“PyrE. Make them tell you what it is.”

At the end of one of the classic novels of TwenCen SF, the protagonist — an illiterate third-class mechanic’s mate named Gulliver Foyle, bootstrapped by his passion for revenge into the most powerful man in the solar system — gets hold of a top-secret doomsday weapon. Think of it as a kind of antimatter which can be detonated by the mere act of thinking about detonating it. He travels across the world in a matter of minutes, appearing in city after city, throwing slugs of the stuff into the hands of astonished and uncomprehending crowds and vanishing again. Finally the authorities catch up with him: “Do you know what you’ve done?” they ask, horrified by the utter impossibility of stuffing the genie back in the bottle.

He does: “I’ve handed life and death back to the people who do the living and the dying.”

We are approaching such a moment now, I think. I’m speaking, of course, about the new gengineered ferret-killing — and potentially, people-decimating — variant of H5N1. And call me crazy, but I hope the people with their hands on that button take their lead from Gully Foyle.

For the benefit of anyone who hasn’t been following, here’s the story so far: your garden-variety bird flu has always been a bug that combines a really nasty mortality rate (>50%) with fairly pathetic transmission, at least among us bipeds (it doesn’t spread person-to-person; human victims generally get it from contact with infected birds). But influenza’s a slippery bitch, always mutating (which is why you keep hearing about new strains of flu every year); so Ron Fouchier, Yoshihiro Kawaoka, and assorted colleagues set out to poke H5N1 with a stick and see what it might take to turn it into something really nasty.

The answer was: less than anybody suspected. A few tweaks, a handful of mutations, and a bite from a radioactive spider turned poor old underachieving bird flu into an airborne superbug that killed 75% of the ferrets it infected. (Apparently ferrets are the go-to human analogues for this sort of thing. I did not know that.) By way of comparison, the Spanish Flu — which took out somewhere between 50-100 million people back in 1918 — had a mortality rate of maybe 3%.

When Fouchier and Kawaoka’s teams went to publish these findings, the birdshit really hit the fan. The papers passed through the US National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity en route to Science and Nature; and that august body strongly suggested that all how-to details be redacted prior to publication. Never mind that the very foundation of the scientific method involves replication of results, which in turn depends upon precise and accurate description of methodology: those very methodological details, the board warned, “could enable replication of the experiments by those who would seek to do harm.”

Both Science and Nature have delayed publication of the scorching spuds while the various parties figure out what to do. Fouchier and Kawaoka have also announced a 60-day hiatus on further research, although it’s pretty clear that they intend to use this time to present their case to a skittish public, rather than re-examining it.

Then what?

Opinions on the subject seem to follow a bimodal distribution: let’s call the first of those peaks Bioterrorist Mountain, and the other Peak PublicHealth. Those who’ve planted their flags on the former summit argue that this kind of research should never be released (or even, some say, performed), because if it is, the tewwowists win. Those on the latter peak argue that nature could well pull off this kind of experiment on her own, and we damn well better do our homework so we know how to deal when she does. Somewhere in between lie the Foothills-of-Accidental-Release, whose denizens point out that even in a bad-guy-free world, chances of someone accidentally tracking the superbug out of the lab are pretty high (one set of calculations puts those odds as high as 80% within four years, even if the tech specs are kept scrupulously under wraps).

Right up front, I do not trust the residents of Bioterrorist Mountain. The National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity has a diverse makeup, including representatives from the Departments of Commerce and Energy, Justice, the Interior — and oh, Defense and our old friends at Homeland Security. They’ve already read the details that they would deny to others, and you can be damn sure that none of them are volunteering to have their memories erased in the name of global security, no sirree. They’re not so much worried about the efforts of all who’d seek to do harm; they’re really only worried about what the other guys might do. Anyone who thinks the US wouldn’t gladly use the fruits of such labor against those it considers a threat has not been paying attention to the recent debates among Republican presidential contenders. And once the government starts deciding who gets to see what parts of this or that scientific paper, you have in effect (as one online commenter points out) “essentially a biological weapons program”1.

Let’s assume, though, that we live in some parallel reality where realpolitick doesn’t exist, Truth Justice and the American Way is not an oxymoron, and the motives of those who’d keep these data under wraps really are purely defensive. Even in the face of such driven-snow purity, suppressing potentially dangerous biomedical findings only works if the other guys can’t reinvent your particular wheel: if either the bug itself is hard to come by, or the villains from Derkaderkastan don’t know the difference between a thermos and a thermocycler. But avian flu isn’t uranium-235, and one of the most surprising findings about this bug was how easy it was to weaponise. (Up until now, everyone figured that increased contagion would go hand-in-hand with decreased lethality.)

Suppression might be a valid option if your enemies have about as much biological expertise as, say, Rick Santorum. That is not a gamble any sane person would make. To quote the head of the Centre on Global Health Security in London: “[T]he WHO Advisory Group of Independent Experts that reviews the smallpox research programme noted this year that DNA sequencing, cloning and gene synthesis could now allow de novo synthesis of the entire Variola virus genome and creation of a live virus, using publicly available sequence information, at a cost of about US$200,000 or less.”

On the other hand, you have the very real likelihood of an accidental outbreak; of natural mutation to increased virulence; of the bad guys figuring out the appropriate tweaks independent of Kawaoka’s data. In which case you’ve got a few thousand epidemiologists who’ve been frozen out of the Culture Club, improvising by the seat of their pants as they go up against something that makes the Black Plague look like a case of acne.

The folks on Peak PublicHealth believe that this is too important a danger to be thought of in terms of anything as trivial as national security. This is a global health issue; this is a pandemic just waiting to happen, with a kill rate like we’ve never seen before. Fouchier’s and Kawaoka’s research has given us a heads-up. We can get ahead of this thing and figure out how to stop it before it ever becomes a threat; and the way to do that is to get the community at large working on the problem. The second-last thing you want is a species-decimating plague whose cure is in the hands of a single self-interested political entity. (Admittedly, this is marginally better than the last thing you want, which is a species-decimating plague with no cure at all.)

Back in 2005, Peter Palese and his buddies reverse-engineered the 1918 Spanish Flu virus. They published their findings in full. The usual suspects cried out, but now we know how to kill Spanish Flu. That particular doomsday scenario has been averted. It should come as no surprise that Palese plants his flag on Public Health, and he makes the case far more eloquently (and with infinitely greater expertise) than I ever could.

And down here in the corner, a recent paper in PLoS One that seems curiously relevant to the current discussion, although none of the pundits involved seems to have noticed: “Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Therapeutics“, by Rider et al. It reports on a new antiviral treatment that goes by the delightfully skiffy acronym DRACO, which induces suicide in virus-infected mammalian cells and leaves healthy cells alone. It’s been tested on 15 different viruses — dengue, H1N1, encephalomyelitis, kissing cousins of West Nile and hemorrhagic fever to name a few. It’s proven effective against all of them in culture. And it keys on RNA helices produced ubiquitously and exclusively by viruses, so — if I’m reading this right — it could potentially be a cure-all for viral infections generally.

We may already be closing on a cure for the ferret-killer, and a lot of its relatives besides.

So, yeah. We can either try to stuff the genie back in the bottle, now that everyone knows how easy it is to make one of their own. Or we can give life and death back to the people who do the living and the dying.

I say, get it out there.

1Of course, you could point out that the US has doubtless had its own biowarfare program running for decades, and I would not disagree. That doesn’t change the point I’m making here, though.

Agreed. Captain Tripps didn’t cut a swath through humanity because the research had been done, but because it hadn’t been finished.

BRB, moving to Madagascar.

Well, I heard about the ferret virus paper, I did not hear about the recent research in antivirals. That’s downright hopeful news. For a variety of reasons. AIDS, anyone?

My main problem is the middle ground of accidental release. From a cursory read of it when the story first broke, they were running these tests at biosafety level 3, which is designed for bugs we have treatment for, while a currently untreatable disease (which I would say is a good assumption for what is essentially a new disease) should be at biosafety level 4.

That said, the research has to be done. If there are “novel” aspects of the creation of the virus, I can see withholding them from publication and sharing them on a more limited basis, but you can’t ignore it and hope it goes away.

There was a recent report that the mortality of H5N1 might not be as high as commonly believed; the numbers are based on cases treated vs deaths, but a scan of the population finds that there are immunological signatures in the population that indicate exposure to H5N1 – the argument is that most of the people that get sick from it don’t actually go to the hospital, so the denominator in our mortality calculations is a lot lower than it should be.

If so, it makes a stronger case for information dispersal – the potential for catastrophe isn’t as large as everyone is proclaiming.

And it keys on RNA helices produced ubiquitously and exclusively by viruses, so — if I’m reading this right — it could potentially be a cure-all for viral infections generally.

For the Love of st.Darwin, where the hell should I come to fill up my gloom tank, if even you spread this kind of hopeful news.

Seriously. Now I find all my meticulous preparations for an eventual deadly flu pandemic were for naught. The physical training, the cold shower regimen, the cache of weapons.

(I haven’t had a case of the flu in this millenium, and neither have my parents or sister. We just never really catch it.)

Bloody human ingenuity.

@Madeline Ashby

But…Captain Trips was a Gift From God! Didn’t you read the book…? 😉

It’s a tricky one, isn’t it? The example of the flu bug being a lot easier to get hold of then U-238 is interesting, as the A-Bomb is what first came to my mind – while the general principle of how to make a nuke is common knowledge, there are crucial technical details that have never been made public that mean you’d need some serious research and brainpower to make one even if you could somehow source the parts.

The risk is so severe that such secrecy is warranted, but presumably shared between friendly governments – or did the NATO states and Israel make up their own bombs, or perhaps go down the Russian route?

You might argue the risk is equally severe with a super-virus, so the secrecy should be equal, regardless of the difference in difficulty of obtaining the base materials. Peter has written several stories on the theme of the cautionary principle – keep your heads down, lest those beligerent high-tech aliens find us and zap us – which would surely weigh on the side of not spreading dangerous knowledge, no matter what?

(FWIW, in this case I think spreading the love is more than justified – I’d feel better dying from a lab mistake or an enemy attack, than from a randomly mutated bug that I could have been saved from if my government hadn’t insisted on all that cloak-and-dagger shit)

Hmm…A cutesy fucking icon! 😮

I agree with releasing the research. It’s bad enough that some of these politicians want to teach intelligent design in schools. Limiting knowledge for the prevention of potential pandemics just makes them more recognizable as criminals. In a way, I think they probably wouldn’t mind killing off a great number of their constituents, just like they didn’t mind what happened with hurricane Katrina.

Thanks for the info, Peter, even though you really have a knack with scaring the hell out of people. But then, the world we live in does that already.

The reality is, there has never been a successful attempt to put the genie back in the bottle. The development of nuclear weapons became a certainty from the day that Madame Curie made her discoveries. Should her research have been silenced? She would have lived longer if it had, but our ability to diagnose medical problems would be greatly diminished.

It could also be argued that biological weapons became a certainty the day after the germ theory of disease was proposed. And attempts at eugenics became a certainty following Darwin’s publication.

Even though these discoveries have all resulted in “bad” things happening, they have also resulted in great benefits. The publishing of this paper will not increase the risk to anyone because, almost certainly, all of the tools and techniques used to create this super virus are already well known.

Nuclear weapons are the true peacekeepers.

You up the stakes by building atomics. A country with enough nukes, if invaded, can blast the invading army, or incinerate the invaders’ cities, or destroy itself.

How is that a not good thing?

Had it not been for nukes, I believe that Western Europe would’ve eventually fallen to the Soviets.

You think just USSR built 90,000 main battle tanks because it was fearing a US invasion?

I think releasing the information is a lot safer than not doing so. While ‘sufficiently together to summon up half a million bucks and a decent bioscientist’ and ‘totally, utterly, negative-sum bonkers’ might not be completely mutually exclusive, they’re certainly not a common combination.

Meanwhile, if the information is released, the likely consequences of an actual outbreak (natural or not) are probably less ugly – nobody has any great incentive to hoard expertise or resources in the name of national defense, so something approaching the best viable countermeasures are more likely to be prepared, faster, than if every piece of information was weighed against its future strategic value.

(I was going to ramble on for a while about whether suppressing the research would weaken deterrence between nations, too, but belatedly realized that angle’s rendered completely moot by the fact that all the major players undoubtedly have much worse than this – the fruit of half a century’s dedicated research – already stashed away. Derp).

“DRACO, which induces suicide in virus-infected mammalian cells and leaves healthy cells alone.”

So when someone contracts influenza, how many of their cells are infected? Is it 90%, 10%, 1%? Something much much smaller? Presumably certain tissue types have higher rates than others…?

by the fact that all the major players undoubtedly have much worse than this – the fruit of half a century’s dedicated research – already stashed away. Derp).

Why would the major players have something that’s like a doomsday weapon and keep it secret?

Weapons so secret no one knows about them are not much of a deterrent.

Whatever one thinks about the notion of trying to contain nuclear bomb technology, the fact is the bombs don’t assemble themselves while new strains of flu regularly do and one just like the ferret-killer (or worse) has a reasonable chance of doing so.

Unfortunately I don’t have scholarly references at hand, but more than one BBC science podcast (for whatever they might be worth) is reporting that each of the key mutations that make this lab version so deadly is fairly common in wild flu populations, just not *yet* combined in the same strain.

Given the source of that factoid you can take it with as many grains of salt as you think are appropriate, but the fact remains that unless I’m missing something important, nature — with a bazillion generations of flu as its laboratory — has a decent chance of replicating these results all on its own.

If that happens while some dim bulbs in the dee-fence industry are throttling research we are going to get caught with our metaphorical pants down at a critical moment. At least those of us who don’t have a hollowed-out mountain to hide in are going to.

I’d like to know how publishing details of creating a new, improved form of flu virus will lead to more cures. Not just general waffle about more knowledge is good. Is no-one doing research on flu vaccines already? Would the “Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Therapeutics” people have developed a new ice cream flavour instead if Fouchier et all hadn’t done this work?

People have used the IT industry “full disclosure” as an example. It doesn’t quite work, though, because the nature of the research is different. With computer security weaknesses, we know what has to be done to fix the problem – if you like, we already have the vaccine, it hasn’t been applied.

And full disclosure is the last step, not the first. The mostly accepted way is for a security researcher to notify the software company “if I feed this string into your database browser, I get unlimited access and can clean out your bank account.” Then you wait a week or two. Full disclosure is the backup threat to the software company: “if you pretend there is no problem, I’ll tell everyone in the world (or at least everyone with a subscription to CERT/BugTraq) how to clean out bank accounts. Your customers will be very unhappy.” It’s necessary because some companies did prefer to sit on problems.

Now, from my limited knowledge, Fouchier et all are proposing what the IT industry calls a zero day exploit: “Here’s how to create a deadly flu virus. We hope someone can find a cure.”

OK, it’s a target for research. Getting back to my original question, is it going to lead to better research? If the virus is mutating all the time, how will finding a vaccine for this particular variant help?

@Hugh

It’s not so simple. Vaccines work against a number of mutations. Flu vaccine that’s hawked commercially is different year to year I believe, and should work against that year’s flu. Use your google skills.

There’s got to be a good explanation of basics of immunology tailored for smarter people like you.

If the virus is mutating all the time, how will finding a vaccine for this particular variant help?

If it mutates, the changes are small at first, so the vaccine is good for some time. That’s my guess… I’m not a biologist or doctor.

Lanius:

It’s not a good thing when the guys with the nukes have been hacked into believing that apocalypse is their ticket to a sublime afterlife, in which case nuclear war becomes a incentive not a deterrent. It’s not a good thing when I hate the other guy so much that I’d gladly burn my own face off just to give him a bloody nose — which is, as it turns out, pretty much the way revenge is wired into us neurologically. In short, it’s not a good thing whenever those holding the nukes are not agents of scrupulously rational self-interest. Which is to say…

Weapons aren’t built exclusively as deterrents. Weapons are also used to kill people; and a biological weapon, which could pass as just another one of nature’s experiments, could decimate an enemy without that enemy knowing who’s attacking it, or even that it is under attack. Way better than drones or nukes; those things have serial numbers.

Hugh:

Follow my link to Peter Palese’s article; he recounts an explicit case study in support of that point. Let me also take this opportunity to point out that coming up with new cures is only one advantage (albeit a big one) of keeping science in the public domain. Another advantage is that any existing cures do not remain the property of any one nation, who might otherwise feel safe in using it against others because after all, their people won’t be killed…

Those therapeutics do look promising; but I think that most would agree that if you’re not aware of the threat, you won’t be working on countermeasures. If someone published a paper showing that an asteroid was coasting in-system to flatten the planet, would you dismiss it as “general waffle” to the folks who suddenly found themselves working round-the-clock on asteroid-deflection techniques?

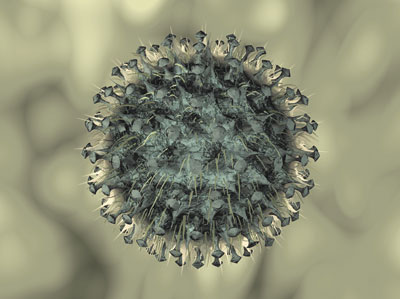

That photo is scary even if you don’t know what it is. It’s disturbing! But interesting.

In short, it’s not a good thing whenever those holding the nukes are not agents of scrupulously rational self-interest.

Darn, I shoulda posted my last comment not in the previous blog entry, but here. I’d like to suggest that the rational self-interest that keeps people from nuking their neighbors does not work alone; it is not a solitary deterrent?

Moral repulsion plays a part; rational self-interest tells you that you ought to use nukes if it harms the other side more than yours and your side can recover afterward. Under that schema, we ought to have had half a dozen rational nukings since WWII, but, strangely, no. I think what happens is that when it comes to war, even though war is always an atrocity, there is some “line” that nuking crosses. Maybe because Hiroshima and Nagasaki were so gratuitous and the effects so horrific and well-documented? I’m not saying it can’t happen ever, I’m saying when someone is thinking, hm, what if I nuke Egypt, one of the unspoken considerations is how generally morally repulsive it is.

Of course, I think this because I believe that no man is totally rational, and many of his impulses are emotionally-driven, and that can be a good or a bad thing. I have to say that it has puzzled me that we are mostly all still here in world bristling with devastating lethal weaponry.

Is it just luck? I don’t know.

science in the public domain. Another advantage is that any existing cures do not remain the property of any one nation, who might otherwise feel safe in using it against others because after all, their people won’t be killed…

Like “The Moat” by Greg Egan if you have read that.

It would be pretty cool to read some brain child of you two.

Lanius, on January 26th, 2012 at 12:32 pm Said:

by the fact that all the major players undoubtedly have much worse than this – the fruit of half a century’s dedicated research – already stashed away. Derp).

Why would the major players have something that’s like a doomsday weapon and keep it secret?

Weapons so secret no one knows about them are not much of a deterrent.

. . . . spoken in a Peter Sellers faux German accent, I assume?

@Hljóðlegur: “Moral repulsion plays a part; rational self-interest tells you that you ought to use nukes if it harms the other side more than yours and your side can recover afterward.”

I think that you are placing too much importance on the moral aspect. Self-interest is not limited to what the opposite side would do if you nuked it. You also have to factor in what every other country in the world would do to you if you nuked another country.

America got away with it at the end of the war because it was new and because the entire world was sick of the war. But, even many of its closest allies would turn against them if they preemptively nuked any other country, even its worst enemy.

OK, people more scientifically competent than me think that this research will lead to better cures. I’m on board with publishing.

I’ve been thinking about why this upsets so many people. For me, it’s because they created a new virus. They didn’t look for a mutation that had already occurred but not widespread. They didn’t reconstruct the Spanish Flu virus already known to have caused a pandemic. Deliberately, with the best intentions, they made a new and more lethal form.

To use Peter’s example, they didn’t publish a paper showing an asteroid was coasting in-system to flatten the planet, they pushed an asteroid off course.

“Moral repulsion plays a part; rational self-interest tells you that you ought to use nukes if it harms the other side more than yours and your side can recover afterward.”

The opportunity cost of having to recover from a few dozen fried cities is steep enough that, even if a first-strike leaves you ahead of everyone else, there has to be a compelling case for hitting the big red button in absolute terms, too.

Ruling over the biggest pile of irradiated ashes just isn’t a particularly appealing prospect for anyone with the resources to amass a nuclear arsenal in the first place.

“[Science fiction novels] can explore the consequences of new and proposed technologies in graphic ways, by showing them as fully operational. We’ve always been good at letting cats out of bags and genies out of bottles, we just haven’t been very good at putting them back in again. These stories in their darker modes are all versions of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice: the apprentice finds out how to make the magic salt-grinder produce salt, but he can’t turn it off.”

Margaret Atwood, ‘Aliens have taken the place of angels’.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2005/jun/17/sciencefictionfantasyandhorror.margaretatwood

Weapons aren’t built exclusively as deterrents. Weapons are also used to kill people; and a biological weapon, which could pass as just another one of nature’s experiments, could decimate an enemy without that enemy knowing who’s attacking it, or even that it is under attack. Way better than drones or nukes; those things have serial numbers.

Drones or nukes don’t mutate, spawn new copies in places where you don’t want them, and generally do what they’re told, and cease to function if not maintained.

If they don’t, if you create mechanical, self-replicating and self-directing weaponry, you end up with something like New Hokkaido in Richard K.Morgan’s Woken Furies.

First time posting at this blog, amusing

My agreement would go to the group that’s going “But what if it escapes?” but for one thing, I’ve been recently reading the book Biohazard by one Ken Alibek who describes his time with the Soviet Union in their biowarfare division.

He describes in the prologue his decision to write the book because educated westerners he’d met didn’t believe it was actually possible to do what he’d been doing.

Now from what I’m aware Russia hasn’t had some virus escape and kill lots of people in spite of their whole massive economic turmoil in the 1990’s

So assuming the researchers promise to be paranoid with their research, I’m fine with it

Anon – Self-interest is not limited to what the opposite side would do if you nuked it. You also have to factor in what every other country in the world would do to you if you nuked another country. America got away with it at the end of the war because it was new and because the entire world was sick of the war.

You and I are in essential agreement – I’m not saying there is NO rational reason to avoid nuking, I mean there is some rationale for nuking, and that one non-rational factor we hadn’t brought in was that individuals in countries experience moral repulsion to some certain levels or types of weapon deployment.

Consider tactical limited nuking. Remember, at some point that was on the table for the US military? Yet we just never did it. I suspect part of the reason is that after Hiroshima/Nagasaki, the idea of using nuclear blasts as weapons had associated with it a level of horror that made it unusable in most situations. The decision not to use nukes of any size in war might have been rational in the sense that it involved a calculation as to “how it would make us look” but in order for that to work, you need that substrate of moral revulsion, that “taint” of evil.

I suppose the thing to do is to have several responsible organizations such as university immunology departments all send delegates to several research facilities to work out the methods for creating immunizations with a fairly broad and long-lasting effect, and once various corporations and their stockholders have gotten filthy rich and very large numbers of people have been immunized, release the information.

Peter Watts rightly points out that the Spanish Influenza only killed about 3-percent of people during its passage. It’s responsible for the fact that at one time the decadal US Census did report an actual decrease in population, in 1920.

What fascinates me is the potential effects on the society of the survivors. Shortly before the news of this research came out, I whipped out a 50-page “advisory” piece in the style of the sort of FEMA manual that gets passed out after natural disasters such as mega-quakes and Cat 5 hurricanes. As part researching it, I ran some numbers and as it turns out, if something did get released (or evolved) that took out 2/3rds of global population, that would only set us back to the global population extant in the middle of WWII. My “advisory” was meant to read like something hastily distributed to all available Kindles in the last few days of operative internet near the conclusion of a pandemic with a 99-percent mortality rate… and even that level of mortality knocks back global population only to about the same as that of the Roman Empire in the 3rd Century CE. The sheer numbers of humans now living seems to indicate that, like cockroaches, we’re practically ineradicable.

Given that the evolution, or intentional design with accidental release, of such an organism is probably nearly inevitable, we might want to worry less about the politics of the modern day and look more to planning for the clean-up in a probably fairly near future of aftermath to the worst pandemic since European diseases wiped out 95 (or more) percent of New World natives.

Just thought I’d add my two cents of pessimism and gloom.

@Lanius “Drones or nukes don’t mutate, spawn new copies in places where you don’t want them, and generally do what they’re told, and cease to function if not maintained.”

This may be true, we’re working on it.

What we’re looking at here is the democratization of doomsday. Making this information public will certainly give researchers the opportunity to develop countermeasures to deadly bioweapons. The question is: Can a reactive biological defense program possibly keep up with each and every new modified virus, spore, etc. that is made and must be contained or properly disposed of?

Look at the 1979 Sverdlovsk Anthrax Leak in what is now Ekaterinburg, Russia. 94 people dead. The USSR had no intention of killing their own citizens in this instance, but basic human incompetence led to that outcome. Now imagine (and I stress the word imagine) that greater transparency in biowarfare projects (which is what this H5N1 tweak amounts to, regardless of intentions) is allowed to continue unabated, is in fact, actually encouraged. It won’t immediately lead to some panacea defense. Life is endlessly mutable. What would we would be faced with then is a situation like in Maelstrom where entire cities would be incinerated for the greater good.

And that would be the best case scenario.,.

Transparency is usually a good thing. But in this case, I think it simply will leave a lot of bodies in its wake.

The argument in The Stars My Destination for putting PyrE in the hands of ordinary folks seems familiar somehow … oh right. Replace “PyrE” by “fully automatic assault rifle” and you’ve got the standard gun nut rant about a heavily armed citizenry being the only defence against oppressive governments.

Me, I trust the military of my country (Australia) with deadly weapons a lot more than anyone else, because I vote.

In Westernised countries the military have a well defined hierarchy of command which ends with the civilian government. It’s not perfect, but there are enough checks and procedures to ensure that accountability for how weapons get used ultimately ends at me and my fellow voters. Even in the cold war USSR and modern China, the government couldn’t/can’t ignore the population.

You can see this at work in the US Republican primaries, with the religious nuts being voted off the island. Even among self-selected adherents to the cause, there’s some recognition that babbling about Jesus and End Times is relatively harmless in a state governor, but not someone you want with their finger on the big red button.

(If I wanted to change the USA to a nuclear first use policy, I’d use the Norman Spinrad short story “The Big Flash” as my template.)

And it works, as shown by homicide statistics. If you’re a US citizen, your chance of being killed by the US military is very very low, despite the awesome firepower they have. Same for the chance of an Australian citizen being killed by the Australian military, French, Canadian, and so on.

There’s a slightly higher chance of being killed by the police, but the real threat comes from your family and social network. (And I’m equally dangerous to them.) They are the people I trust least with weapons, because they’re the most likely to try and do me in.

There have been several mentions here about the Spanish flue and the fact that its mortality rate was only about 3%. But i haven’t seen anything about the fact that it was as high as it was largely because of the war and the conditions that favoured the incubation and spread of the disease.

Most decisions made by people during a war, ragrdless of the side, are made byii people who think they are moral and doing the right thing. This has resulted in the dropping of nuclear bombs, chemical attacks, biological attacks, carpet bombing, incendiary bombing, etc. Given that these have been decided by moral people, i hope never to see a decision made by imoral people.

Which emphasizes my point. The decision not to use a weapon (nuclear, biological, emotional, whatever) has more to do with evaluating the possible response than it has to do with any moral balacing act.

It’s not a good thing when the guys with the nukes have been hacked into believing that apocalypse is their ticket to a sublime afterlife, in which case nuclear war becomes a incentive not a deterrent.

True, but I don’t think that any countries anywhere are ruled by people who think like this. If Ahmadinejad was really desperate to die for his faith, well, he had a great chance to do so between 1980 and 1988, and he didn’t take it. Rulers tend to be rational. Not always intelligent, or well informed, or moral, but you don’t get to run a country if you’re a suicidal fanatic.

No, the real risk is that of accidental launch. See “Counting to None”.

You can see this at work in the US Republican primaries, with the religious nuts being voted off the island. Even among self-selected adherents to the cause, there’s some recognition that babbling about Jesus and End Times is relatively harmless in a state governor, but not someone you want with their finger on the big red button.

Thank you.

The red queens race for security is amazing, iif you don’t crowd source you can’t get enough problem solvers to fix the problem, but if it falls into the wrong hands! Oh noez!

@all: One of the more worrisome things developing out of this situation is that it might be thought beneficial — by some — to have the intellectual and research community start policing themselves, and with that being generally dampening of the whole idea of “peer review”, having technology and research subjected by policing from the outside.

Sorry to mention Larry Niven once again, but I think he took a pretty good first whack at this with his short stories collected under “the Long ARM of Gil Hamilton”. “ARM”, the “Amalgamation of Regional Militia”, a sort of global UN police force, finds itself necessarily in the business of not merely regulating and safeguarding extant technologies — Mr Niven posits the development of a fairly inexpensive and compact fusion power generation system, about as “low tech” as semiconductor technology as the basis of civilization, easily jiggered to overload with catastrophic results — but also to safeguard the status-quo against any emergent technologies.

Mr Niven having attracted many critics who also write science fiction, some of whom he has allowed to write in a licensed shared-world mode, we’ve got a lot of fun stories about how the ARM went so far as to start with social and human engineering, trying to perfect humanity simply because it was actually easier than policing all technological innovation. And having engineered humanity into perfect little sheep, they’re not well equipped to deal with the Kzinti. 😉 Furthermore they’ve suppressed (and/or destroyed) all records from the time when humanity would have been equipped to deal with Kzinti.

But someone is going to have to oversee any future in which any hormone-crazed adolescent can mail-order the equipment needed for manipulating the polymerase chain reaction and automatically sequencing anything in the instruction set. Doting parental units might think “how cute, Junior’s growing up” when they see a line on the bank statement about “Home Cloning Kit Mark IV, Genuine Cindy Crawford Samples Included + FedEx Shipping” but unfortunately they don’t know that Junior is dabbling in politics as well, and has gone all ideological along lines that are best lest undisclosed as the plot elements of as-yet-unwritten SF.

Does anyone remember that stock character of the brilliant kid doing high-school work at age 11, runs down to the hobby shop for a chemistry set, wins the county Science Fair, and is never heard from again until apprehended a few years later pursuant to a rash of exploding high-school toilets?

Perhaps we might concern ourselves with this, at least as much as we concern ourselves with politicians, armies, and adult revolutionaries.

@anony mouse: A good point, that about the wartime conditions propagating the Spanish Influenza. But it wasn’t just that. My mom was researching genealogy and reviewed at lot of newspapers in that time-frame; public health authorities quickly realized that all public gathering places had to be shut down. That included schools, theaters, and market-places. And keep in mind, please, that the crowded conditions so conducive to infection, which at the time were mostly restricted to military barracks and the trenches on the battlefield, are now writ large upon entire landscapes, as high-density housing, mass transportation, and so many other characteristics of modern cities.

Thomas, my major point about war time conditions contributing to the Spanish flue had less to do with the barracks and trenches than with the secrecy that hid the fact of the flu due to fears of presenting weakness. If the fact of the flu had been made public, the mortality rate would have been much lower.

I think we, as a civilization, are already past a point when a bunch of folks or even a single actor can do immense damage.

Consider a suicidal individual with some kind of homicidal radical agenda.

Could he become an airline pilot? Yes.

Could he neutralize the second pilot and lock himself in the cockpit ? Seems not unlikely.

Could he then steer the vehicle into the largest building in the nearest city, essentially pulling off a totally homebrew 9/11 ? Yes, likely he could.

Or consider that crazy fucktard Brevik, who did remarkable damage without invoking any sophisticated equipment at all.

We appear to be generally very very vulnerable, and it might be that “OMG superviruses” aren’t the greatest vulnerability even if they happen to be relatively easy to engineer…

The mortality rate given in the post for the 1918 flu is incorrect. The reference here, http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/12/1/05-0979_article.htm#r3, states that 500 million were affected. From that, 50 to 100 million deaths means a 10% to 20% mortality rate. The 3% figure might come from the “case-fatality rates” which depends upon the sample size and seems to be referring to the entire human population at that time. So 3% of the world died, but the mortality rate was much higher.

The post should be changed to reflect the proper math lest it lend dishonest hysteria to an important issue, about which it is essential to remain clear-headed.

Actually, it turns out that mortality rate may not mean what I thought it meant, but it remains misleading statistic, and the much more digestible number of 10% to 20% of those affected dying from the disease remains supported by the numbers.

in relation to mortality rates, one purely linguistic question – when you say ‘to decimate’ (decimation of this or that population having been mentioned above a bunch of times), do you take it to mean ‘to reduce to one tenth of the previous number’? I had always understood it so, until someone pointed out that what it actually meant originally is ‘to reduce by one tenth’ – thus, something with a mortality rate of 10% would decimate the population. Something with a mortality rate of 75% …….. needs a bigger word.