Iterating Towards Bethlehem

Most of you probably know about Turing machines: hypothetical gizmos built of paper punch-tape, read-write heads, and imagination, which can — step by laborious step — emulate the operation of any computer. And some of you may be old enough to remember the Sinclair ZX-80— a sad little personal computer so primitive that it couldn’t even run its video display and its keyboard at the same time (typing would cause the screen to go dark). Peer into the darkness between these artifacts, stir in a little DNA, and what do you get?

This hairy little spider right here. A pinpoint brain with less than a million neurons, somehow capable of mammalian-level problem-solving. And just maybe, a whole new approach to cognition.

This is an old story, and a popsci one, although I’ve only discovered it now (with thanks to Sheila Miguez) in a 2006 issue of New Scientist. I haven’t been able to find any subsequent reports of this work in the primary lit. So take it with a grain of salt; as far as I know, the peer-reviewers haven’t got their talons into it yet. But holy shit, if this pans out…

Here’s the thumbnail sketch: we have here a spider who eats other spiders, who changes her foraging strategy on the fly, who resorts to trial and error techniques to lure prey into range. She will brave a full frontal assault against prey carrying an egg sac, but sneak up upon an unencumbered target of the same species. Many insects and arachnids are known for fairly complex behaviors (bumblebees are the proletarian’s archetype; Sphex wasps are the cool grad-school example), but those behaviors are hardwired and inflexible. Portia here is not so rote: Portia improvises.

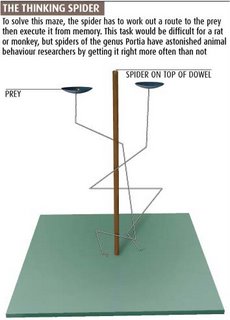

But it’s not just this flexible behavioral repertoire that’s so amazing. It’s not the fact that somehow, this dumb little spider with its crude compound optics has visual acuity to rival a cat’s (even though a cat’s got orders of magnitude more neurons in one retina than our spider has in her whole damn head). It’s not even the fact that this little beast can figure out a maze which entails recognizing prey, then figuring out an approach path along which that prey is not visible (i.e., the spider can’t just keep her eyes on the ball: she has to develop and remember a search image), then follow her best-laid plans by memory including recognizing when she’s made a wrong turn and retracing her steps, all the while out of sight of her target. No, the really amazing thing is how she does all this with a measly 600,000 neurons— how she pulls off cognitive feats that would challenge a mammal with seventy million or more.

She does it like a Turing Machine, one laborious step at a time. She does it like a Sinclair ZX-80: running one part of the system then another, because she doesn’t have the circuitry to run both at once. She does it all sequentially, by timesharing.

She does it like a Turing Machine, one laborious step at a time. She does it like a Sinclair ZX-80: running one part of the system then another, because she doesn’t have the circuitry to run both at once. She does it all sequentially, by timesharing.

She’ll sit there for two fucking hours, just watching. It takes that long to process the image, you see: whereas a cat or a mouse would assimilate the whole hi-res vista in an instant, Portia‘s poor underpowered graphics driver can only hold a fraction of the scene at any given time. So she scans, back and forth, back and forth, like some kind of hairy multilimbed Cylon centurion, scanning each little segment of the game board in turn. Then, when she synthesizes the relevant aspects of each (God knows how many variables she’s juggling, how many pencil sketches get scribbled onto the scratch pad because the jpeg won’t fit), she figures out a plan, and puts it into motion: climbing down the branch, falling out of sight of the target, ignoring other branches that would only seem to provide a more direct route to payoff, homing in on that one critical fork in the road that leads back up to satiation. Portia won’t be deterred by the fact that she only has a few percent of a real brain: she emulates the brain she needs, a few percent at a time.

I wonder what the limits are to Portia‘s painstaking intellect. Suppose we protected her from predators1, and hooked her up to a teensy spider-sized glucose drip so she wouldn’t starve. It takes her a couple of hours to capture a snapshot; how long will it take the fuzzy-legged little beauty to compose a sonnet?

Are we looking at a whole new kind of piecemeal, modular intellect here? And why the hell didn’t I think of it first?

Update 9/1/08: Tarsitano & Jackson published these results in Animal Behaviour. Thanks to Kniffler for the heads-up

1 And isn’t that a whole other interesting problem, how this little beast can sit contemplating her pedipalps for hours on end in a world filled with spider-eating predators? Do certain antipredator reflexes stay active no matter what, or does she just count on immobility and local cover to hide her ass while she’s preoccupied with long-term planning? I’d love to see the cost-benefit of this tradeoff.

Portia photo: by Akio Tanikawa, scammed from Wikipedia under a CC licence.

Maze illo: scammed from New Scientist, under a nine-tenths-of-the-law licence.

Wow.

So where an ant colony pulls of intelligence by having each member carry a bit of the brain, this spider quilts a brain out patch by patch?

I’ve always loved the curious intelligence of jumping spiders, so this put a smile on my face.

In (possible) answer to your concerns regarding the avoidance of prey during the observation periods, take a look at a female of the species. It appears that she would be well camouflaged on the bark of a tree.

…Tachikomas FTW?

(Proto-VN brains? Key to solid state graphene drive algorithms?)

That is dead sexy. Now you’ve got me thinking of your perfectly ordinary human-type person emulating the cognitive capacities of a transapient one step at a time.

It also lends a certain amount of support to those stories of college professors with only a thin rind of brain lining their skulls.

I recall reading an article in National Geographic about these extraordinary spiders — cancelled my subscription in 2005, I believe, so it couldn’t have appeared any later than that.

Yes, I remember that article – fascinating.

The thing about this kind of timelike cognition (does that work?) is that… well, wouldn’t it require a lot of memory to store the work in progress? Perhaps the things the spider chooses/has to store can be mapped on to the critical processes of the higher level system it’s emulating – we could learn a lot about our own brains here.

I’d also be interested in how flexible it can be – much of its planning presumably gets reduced to ‘turn left at the large leaf with the hole in it’, and such – if the leaf is moved, it might well be buggered.

Rosy at Random:

Yes, the limit on any physical Turing Machine (once you’ve given up caring how long it takes to complete a computation, of if it ever does) is memory. And the amount of memory this spider takes to store the results of its computation depends heavily on how they’re represented. I’d think storing the entire brain state would be a big fail, even assuming that memory is denser than the instantaneous state, so there must be some sort of compression or abstraction. And compression and decompression are likely to be some sort of hardwired process; what makes this kind of spider able to do that and not others? Or have we just not seen how the others use it?

I don’t see how it could be flexible; it can’t possibly modify the stored brainstate in real time if it takes so long to build it up in the first place, unless there’s some sort of hardwired conditional branching capability, which seems sort of unlikely. But that’s not really needed; even getting screwed up by changes in the world that invalidate the map, being able to build a plan in advance is a major advantage because it will work a good part of the time.

Cautionary tale on trying to map nervous system activity to computation: I once had a long conversation about how sea slugs think with an invertebrate neurobiologist who studied them. They all have exactly 91 neurons, but more than 91 behaviors. Mapping the flow of neuron states during a behavior shows that each neuron can be used in more than one in a different way in each.

Interesting case, PW. But I’m confused now. You’re not suggesting that this spider’s brain is a serial processing system instead of a parallel distributed processing system like mammalian brains, are you? That would be amazing. Cognitive scientists, many of them originally inspired by the Turing machine, used to think that the best way to model neural systems was serially, with brains computing one step at a time and only then moving onto the next computation. But we’ve known for decades that brains (I don’t know if insects and mammals are different in this regard) do widespread, distributed parallel processing. So the Turing model is fundamentally flawed.

Now given some of the remarkable things that connectionists like Paul Churchland have been doing with even simple PDP networks, I guess I’m not that surprised to hear that this spider can do all this fancy stuff. They’ve gotten really simple networks with just dozens of nodes to pull off very complicated recognitional feats like distinguishing faces, among other things.

The other thread here is your claim about the spider’s adaptability. I haven’t read the article, but I wonder how they’ve gone about or would go about testing such claims about the spider’s flexibility. Then the question is–and the point you’re making–how is it that such a small system can achieve so much plasticity? But again, I wonder if there is a difference in kind here between the spider and mammals. Big brain mammals can pull these things off and just do a lot of other stuff.

MM

This appears to be Jackson’s major article on the topic: http://tinyurl.com/78grz4

Pity nobody seems to have followed up on the neurology side of things.

Matt McM:

….I wonder how they’ve gone about or would go about testing such claims about the spider’s flexibility….how is it that such a small system can achieve so much plasticity? But again, I wonder if there is a difference in kind here between the spider and mammals. Big brain mammals can pull these things off and just do a lot of other stuff

I was having similar thoughts?

The coat hanger test mimics the set-up of natural food-getting behavior of the Portia, yes? That could mean the spider isn’t being flexible at all in the sense that we’re flexible – we can deliberately acquire new skills, and she’s running her limited set of programs only. (Interesting that her programs themselves have any flexibility. That she can work toward the prey she can’t see does sound mammalian, doesn’t it? I wouldn’t have thought it was in the spider toolkit.)

If I were testing her further, I would try making the “maze” progressively less forest-floor-debris-like, and/or more complex – can you handle 2 branchings? 3? 20? At what level of branching in the maze do 50% of spiders fail to reach the prey? How long does the spider retain the memory of the incident where it would have been better to jump-then-swim? If she remembers for 6 minutes, that’s one thing, but how about 6 days, or 6 months? What if she can handle more maze complexity than a rat, or retain a memory for as long as an elephant – wouldn’t that leave animal behaviorists scrambling!

It’s nice to see spiders getting good press for a change, btw.

The thing about turing serial-type processing is that it’s meant to be equivalent to parallel processing… but equivalent in an abstract sense, one that does not include much sense of efficiency and practicality.

So, while it could be emulating parallel cognition serially, I doubt it. And if it is, it would be fascinating to see how it does it.

And, I wonder… this migt be the sort of brain that upscales with dramatic performance improvement. After all, its main limitation would seem to be working memory/processing space. How long is their reproductive cycle, and how long would a breeding program take?

Yes, I realise I’m proposing that we create giant sentient killer spiders.

Why would they require sentience? They seem to be doing just fine without it, if the speculation re: their processing is at all correct. (Though, I’m all in favour of making Tachikomas real, and this would be a good step.)

Ah, I think I chose that word more for its fit than its accuracy.

But I wonder which is scarier – super-intelligent sentient or non-sentient monster spiders?

I think sentience is scarier – it could _hate_ you then.

But would it hate you, or would it love you, possibly with a little garlic butter…

nom nom nom etc

And I sprang from my slumber drenched in sweat

like the tears of one million terrified brothers

and roared,

“Hear me now,

I have seen the light,

they have a consciousness,

they have a life,

they have a soul.”

Damn you!

Let the rabbits wear glasses.

Yeah, we’re utterly screwed when these babies try reconciling Charlotte’s Web with Shelob.

Rodney Books has been doing some really interesting work on this kind of thing for a number of years. His work diverges from the inheritors of Turing, though in that he’s not so much interested in computation as in interaction and that ‘intelligence’ is the result of processing sensory data.

I wonder what the implications of this kind of neural processing are to his work. We’ve assumed for a long time that AI machines would have to be able to process quickly. Is it possible to have a sentience that moves at a slow crawl?

razorsmile said…

That is dead sexy. Now you’ve got me thinking of your perfectly ordinary human-type person emulating the cognitive capacities of a transapient one step at a time.

Exactly.

It also lends a certain amount of support to those stories of college professors with only a thin rind of brain lining their skulls.

Except those guys could interact with the world in real-time, as far as I know. There are, however, some folks who kind of zone out into a fugue state when confused. I wonder if there might be some kind of analogous iteration going on in some of those cases.

Matt McCormick said…

Interesting case, PW. But I’m confused now. You’re not suggesting that this spider’s brain is a serial processing system instead of a parallel distributed processing system like mammalian brains, are you?… we’ve known for decades that brains (I don’t know if insects and mammals are different in this regard) do widespread, distributed parallel processing. So the Turing model is fundamentally flawed.

I’m not so much suggesting that the spider’s brain is serial so much as the algorithms it's running are. I invoke Turing machines and ZX-80s only because those were the first things to spring to mind when I encountered this story; the (admittedly superficial) similarity lay mainly in the fact that in all these cases, limited resources are addressed by performing usually-parallel tasks in sequence. (That said, though, since we can model neural nets on real-world computers, a Turing machine could theoretically do so as well— meaning that the Turing model does, in fact, encompass parallel processing. Or am I missing your point?)

… The other thread here is your claim about the spider's adaptability. I haven't read the article, but I wonder how they've gone about or would go about testing such claims about the spider's flexibility. Then the question is—and the point you're making—how is it that such a small system can achieve so much plasticity?

and then Kniffler pointed out…

This appears to be Jackson’s major article on the topic: http://tinyurl.com/78grz4

Pity nobody seems to have followed up on the neurology side of things.

I’ve updated the main post to include this citation: Animal Behaviour is a first-rate journal, so the research is officially credible.

But ol’ Knif is right: the paper is purely behavioral, with none of the neurological underpinnings mentioned in the New Scientist article. And while I do have a very soft spot in my heart for New Scientist, they have been known to make mistakes. Back in the day they even did a piece on some of my own research, and they misreported my central finding by an order of magnitude. It was only a misplaced decimal point, but it made the difference between mere hyperthermia and the spontaneous combustion of harbour seals. (I actually preferred their interpretation to mine.)

So, once again: grain of salt time. But still, great fodder for sf speculation, no?

Moving down the list, bec-87rb (the non-S&M bec-87rb, presumably) said…

The coat hanger test mimics the set-up of natural food-getting behavior of the Portia, yes? That could mean the spider isn’t being flexible at all in the sense that we’re flexible – we can deliberately acquire new skills, and she’s running her limited set of programs only. (Interesting that her programs themselves have any flexibility. That she can work toward the prey she can’t see does sound mammalian, doesn’t it? I wouldn’t have thought it was in the spider toolkit.)

This raises an interesting question of where you draw the line between Portia and Persons. Spider’s got a fixed toolkit, you say; we can acquire new tools. Fair enough, especially if the arthropod kit only contains a handful of tools. But suppose Portia‘s toolkit contains 10,000 different strategies, or 100,000: she’s still limited, still ultimately inflexible. The argument holds. But damn, that’s a lot of tools. You might have to watch her for a long time before it becomes obvious that she isn’t just making stuff up on her own.

Now, let’s say she’s got this absolutely kick-ass socket set where the wrench is a single tool, but can be mixed-and-matched with a whole bunch of heads. Still a limited inflexible set of tools, but now we’re using them in combinations — and at some point, someone's gonna point out that human language itself is a limited inflexible set of letters and rules, which can nonetheless be used in combination to vast effect. And then someone else is going to wonder whether human thought might just be a set of pre-fitted reflexive tools being used in combination, far more numerous than anything that could fit into dear ol' Portia‘s head but that’s a difference of degree not of kind, hmm?

Rosy At Random said…

…So, while it could be emulating parallel cognition serially, I doubt it. And if it is, it would be fascinating to see how it does it.

It would be. But whether or not the little beastie’s precisely modeling parallel processing, she’s still splitting some kinda big task into bite-sized chunks and chewing them one at a time, and I think that’s cool. Who knew the little crawlies were so Object-Oriented?

Yes, I realize I’m proposing that we create giant sentient killer spiders.

Marry me.

But I wonder which is scarier – super-intelligent sentient or non-sentient monster spiders?

Well, you all know where I stand on that issue…

Thomas said…

We’ve assumed for a long time that AI machines would have to be able to process quickly. Is it possible to have a sentience that moves at a slow crawl?

Isn't one of the tenets of the Hard-AI types that the medium is irrelevant, it's the flow of information that counts? Which would mean that theoretically you could build a sentient mind out of habitrail tubes put together like dendrites and axons, using ping-pong-balls to represent the electrical current. That would be a very very large AI indeed— and very very slow as well.

In a moment of unthinking passion at the thought of sentient killer spiders, I asked someone by the handle of “Rosy at Random” to…

Marry me.

But now I take it back. Rosy’s a dude.

Man, that’s a really misleading handle you’ve got there.

Je ne regrette rien!

I like my nickname being Rosy mostly cause of these wonderful moments of complete bemusement it provokes. Although this _is_ the first marriage proposal it has led to….

Oh, and I just remembered that I meant to respond to Madeline‘s Charlotte’s Web post:

“Tasty Pig!”

Which, while cute, cannot hold a candle to Robot Chicken’s run at the same silky little icon: “2.99/lb.”

Which is at 6:35 here, folks!

(There we go; forgot to put the href in)

Mrs. Mike Watts wrote:

6:35 here, folks!

I can no see it, big guy..

Rosy (whose screen name might also be taken to mean one who blushes unpredictably), I think you mean: “SOME [TASTY!] PIG” — written in silk, of course. 😉

Ha! Anyway, the link seems to work for me… perhaps this one (no HTML this time): http://www.joost.com/home?playNow=226g97l

Oh, and Maddy: “Send More Pigs”?

/more apt possibilities trumped by reference to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wylpeAXYcBQ (@ 2:20)

http://www.joost.com/home?playNow=226g97l

Thanks, Rosy, but no joy over here. Must be because I’m in the colonies. No probs, though, I have sweet sweet vodka and the internet to keep me company.

Rosy: “MOAR PIGS PLZ”

/lolcharlotte

Thomas said…

We’ve assumed for a long time that AI machines would have to be able to process quickly. Is it possible to have a sentience that moves at a slow crawl?

Peter Watts said…

Isn’t one of the tenets of the Hard-AI types that the medium is irrelevant, it’s the flow of information that counts? Which would mean that theoretically you could build a sentient mind out of habitrail tubes put together like dendrites and axons, using ping-pong-balls to represent the electrical current. That would be a very very large AI indeed— and very very slow as well.

On this topic, you should check out Bruce Sterling’s “The Lustration”, one of a handful of good stories in the otherwise mediocre Eclipse One, edited by Jonathan Strahan.

All creatures of this earth are equally intelligent. Any creature that is born naked and hungry in the fucking cold dirt and can make happen, and then support others of it’s own issue is not stupid. Where do people get off thinking other creatures are inferior?

The day I see a fruitfly solving a crossword puzzle, I’ll let you know.

Weren’t scramblers supposed to work in a similar way? Like, their neurons (or whatever they had for neurons) processing sensory data, and being intelligent when no new sensory information was around to process?