.

Then after talking about this in depth with my BUG we discovered that she could visualize imagined content vividly, whereas the limit of what I can do is some simple, monochromatic outlines, with my eyes closing and concentration. She was surprised at my lack of this ability, stating that a lot of the time she writes fiction almost by first seeing what’s going on in a scene, and then writing what she sees. It’s not exactly binary; if you use the scale of this picture as a reference, she describes herself as a 1, and I’m basically a 4.

wait. what??

I’m just as shocked as you, I assumed the mind’s eye was something separate from the visual field, that hallucinations were the realm of altered state of consciousness due to drugs or other things.

A “bug”, not a feature.

(a side note: i have tried psychedelics more than a few times, and 9 times out of ten, no visual hallucinations outside my mind, most i ever got was some fractal patterns in the dark, but never stuff that made me doubt my visual field, maybe that’s related)

But this..this might explain a LOT of crazy stuff from history.

A guy saw a bush take fire and speak to him, for one.

like, if self induced hallucination capability is the norm, and the subconscious is actually in charge, then manipulating people, especially through religious means, makes you able to bend their brains to LITERALLY see what you see!

It makes being unreasonable much more reasonably undertandable.

The Earth is flat not because i’m pretending in my mind that it is, but because I literally see it that way, all the proof is invisible to me because my brain shows me what it wants, and is capable of altering the signals i receive.

It might make sense but the notion of it is…terrifying, at best.

An anecdote (related by someone on reddit).

To summarise; a relative who was a gymnast was on a beach, amusing some kids by jumping in place and doing somersaults in the air. A much older couple came along, and the male was stumped at what the kids were so entranced by. Apparently, all that he could see was the gymnast jumping up and down on the spot.

Stuff which is completely outside your experience, and outside what you can conceive of in your beliefs about the world…? You just might not even see it, not even when it’s right in front of you.

Then again, perhaps anecdotes like that are dataset-poisoning attacks?

There are some people in tulpa-forcing communities that claim that they induce literal HUDs over video feed from the eyes.

Hi, everyone.

I’ll go somewhat side-topic and share my audio perceptions.

Fact 1.

I spend some time in server rooms, where it’s noisy. May be a whole work day.

Fact 2. I write some electronic music as a hobby.

Fact 3. Usually after being long exposed to noisy environment, I actually start hearing things, that are not there. Nothing scary. Sort of a pareidolia. Like simple melodies emerging from the actual noise. Not invasive, controlable, follows my imagination. Vanishes in a few hours.

Seems like some brain module becoming hyper-active due to overflow.

I have had very similar experiences. The effects of tetrahydrocannabinol especially made it “pop”, even to the point of often hearing extra music within other music that I was actually listening to (extra instruments and instrumentation, accompanying melodies, etc). I also have been through periods of getting something like this phenomena during hypnopompia, but with no need for any stoner drugs, and seemingly with a lower requirement for ambient noise to amplify. It would happen if I had been listening to a lot of music recently – and the style of the music that my bored brain module was composing would be heavily influenced by the type of music that I had been listening to.

In both cases, I often got fairly complicated melodies. I managed to actually work a small number of them out – as in figure out how to play them on a nearby instrument, or put them into a midi editor – and it turned out that they were quite good, or at least that they appealed a lot to me. Unfortunately I never had the skill set to produce them to a sufficient quality that anyone else would want to listen to them.

I also get a linguistic version during hypnogogia. Disconnected sentence fragments form in my “inner monologue”, independently of my executive volition, as the alpha waves disrupt the beta waves. Entire sentences also form which are meaningless, but follow the correct rhythms and loose sentence structures for English. Apparently this is not an uncommon experience – I noticed that Dylan Thomas mentioned having it in some of his works.

My 70 yr old friend has recently had to have an eye removed. He has lived in the same house for 40 yrs. with his good eye closed, he “sees” his living room, complete with 2 cats which move about, in great detail. Memory, I suppose. It will gradually fade.

I see things, but not in my visual field. I’ve got an extra visual channel that imagined things show up in.So they don’t cover up the stuff in the real world. It covers an oval, about 45 degrees wide and 30 degrees high. That’s less than half of my actual visual field, so I can’t visualize really wide stuff like a sunset.

That’s really weird. You’ve got me trying to imagine where that little oval sits, relative to your direct visual field.

I literally see an image, but not ‘in’ my visual field — it’s not picture-in-picture, overlaying anything, more like a second monitor i can switch attention to.

I sort of flip back and forth between two windows: day-dream mode (where I spend most of my time, I’m sure) and real-life mode. They aren’t overlayed. I didn’t realize the lack of an overlay made it aphantasia; I thought people with aphantasia just lacked the day-dream mode.

There’s this manga called Shigurui, by Takayuki Yamaguchi. The samurai in the story all have over-active imaginations, and constantly visualize each other as animals, such as tigers, snakes, frogs, dragons, etc. I was under the impression that was an anime thing though and not something most people really experience.

I wonder if there’s a cultural component to this? Could it be the case that first-worlders and people that spend all their time on computers are more likely to have aphantasia, while while third-worlders and people that mentally reside within the natural world are more likely to experience these kinds of vivid hallucinations? If so, I question ther assertion that these mental Terminator HUD’s are computationally inefficient.If humans living in the wild can literally hallucinate images of wolves or praying mantises over their visual field on top of their images of people, there must be some kind of adaptive value to it.

Like most people I’m somewhere in the middle, arguably able to or not, depending on what you describe as ‘visual field.’ But just to add to the confusion…

Since I was a teenager I’ve effectively only had one working eye. The other one’s extremely blurry (originally a cataract, removed and had a cornea transplant to try to correct it, but it was never very successful). I can make out vague shapes and colors, maybe tell a person was right in front of me but not identify their face. And,very quickly, I found that I mostly… just edited out the view from that eye from my perceptions. Literally the center of my viewpoint is the middle of my good eye. My other eye, though usually open, is effectively extended peripheral vision on one side. If I move something only in the view of that eye, I ‘sense’ it’ but it’s a little like a vague fluttering ‘somewhere else’ than a part of my visual field. However, if I close my good eye, suddenly my bad eye becomes all my visual field, it’s extremely low-grade but it’s THERE, just seamlessly shifting into place as ‘primary’ (a bit like I teleported a few cm to the side into a nearly identical blur-world).

Imagining is a bit like that, for me. Most of the time, if I picture something, I get a vague fluttering that I sense somewhere in the peripheral of my mind, not blocking my vision, that gives me a sense for the shape and details I’m after. It’s ‘somewhere else’ but is it visual? I don’t know, honestly. But if I really decide to entirely focus on it (and yes, closing my eyes helps), I can get something which approaches a visual image snapping into into primary. It usually takes a lot of mental effort and often the details shift from moment to moment. (Sometimes if I’m very close to sleep it’s easy and vivid, but I’m definitely still conscious) But like my bad eye, even though this additional display becomes briefly primary, it’s still somewhere ‘else’ than my good eye–or my bad eye–and when it’s not primary, that input is still there, processed on some level, just not intruding.

I can relate to this. I have a lazy eye, which is myopic, so I basically do not use it while looking at the objects far away. It does, however, provide this extended peripheral vision, so I kinda have an illusion that I’m seeing normally.

Honestly, this is one of the reasons why I like the hypothesis that we don’t see stuff but rather construct a mental model and update it using visual input. It really feels like I’m imagining the lazy eye visual field rather than actually perceiving it.

With The Terminator, I liked to imagine the HUD was a legacy output from very early in the lineage of the machine’s OS when it was still intended that humans would sometimes operate or monitor the defence system. The inefficiency of generating a HUD wasn’t significant enough for Skynet to bother patching it out and any selection pressure was not great enough to weed it out naturally. Of course there’s nobody around to see this output… except the audience.

Agree. The overlays are the kind of code that developers add when they need to demo the new system to the people who have the money.

This is an excellent retcon.

Uhhhhh guys, you’re making me feel like a time-traveler: There is no such thing as ‘literally see’ …anything.

If you can see colours at all, you are hallucinating things which are not there. The existence of optical illusions gives us some sense of the extent to which perception is the product of what Helmholtz called ‘unconscious inference,’ or something to that effect in german.

Here’s an illuminating lecture that Anil Seth gave somewhere as provincial as Belfast, if you’re not already familiar with these ideas:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vayfDg4QpJ8

But I thought everyone knew this by now, or maybe I’ve got the year wrong.

Oh Tom, you pedant.

Of course there’s such a thing as “literally seeing”: it’s the act of conscious visual perception. The fact that our entire perception of reality is artefactual is beside the point. It’s a hallucination, but it’s still a hallucination that is literally perceived visually.

The twist here is, it turns out that some of us hallucinate across more screens than others.

Pedantry is fun, but that wasn’t my main motivation; in this case it’s more that aphantasia is even weirder if the things that people routinely see are hallucinations anyway.

I would frame the question as: ‘does your visual imagination obscure part of your visual field’ or, ‘when you remember a scene or object, is it something that might be mistaken for something currently happening?’

For myself, I do rely on picturing things in my head to remember anything, but I think I probably have less imagination than most people. So the survey question in the post makes no sense to me.

No, wait, should’ve said: if I’m thinking of something, I can’t really see what’s in front of my eyes, because my visual attention is busy with something else.

Feels like I’m spamming the comments, and I don’t expect anyone to have time to watch videos, but people who enjoyed Blindsight might be interested to know that Thomas Metzinger has a new book coming out this year, and it’ll be available open access from MIT Press Direct:

https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262547109/the-elephant-and-the-blind/

And if you do like videos, here is Metzinger chatting about minimal selfhood and active inference with Karl Friston, who might be familiar to readers of this blog from Mark Solms’ book, if nowhere else:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qlPHGnChhI4

(over two hours; not worth it)

My history with imaginary visuals is kind of interesting. As a child I could vividly imagine what something would look like with a detailed enough description and a handle on the meaning of the words used. I could imagine things that weren’t there which I used to play with. It came in like an overlay, colour-coded to mismatch the real environment so as to avoid getting run over by a truck.

Over time I have realised a few things – it is energy intensive, I am using a lot of processing power. It is very useful, because I can use it to solve difficult topological problems and even some math problems if the wording isn’t too abstract.I can measure things in space, useful for moving furniture, packing items into a limited space, fitting objects through a doorway, etc. I can imagine invisible topologies, such as invisible eyes and avoid tripping them, camera’s field-of-view and avoid or center myself in them, understand where in a given room blindspots are likely to occur and position myself accordingly.

I do have ADHD and some qualities that might reveal some form of Autism (or just normal trauma intensified by the ADHD) which may have an impact on this. Certainly the focus required was a plus since it would occupy my attention for an extended period of time and thus stave off boredom.

If I understand the concept in discussion correctly, I fall somewhere in between, like most people (boring). I can get only vague pictures and only inside my head, not in the actual visual field. When I’m reading books I usually parse the descriptions as abstract concepts, without visualization (I still can visualize if I try, but the results is pale and usually not worth the effort). I guess that can partially explain why I am reading faster then my peers.

But the topic reminded me of something that can add another layer: a particular effect I had while tripping on DXM, that I haven’t seen described anywhere (and now I’m getting the idea why). Actually, what makes it more interesting, it was not during the trip itself but rather at the comedown, when the mind is already pretty sober. Closing the eyes, I saw visions of things and spaces in extreme details. Like, actually more detailed then reality — in fact, this is how I was determining if I have my eyes opened or closed: the state with worse visual fidelity is reality. This was somewhat under conscious control but not very firm, so I can’t say I visualised stuff, rather then it visualised itself.

Don’t know, what to make out of it. Seems like there is something in the brain that actually controls the imagination power and it can be manipulated.

That actually tracks with some of the stuff I experienced on my one and only acid trip. As for the clarity of imagined/perceived objects: that is, apparently, a thing (based on some of Metzinger’s stuff that I’ve read. There are apparently geometrical forms built into the wetware (“form constants“) that look “realler than real” because they manifest upstream of the retinas, and are therefore not limited by retinal pixel rez. It is very cool.

Are you a Porcupine Tree fan?

Judging by their wikipedia entry, form constants look rather like edge detection as performed by convolutional neural networks with various different input field symmetries, and with their outputs jammed to “on”.

I suspect that what you’re looking at there may be equivalent to the decision hyperplanes from edge detection in some mid-layer of your visual perception, with the kaleidoscopic effects resulting from the specific chain of boolean combinations used upstream when flattening them to the dimensionality of your visual field (as presented to your reflective cognition).

Oh, I hope the day comes when I get to read this guy’s writings, from what I get, he tackles some seriously mind-blowing stuff.

I am! Do you like them?

I do!

I mean, not their ambient stuff. I don’t see the point of that at all. But pieces like “Mellotron Scratch” and “Sever” and “Trains” and “Piano Lessons” give me a reason to live (and “Radioactive Toy” has certainly acquired a recent currency we all hoped wouldn’t ever be A Thing again). What I’ve heard of the new album rocks. And Wilson’s remixing work on Tull’s backlist has uncovered a few revelations, too.

Gives me a little hope in a world where everyone else seems to think that Taylor Swift is the apotheosis of musical creativity.

Cool! PT were basically my gateway to prog so I cherish them a lot, even though don’t listen to them so much anymore.

Yeah, Radioactive Toy hits differently these days…

OK, but that’s not half as entertaining as what this guy reported: https://www.reddit.com/r/DMT/comments/mwuvpv/anyone_else_getting_amazon_ads_when_breaking/

And not nearly as cool as self-transforming machine elves!

Lol, the horror.

Love this bit, I really want someone to incorporate it into a dystopian novel (but we live in it).

Well said.

Reading through all of this has made me acutely aware that I have definite proprioception about where my imaginary visual field is located!

When I have my eyes open and simultaneously imagine an apple, and then query my proprioception as to where that apple is, it consistently tells me that it is about eight inches up and an inch or two foreward of my eyes.

Out of my actual physical field of view, but nevertheless consistently *there*.

Does anyone else have a consistent proprioception of where their imaginary object is? Is it the same as mine? Above and slightly forward of your eyes?

For me, it’s behind my eyes, almost directly. But it’s also accessed through a “window” that opens into a different space. The window is behind my eyes, the apple is in the other space.

Descriptions from some of the other people who have commented here sound to me as though they feel that it’s behind their eyes as well, or in the middle of their physical head.

I blame that crappy wikipedia diagram for everyone independently choosing apples (except for the ones who saw Twitter Guy first, and chose sticker-stars).

This is extremely interesting. Are you phantasic to any degree? That is, are there any objects that you CAN visualize in your field-of-view, whether eyes open or closed? Or are you aphantasic?

I myself am aphantasic, so I can’t truly visualize, say, an apple, and though I’ve never before thought to query my proprioception regarding such phantom apples, trying to do so now yields nothing noteworthy.

Your experience reminds me of something I read about time-space synesthesia. That some people experience (perhaps “feel” is a more appropriate word?) days of the year as existing out in space around them, perhaps in a (counter)clockwise ring around their bodies, perhaps as the current date residing inside them while the previous and next reside behind and in front of them, etc.

Do different imagined (or visualized) objects reside in different locations for you? Do they ever exist, regardless of their visibility, within your visual field?

Apparently, mass linguistically-induced time-space synesthesia is a thing.

Here’s a talk that describes one recorded instance of it. (“How language shapes the way we think | Lera Boroditsky”)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RKK7wGAYP6k

One would assume such vivid types of imagination and practical manifestations of cognitive schemas to have been selected out for the gen pop beyond general abstraction. Or perhaps for certain outliers with robust powers at imagery, the trait being accompanied by a mental “gate” of sorts, to be toggled on/off at will during times conducive as well as reinforcing of creativity and entertainment.

I often wonder how some of us with attention-deficits and slower reaction times would fair if society were to dissolve back to the caveman ethics/rules. The price we pay for generally better odds at survival under the normal curve is to be surrounded by folks who lack perspective and can only see just past their noses. Not to mention uninspired and inane world leadership failing miserably at the challenges of today: hence, why we all here are scared shitless of tomorrow in unison with Peter the Great!

So let’s literally conjure the most realistic image possible of a silly clown’s nose and party hat on the very hungry lion that just cornered you in the wild. Or picture your (please insert 2024 political candidate of choice) with similar circus apparel. Eliciting laughter upon one’s impending demise mitigates some of the drama of the carnage.

Anyway, abnormal psychology and the current psychiatric establishment also pathologizes hallucinations (i.e., false perceptions) as diagnostic of Schizophrenia-spectrum disorders or as products of intoxication from various mind-altering substances. Same for flashbacks or derealization in trauma-related disorders. These are literally “breaks” from objective reality (as the base social convention), disrupting behavior to the degree of sometimes posing imminent threat and danger that typically calls for intervention in order to protect self/others and manage grave disability.

That said, I wonder if multi-layered visualizations (alongside simultaneous processing of more than one auditory and tactile perception at a given time) with an augmented format much like the semi-transparent T-800 HUD template would present certain advantages. Given this fancy Apple vision tech that just released for the masses and the projected (pun intended) scope, superimposing a parallel reality over the base one allows for higher-order processing and mental computations that will boost the creativity and entertainment factor noted above. Probably improved emotional and psychosocial experiences are to be expected as well.

And to answer the original query posed, i can picture the faces of my loved ones in front of the screen as I’m typing this although nowhere near in detail of a photo or (soon) virtual reality facial scan. I mean even the dead will come back to life quite literally! Gonna get interesting and very weird. Not much longer now. Buckle up!

You’re missing at least one option.

“It’s a spectrum, dependent on how hard and long that I concentrate. It starts at imagining without ‘imagery’, instead feeling more like a loose bundle of raw associations. From there it progresses towards ‘picture-in-picture’, and where it caps out depends on how hyperphantasic the individual.”

In this individual’s case, I’d guess it to be a bit north of median hyperphantasic. Perhaps as much as 1 SD.

Also, “no conscious awareness of visual inputs” is a very hard sell for being the same thing as “philosophical zombie”. Even one of the stretchiest words in the English language balks at stretching that far. Didn’t you write a whole book trying to work your way through linguistic confusion about that…?

OK, well, first, yeah: I didn’t craft the most nuanced poll here, for sure. But you have to remember I wasn’t especially interested in nuance: to me, the idea that pic-in-pic happened anywhere, to anyone, under any circumstances kinda blew my mind. All I wanted was to know if the folks here ever experienced anything like that at all. Binary’s fine for that; I can take on the the gradations later if i want, once I’ve been convinced of the basic existence of the phenomenon.

And second, like, you do know I only threw the p-zombie option up there for a laugh, right? (Although there probably is a parallel timeline where I applied a bit more rigor to the joke).

OK, you got me over Poe with that joke! I noticed that it was a joke, but I didn’t get as far as noticing that your conflation of blindsight with p-zombieism was intended to be the punch line.

A number of people in the comments have tried to describe the idea of having a visual image (of lesser or greater fidelity) in their head, feeling like it’s located somewhere inside their head, without it actually being in their visual field. That matches my own experience well enough, with the additional wrinkle that I wouldn’t call it visual at all.

“Picturing” an object in this way – I’m doing it with an apple as I write this – feels like recalling the conceptual model of apple that I’ve previously constructed from seeing (and touching, and tasting) a lot of different apples from a lot of different angles.

Imagine a character editor in a role playing game – you know, one of those ones where you have all the sliders for controlling your virtual hominid’s hair colour, how long their nose is, how close their eyes are together, etc. It’s like that, but the sliders are moved instinctively, like moving a limb. One slider changes the variety of apple, another zooms in on a part of the skin and changes the texture. And so forth. By patching in some concepts from elsewhere in my experience I can make a blue apple with pink spots that tastes like cheese. However, it doesn’t and can never have the raw sensory immediacy of a real apple – because I can’t feed these associations back into the sensory pipelines from the beginning. Not without the aid of a 3D printer and a lot of effortful preparation, anyway.

Imagine an AI art generator, short-circuited to output the hallucination prior to it being flattened to a discrete 2D array of colours. It retains a lot of extra variables… but depending on what you want to do with it next, you may have to shear off most of that surplus information. High-dimensional square pegs into low-dimensional round holes do go, but not entire. And reflective cognition is so goddamn expensive that it can only handle a miserable four dimensions while retaining a playable frame rate.

Which brings me to dreams. I’m fairly sure that I don’t get those in my visual field, either. Those also happen in the prefrontal synthesis space, where the conceptual apple materialises. While dreaming, I may imagine that I’m seeing a visual field – some part of my fitting brain may decide those are the best terms for interpretation. But it doesn’t feel like the feed from my eyeballs while awake (and as I’m sure we all know, that feed is largely fantasy as well, even though it feels like a raw camera feed on the back of your eyeballs).

… and finally, Unreliable Narrator contamination disclaimers. I have a little bit of an AI-theory-geek bent. I didn’t always, of course; and as far as I can remember, my inner experiences throughout life have never deviated from something that would be reasonably described by what I’ve written above. For what value fickle memory may have, especially when grated through a crude morpheme filter.

This is fascinating. Your first couple of paragraphs map closely onto my own experiences. The last couple are alien to me. I can’t imagine a dream without a directly perceived visual element. It would be like lying with my eyes closed, seeing nothing but swirling darkness while I conceptualized an apple from memory. Which to me, doesn’t seem like a dream at all.

Also, I can’t imagine getting horny in my sleep without the visuals.

Your paragraph on Dreams stood out to me.

I’m aphantasic but I absolutely have visual dreams…

Ahh, but do I?

How could I ever be sure, seeing as my recalled dreams are always just that, recalled?

If my attempts to visualize an apple right now while I’m awake don’t result in me SEEING an apple, but rather me merely “rendering” it in (what I believe you are referring to as) the Prefrontal Synthesis Space, then surely all of my dreams recalled after the fact will also be such renderings, rather than visual replays.

And indeed this IS what it feels like when I recall my dreams, the memories of my dreams are not visual. Yes, I can feel-remember the spacial location of objects in the dreamscape, I can remember the chronology of events, but I can’t SEE anything.

So why am I so insistent that my dreams, in the moment of their happening, ARE visual? That I was actually seeing stuff rather than just waking up hours later thinking that I had seen stuff?

Well… because I’ve had Lucid Dreams. I’ve consciously experienced, in real-time, the dream (and its visual nature), rather than merely recalling it later (in its necessarily NONvisual form).

And now, rather than go off on a tangent, I’d just say that lucid dreams might be a particularly useful avenue of inquiry for anyone (phantasic or not) wondering “do I actually SEE in my dreams??”

Just cultivate them and find out for yourself…

And it occurs to me now, that although I may experience lucid dreams in real-time, my recounting of them is always necessarily after the fact, so how can I be sure that my lucid dreams are genuinely visual rather than fallaciously recalled as such?

Well, that’s something I can’t answer other than to say that the recalled “visualness” of my dreams & lucid dreams feels analogous to the recalled “visualness” of my waking experience 10 minutes ago when I started typing this response, and the waking experience 10 minutes before that, ad infinitum.

And, presumably, all those previous waking experiences, despite my inability to actually recall their visual components now, ought feel the same as the current waking experience I am having as I type this.

And, I must say, my current experience most definitely seems to have a truly visual component… or at least that’s how I remember it…

Interesting point about the terimator HUD. I think I agree with the other commenters that maybe direct imagination-vision overlay over visual field is likely something like Hyperphantasia?

It has made me wonder if intuitions about a HUD being computationally ineffective are totaly correct, for reasons cropping up in the comments: our brains (seemingly) weirdly bother to construct a consistent hallucination of our impression of reality around us all the time … so it looks like presenting to ourselves constructed information is quite worthwhile for intelligences ?

I have image & 3d shape, and auditory internal world, but not overlaid over my actual vision or hearing. I also don’t really have access to internal taste or smell, or much access to imagining touch or movement. My internal “minds eye / ear” is like a phantom version of those external senses, somewhere behind my eyes

Last thought: maybe Terminators have no internal experience of thought (as we all seem to have these minds eye/ear spaces behind our eyes) but instead “thoughts” are directly generated (by one model) as options over their visual feed for high level discerning by another model, and then said or vetoed. So the HUD is really ideas occurring to the terminator. Maybe overall this is slower and a bit more narrow, but perfectly effective for less complex agents? In the films terminators seem to take some time to process new information and ideas: maybe because they have to iterate through menu options through their visual field? I wonder if maybe many animals might be more like this: maybe having complex action selection occurring to them in their visual/auditory/chemo-sensing fields but maybe less or no “internal thought” compared to us (this is just a guess, obviously I have no idea what animals internal lives are actually like, but I’ve read many animals have less access to episodic memory, and it seems only us and maybe a few others have access to language or anything similarish to it) Perhaps that might be a way of simplifying an agent that still needs to pass as a human? This also suggests terminators are conscious (otherwise who is reading the text field in the HuD etc), just less conscious than us in some ways?

Peter, I love you man

I love you for giving us the best sci-fi that ever existed (Blindsight and its brother)

And I hate you for not following it up with more

I’m having vicious withdrawals

I want more of that universe

I want more too. I’ve been working on it. I would love to devote more time to Omniscience, but right now I’m making significantly more on screenplay and videogame work than Tor would be likely to offer even if they were beating a path to my door (which they’re, you know, not). And I got bills to pay.

Good whisky has to sit in a cask for a while.

Asking whether imagination involves forming a literal mental picture seems like a weirdly subjective qualia distinction. Is anyone imagining things by generating/piping 2d image data into first layer visual cortex neurons. There’s probably a more abstract latent space that efficiently encodes what/where data or equivalents for other senses.

Here’s a literal thought experiment. Imagine looking at a grey cube. Someone with a mind’s eye will see at most three out of the six faces. Now imagine the hidden faces change color. I think even people with a very strong exclusive mind’s eye view will perceive the change the same way they track when someone moves out of sight past a corner. Object permanence in developmental psychology might just be adding hidden variables to the representation in the pursuit of lower prediction error.

An easier test might be to imagine a person walking behind you or behind a wall or obstruction so they’re not visible. People feel/predict the person’s presence in their internal world model (at least I do).

Further questions:

– are some people simulating object permanence consciously having no hidden model state?

– are some people vampires?

– representing multiple possible conflicting world states

– the necker cube can be in both orientations quantum computer style

My guess is that it depends, mostly on practice and training data.

– Someone playing a lot of hidden information strategy games might have a vampire-like representation

– 3d modelling/design develops ability to represent an object as a 3d model with all features.

Likely not exclusive to humans, a fox hunting a rabbit might, when the rabbit disappears from view, feel/perceive/predict multiple paths the rabbit could take.

The failure to account for object permanence is interesting culturally and historically. The Aztecs believed they had to feed the sun god Huitzilopochtli with human hearts and blood to ensure the sun returned. It was a matter of survival to them. Object permanence is a good thing. Makes life predictable. Now if I could just get rid of the gremlins who keep hiding my socks.

What an unexpected treat it is to’ve stumbled upon this particular blog post when I merely intended to drudge up ZeroS for a leisurely re-read.

Of course, perusing this site led to a re-read of some WestHem Alliance Propoganda, and next thing I know I’ve fallen down a hole into the blog where I see the word “Terminator” in the side banner (which I obviously can’t not click on) and now, here I am, discovering that Peter Watts has aphantasia too!

It took me over 3 decades to learn what aphantasia is, that is, it took this long to realize that when most people say “visualize such-and-such”, or “I see objectX in my head”, they mean to VISUALIZE such-and-such and to SEE objectX. As in, literally (in the literal sense of literally, rather than its oft used figurative sense) see and visualize.

Previously I’d always thought those to be metaphors of a sort. Oh sure, I can “see” this thing in my mind’s eye. Yes, yes, I am “visualizing” this task. But clearly those words just mean to IMAGINE something, right? Surely people aren’t really seeing these objects of their imagination. Right?

Well it seems that some (or rather, most, if the stats are to be believed) CAN, in fact, SEE the contents of their heads.

What a shocker that was.

But then how could you know for sure? Surely you can’t devise an objective test for this, right? It all comes down to my interpretation of what it means to “visualize” or “to see” something. Right?

Reminds me of that expression, the one about the futility of comparing subjective experience. Something along the lines of, “how do I know that the green that I see is the same as the green that you see?”

How are we to know that what you mean by “imagine” or “visualize” or “see” actually maps 1-to-1 onto what I mean by those words? Well, as I was asking this same thing, years ago, I came across the following:

https://aphantasia.com/article/science/binocular-rivalry/

I encourage everyone to read it, but, In a nutshell, the phenomenon of binocular rivalry can be used to give some pretty convincing evidence that aphantasia is a real thing. That is, it’s a real thing in a way that goes beyond people simply defining their perhaps-totally–subjectively-different experiences as congruent.

Show someone a card with a doubled, offset image of an animal, one of the doubles blue, and one red, and they’ll consciously register one of them before the other. Do this with many such images and, again, every time they’ll see one of the colors first, but with no particular favoritism. It’s just up to chance which color they’ll see first on a given card.

However, prime the person by having them look at a red screen before each card, and they will tend to (at a frequency much greater than chance) see the red image first.

And it turns out you can prime people by having them merely visualize red (or blue, or whatever relevant color) before seeing the images, and the same results hold, BUT only for self-reported phantasics, NOT for aphantasics.