The Heinlein Hormone

You all remember Starship Troopers, right?

That slim little YA contained a number of beer-worthy ideas, but the one that really stuck with me was the idea of earned citizenship— that the only people allowed to vote, or hold public office, were those who’d proven they could put society’s interests ahead of their own. Heinlein’s implementation was pretty contrived— while the requisite vote-worthy altruism was given the generic label of “Federal Service”, the only such service on display in the novel was the military sort. I’ll admit that thrusting yourself to the front lines of a war with genocidal alien bugs does show a certain willingness to back-burner your own interests— but what about firefighting, or disaster relief, or working to clean up nuclear accidents at the cost of your genetic integrity? Do these other risky, society-serving professions qualify? Or are they entirely automated now (and if that tech exists, why isn’t the Mobile Infantry automated as well)?

But I digress. While Heinlein’s implementation may have been simplistic and his interrogation wanting, the basic idea— that the only way to get a voice in the group is if you’re willing to sacrifice yourself for the group— is a fascinating and provocative idea. If every member of your group is a relative, you’d be talking inclusive fitness. Otherwise, you’re talking about institutionalized group selection.

Way back when I was in grad school, “group selection” wasn’t even real, not in the biological sense. It was worse than a dirty phrase; it was a naïve one. “The good of the species” was a fairy tale, we were told. Selection worked on individuals, not groups; if a duck could grab resources for herself at the expense of two or three conspecifics, she’d damn well do that even if fellow ducks paid the price. Human societies could certainly learn to honour the needs of the many over the needs of the few, but that was a learned response, not an evolved one. (And even when learned, it wasn’t internalized very well— just ask any die-hard capitalist why communism failed.)

I’ve lost count of the papers I read (and later, taught) which turned a skeptical eye to cases of so-called altruism in the wild— only to find that every time, those behaviors turned out to be selfish when you ran the numbers. They either benefited the “altruist”, or someone who shared enough of the “altruist’s” genes to fit under the rubric of inclusive fitness. Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene— which pushed the model incrementally further by pointing out that it was actually the genes running the show, even though they pulled phenotypic strings one-step-removed— got an especially warm reception in that environment.

But the field moved on after I left it; as it subsequently turned out, the models discrediting group selection hinged on some pretty iffy parameter values. I’m not familiar with the details— I haven’t kept up— but as I understand it the pendulum has swung a bit closer to the midpoint. Genes are still selfish, individuals still subject to selection— but so too are groups. (Not especially radical, in hindsight. It stands to reason that if something benefits the group, it benefits many of that group’s members as well. Even Darwin suggested as much way back in Origin. Call it trickle-down selection.)

So. If group selection is a thing in the biological sense, then we need not look to the Enlightened Society to explain the existence of the martyrs, the altruists, and the Johnny Ricos of the world. Maybe there’s a biological mechanism to explain them.

Enter oxytocin, back for a repeat performance.

You’re all familiar with oxytocin. The Cuddle Hormone, Fidelity in an Aerosol, the neuropeptide that keeps meadow voles monogamous in a sea of mammalian promiscuity. You may even know about its lesser-known dark side— the kill-the-outsider imperative that complements love the tribe.

Now, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Shalvi and Dreu pry open another function of this biochemical Swiss Army Knife. Turns out oxytocin makes you lie— but only if the lie benefits others. Not if it only benefits you yourself.

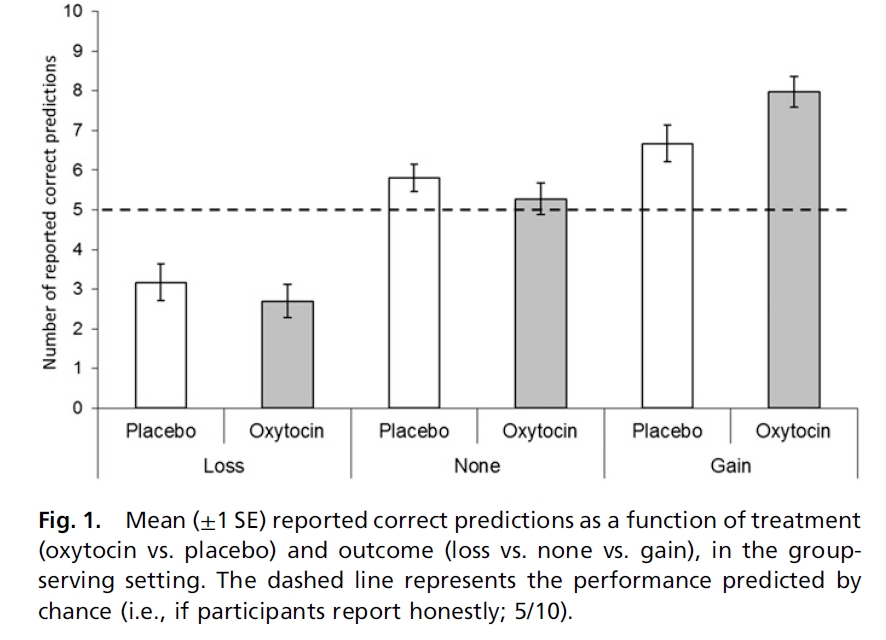

The experiment was almost childishly simple: your treatment groups snort oxytocin, your controls snort a placebo. You tell each participant that they’ve been assigned to a group, that the money they get at the end of the day will be an even third of what the whole group makes. Their job is to predict whether the toss of a virtual coin (on a computer screen) will be heads or tails; they make their guess, but keep it to themselves; they press the button that flips the coin; then they report whether their guess was right or wrong. Of course, since they never recorded that guess prior to the toss, they’re free to lie if they want to.

Call those guys the groupers.

Now repeat the whole thing with a different group of participants— but this time, although their own personal payoffs are the same as before, they’re working solely for themselves. No groups are involved. Let’s call these guys soloists.

I’m leaving out some of the methodological details because they’re not all that interesting: read the paper if you don’t believe me (warning; it is not especially well-written). The baseline results are pretty much what you’d expect: people lie to boost their own interests. If high predictive accuracy gets you money, bingo: you’ll report a hit rate well above the 50:50 ratio that random chance would lead one to expect. If a high prediction rate costs you money, lo and behold: self-reported accuracy drops well below 50%. If there’s no incentive to lie, you’ll pretty much tell the truth. This happens right across the board, groupers and soloists, controls and treatments. Yawn.

But here’s an interesting finding: although both controls and groupers high-ball their hit rates when they stand to gain by doing that, the groupers lie significantly more than their controls. Their overestimates are more extreme, and their response times are lower. If you’re a grouper, oxytocin makes you lie more, and lie faster.

If you’re a soloist, though, oxytocin has no effect. You lie in the name of self-interest, but no more than the controls do. The only difference is, this time you’re working for yourself; the groupers were working on behalf of themselves and other people.

So under the influence of oxytocin, you’ll only lie a little to benefit yourself. You’ll lie a lot to benefit a member of “your group”— even if you’ve never met any of “your group”, even if you have to take on faith that “your group” even exists. You’ll commit a greater sin for the benefit of a social abstraction.

I find that interesting.

There are caveats, of course. The study only looked at whether we’d lie to help others at no benefit to ourselves; I’d like to see them take the next step, test whether the same effect manifests when helping the other guy actually costs you. And of course, when I say “You” I mean “adult Dutch males”. This study draws its sample, even more than most, from the WEIRD demographic— not just Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic, but exclusively male to boot. I don’t have a problem with this in a pilot study; you take what you can get, and when you’re looking for subtle effects it only makes sense to minimize extraneous variability. But it’s not implausible that cultural factors might leave an imprint even on these ancient pathways. The effect is statistically real, but the results will have to replicate across a far more diverse sample of humanity before scientists can make any claims about its universality.

Fortunately, I’m not a scientist any more. I can take this speculative ball and run with it, anywhere I want.

As a general rule, lying is frowned upon across pretty much any range of societies you’d care to name. Most people who lie do so in violation of their own moral codes— and those codes cover a whole range of behaviors. Most would agree that theft is wrong, for example. Most of us get squicky at the thought of assault, or murder. So assuming that Shalvi and Drue’s findings generalize to anything that might induce feelings of guilt— which, I’d argue, is more parsimonious than a trigger so specific that it trips only in the presence of language-based deceit— what we have here is a biochemical means of convincing people to sacrifice their own morals for the good of the group.

Why, a conscientious objector might even sign up to fight the Bugs.

Once again, the sheer abstractness of this study is what makes it fascinating; the fact that the effect manifests in a little white room facing a computer screen, on behalf of a hypothetical tribe never even encountered in real life. When you get down to the molecules, who needs social bonding? Who needs familiarity, and friendship, and shared experience? When you get right down to it, all that stuff just sets up the conditions necessary to produce the chemical; what need of it, when you can just shoot the pure neuropeptide up your nose?

It’s only the first step, of course. I’m sure we can improve it if we set our minds to the task. An extra amine group here, an excised hydroxyl there, and we could engineer a group-selection molecule that makes plain old oxytocin look like distilled water.

A snort of that stuff and everyone in the Terran Federation gets to vote.

Can you recommend a popular science book like ‘The Selfish Gene’ but covering group selection?

I’m doing my part!

@ Mike G. – you might try E.O. Wilson’s The Social Conquest of Earth.

I actually think that, while it was a brief mention, Starship Troopers does explicitly mention non-military service careers. It is just that the military careers are the most glamorous and result in the better connections.

They also explicitly state there are R&D paths within the military option as well.

Pedantic, but I seem to recall mention of not everyone getting military service in Starship Troopers; it was just the most common because, well, war against giant bugs.

Are you sure about group selection? Evolution may well favour individuals who are inclined to work in groups, but that’s not at all the same thing as group selection. Among the many problems with the idea is the reality that new groups are spawned much less frequently than new individuals, so there just isn’t very much opportunity for evolution to work at the group level. It’s not as if German society died in, say, 1870 and left its offspring societies to compete with whatever descendants France left behind.

I found The Social Conquest of Earth worth the read, but most of it isn’t about group selection. On that subject, you might want to read Richard Dawkins trashing Wilson in Prospect magazine:

https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/edward-wilson-social-conquest-earth-evolutionary-errors-origin-species/#.Uz4h3PldWT8

Building on that idea, theoretically, we could create chemically controlled/induced soldiers or assassins. There could also be a market for people who want to chemically control their fidelity with their partners. Plenty of hive based insects do this kind of thing on many levels.

Be interesting to see if humans could pull it off. Though it does seem like the more we try to improve, the more we tend to fuck up our species.

I haven’t read Starship Troopers in awhile, but I do remember that there were a couple references, early in the book, to non-military federal service. It’s not heavily emphasized (and if I recall correctly, military service was much shorter than the alternatives) but then again why would it be? It’s titled Starship _Troopers_ after all, not Starship Federal Service. It’s the story of a boy who joins the military and becomes first a man and then a leader.

Your confusion might arise from the book using the word “veteran” generically, which even back then (1959) was strongly associated with the military. Heinlein went on the record about that (veteran not equaling military) in his anthology Expanded Universe.

As a side note, Starship Troopers was written as a juvenile, but the publisher wouldn’t publish it. It was later published as an adult book.

Group selection is certainly not impossible. It just requires some precise parameters which area rarely found in nature. Consider the naked mole rat, an animal which became eusocial despite not having the chromosomal system characteristic of hymenoptera.

However rare it may be in nature, it is trivial to create in the lab. This post uses such an experiment as a warning against letting human aesthetics interfere with your assessment of nature.

Which reminds me of something I thought years ago as a result of that post which I had never gotten around to telling you. Some time after I read that post, it abruptly occurred to me one day that a similar criticism could be leveled against a remark you once made about the size of the human penis being proof of human women being sluts. Which is, “…or of the prevalence of gang rape.”

One hole to take a jab at with your theory:

Aren’t you disregarding the individual’s internal wiring here when you say that oxytocin or oxytocin-functionalgroup would necessarily cause adherence to some massive social norm? I don’t see why the conscientious objector’s feelings *aren’t* their idea of group selection, unless you are casting aspersions on the intentions of a “conscientious objector” Vietnam war draft dodger and saying he may just want to save his own skin (which, of course, may be the case).

Imagine that the objector instead believes fighting the war is actually strictly against the well-being of his own people (whatever that defintion may be). A much less likely example is that he truly *does* perceive the ascribed enemy as no different than his own group, which doesn’t make sense with bugs, but might make sense in bloods vs. crips. I imagine such a drug would improve your overall recruitment numbers, but you’re assuming everyone’s hardwired like mole rats. I’m wondering if a few extant members of society are more like Jesus, and your Oxytocin love-the-group makes their love-everyone instinct even higher.

Obviously this beggars optimism, but you may see my gist. Actually, in retrospect, I see the obvious conclusion: If someone is dosed to the eyeballs and still doesn’t choose Big Brother’s group over East Oceania, they’re headed straight for the “reeducation camps”. And we do know what they did to Jesus.

Damn. I guess your drug works better than I thought.

AR+: You make an excellent point.

Hmm. The first thing that springs to mind is that the social model as paraphrased from Heinlein is no “opt-in democracy”, but more some kind of fluid aristocracy. I mean, if you have to fight in a war before you may vote for the ending of said war – this is the superlative of “taxation without representation”

As for the experiment, as interstig as it may be – the whole situation is one were the subjects don’t do what humans do all the time – communicate. So I I don’t think this experiment tells us much about the behaviour we show in the wild.

Re communication Even alone, we think in categories we learned from others. So I think Paul touches the correct point with his consentious objectors – One may well think that dodging the draft or even, once enlisted, fragging ones officer, is the best for the nation or whoever is the relevant group. A matter of choices, ideology, chance.

But: I think it’s misguided to talk about this in the term of “wiring”. I mean, ultimatly it comes down to wiring and hormones, no mistake, but we are so, so far away from actually understanding said wiring …

For the foreseeable future, we should stick to talking about society in the terms of the sociologist. Explaining actual human behavior soleyly with neurons and hormones is like drawing a graph and leaving pout the error bars.

Dear Peter–

This does not really belong here, but the military law comments are closed and I could not figure out any way to mail it to you directly. Should have checked before I wrote it. Sorry.

I found the argument concerning consciousness in Blindsight every bit as disturbing as I think you hoped. And I think that you are right that the best current evidence suggests we make most decisions well before we are conscious of them, so that that our consciousness does not control our actions in the way we like to suppose. Indeed, we have even more direct evidence. People who have had frontal lobotomies appear human — and would pass the Turing test — even though they have lost most if not all of their capacity for self-reflection and self-observation.

But I do not think this implies that our consciousness does not affect our actions. Just as one event being after another does not imply the the latter is caused by the former, so also, causes can follow effects, at least in systems that can predict the future, consciously or otherwise. Rain in the afternoon causes umbrellas to be carried in the morning, and not conversely. Or, closer to the mark, tax auditors always come after the decision to cheat or not to cheat has been made. Does that imply that they have no impact on that decision? It does not. Our consciousness provides a part of the environment that our decision-making system has evolved with and in. The part of our minds Daniel Kahneman calls “the fast system” anticipates pain and pleasure as much as it anticipates trajectories of a ball we catch. And this includes the pain and pleasure of our conscious selves being pleased and displeased by what we have done.

This has the rather disturbing implication that _Guilt_ may be the most important function of consciousness, at least as it affects our decisions. Guilt, much reviled and often claimed to be dispensable, is the auditor that comes after immoral (or merely imprudent) choices and makes us regret what we have done. And the fast system can anticipate that emotional pain, doesn’t like it, and avoids it when the drives and motives evolution has hardwired it to attend do not outweigh it. (And it turns out that, empirically, regret-minimization is as good or better than Kahneman & Tversky’s prospect theory in explaining the peculiarities of human behavior under risk, and seems to be generally superior in explaining why we behave differently when objectively identical outcomes are framed as gains as versus avoided losses (or losses as versus missed opportunities for gain).

I think this has an interesting implication for your military story. When the defense contractors who designed and built this targeting and triggering mechanism set out to calibrate it to the actual decisions of specific soldiers, what sort of training data (in the “machine learning” sense) did they use to calibrate its predictive systems? Real decisions to kill civilians would be very expensive to collect, and a soldier’s knowledge that hes behavior and mental states were being constantly observed would tend to deter even the Lt. Calley’s of the world. A properly cost-conscious defense contractor would be unlikely to amass a huge amount of such data. I suggest that, instead, they calibrated the system with a soldier’s brain states and choices in virtual war game training simulations.

Now, if these simulations were designed by the army and used to prepare soldiers for battlefield readiness, one presumes there would be points deducted for injuring simulated civilians. But these point costs might be outweighed if the decisions improved the soldier’s chances of mission success. And so long as the soldier remains aware that these are simulations, true moral judgements, and guilt over bad moral decisions, do not come into play. In his Confessions, Augustine says that we are morally responsible only for our actions, not our experiences, and that we therefor can not do evil in a dream. A soldier would learn to make decisions based on how they are evaluated, not by their moral intuitions. The the soldier’s fast system ends up calibrated against, not the guilt felt by a conscious murderer, but the point system of the war game simulation. The result is that your hyper-fast battlefield weapons system will have been trained to the simulation point system, not to conscience. Or so a clever defense attorney might argue. (And if this whole line of reasoning is unsuitable to your plot, you can avoid it if you can provide advances in simulation technology that can make a soldier unaware that their experiences are not real).

Of course, sufficiently realistic simulations may be training the soldiers own “instinctive” battlefield decisions to the same point system.

Here is a final conundrum for you, not directly connected to your war story plans. We know from, e.g. the split-brain experiments that our conscious minds almost always come up with, and believe, stories that explain what we have just done, even when those stories are quite implausible and actually false.

Suppose one could cut off the feedback from consciousness to the fast system altogether, and put something else in the place of that feedback — some set of artificial guilts and goals as powerful as our conscious ones, but not originating from within. But suppose that all the input feeds to our forebrain are not destroyed, but rather maintained active and in place. The notion is that our consciousness would not be not in the driver’s seat, but would most definitely and completely be along for the ride. What would that do to us as moral creatures? Would it merely eliminate moral concerns as delusory? Would we immediately know that we are no longer in charge? Or would we, over time, revise our stories to fit our behavior, and come to be the moral creature that we observe ourselves to be?

How much time would that take, do you think?

What happens if you’re taken off the oxytocin supplement? Do all your new friends suddenly seem like phonies, because they don’t deliver the same high they did when you were getting the supplements? Maybe subjects would be permanently dulled against getting attached to other people the “natural” way.

Or to steal someone else’s spouse…

Or to seal radical support for someone’s favorite leader. Imagine millions of chemically-induced Palin supporters.

I took an instant dislike to this hormone the very first time I heard of it (it was in an article about how it hacks mothers to coo lovingly and fawn all over their mewling newborns… responses that are vital and which I have nothing against… I just hate the molecule for reminding us that the responses in question needed to be induced at all – not all that surprising though. I also, in that same context, disliked it for being implicated in yet another women are controlled by hormones meme. *roll eyes*).

Nothing I have subsequently read has warmed me up to it.

Bleurch.

Be gone, Oxytocin. Be gone with twiddly little knobs on.

@Leona: I’m not sure what you mean by “induced” – you seem to believe that said motherly love could exist without hormones, but as far as I understand it, those hormones are what constitutes motherly love in the biochemical system.

Your periodic quasi-off topic link interruption:

Study on skin cream and math converts to politics and how more facts won’t cure stupid nor partisanship. Also contains funny anecdote about how Hannity could ruin his career by jumping on climate change wagon.

http://www.vox.com/2014/4/6/5556462/brain-dead-how-politics-makes-us-stupid

Something about DRM and digital libraries involving Watts, Mieville and other hombres/hombrettes

http://www.lacasadeel.net/2014/03/literatura-de-genero-y-libro-digital.html

Oh dear. “Lying is frowned upon.” This is a lie, which you are expected to affirm or there will be consequences. If something occurs which uncovers a lie, you are expected to help cover it up. Whether or not the system works, whether or not the system is fair and just, above all else and before anything else everyone must affirm that it is all of these things and that this is the truth.

Can I highly recommend the book “Domination and the Arts of Resistance”?

http://www.annleckie.com/2013/07/11/92/

Leona,

Who’s to say men are not controlled by hormones? 😉

Thing is, compared to most other apes, HSS shows few sexual dimorphism, and I know quite a few cases of child-induced pseudodementia, err, in males. 😉

martin,

“Hmm. The first thing that springs to mind is that the social model as paraphrased from Heinlein is no “opt-in democracy”, but more some kind of fluid aristocracy. I mean, if you have to fight in a war before you may vote for the ending of said war – this is the superlative of “taxation without representation””

No. The book specifically mentions public protests that got the government to change course. It is the demonstration in response to showing off the genetically enhanced dogs for the K9 military units. There is also a mention of protests after the attack, but not that the government cowed to them.

Also, you don’t need to fight a war. The book mentions pilots, police, scientists, and terraformers as other options, and offers up absurd examples of counting hairs on a caterpillar by touch as an example of how far it can stretch.

Also, the standard non military but rich plutocracy still exists running the show. Rico’s father is one of them – has a slot reserved for his son at Harvard already to ensure he makes the right connections. In the grim darkness of the far future, Cash Rules Everything Around Me.

That was my first thought as well. I suppose it could induce even more selflessness because you’d be chasing the high, though. Like, you have to help others more to get the same neurochemical reward, so it’s like any drug.

Personally, I’m somewhat sceptical about group selection; most of the “altruism” we see can be explained by inclusive fitness or mutualism, also note evolution is never perfect, and while there might be cases we can perceive genes, e.g. the greenbeard effect or the MHC smell association, in most cases it’s likely to boil down to a good heuristics, e.g. “protect eggs in my nest” etc. So some of the things that look only explainable by group selection might in fact be effects of “family selection”, e.g. inclusive fitness, from a time we lived in in small family groups.

Of course, there is also the funny things humans create out of the good old mammal ethological programs…

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinship_terminology

For the original paper, well, first of humans using different ethical standards for individuals and groups (may we include “corporate personhood as an example for the latter?) is not that surprising, also note the things states can get away with under international law, making you wonder sometimes if holding it up or braking it is worse…

Second of, there are some alternative explanations I’m not that sure they’re mentioned; maybe the participants were not that much lying, but really correctly predicted the results, it has been known to happen with faulty RNGs before. A somewhat more tricky issue would be the conditions interacting with short term memory, again with multiple subissues, as an example, maybe the oxytocin group in the group experiments was somewhat occupied with thinking about the Greater Good(tm), which made for them forgetting the prediction they made. Now humans have this strange idea of assuming “just as planned” no matter the outcome, which might be a general problem with this setup, so they fill in “correct answer” or “incorrect answer”. Which would not necessarily be a lie, if you can’t remember the original answer.

Of course, the experiment rewarding not just correct but also wrong predictions would make the first possibility somewhat suspect, though it might not apply that much to the “faulty memory” alternative.

Oh, and third of, one of the funny things happening when Germany still had conscription were the personal talks you were sometimes subjected to when objecting; seems like “you’re in a wood with a gun, and somebody is raping your girlfriend” was a standard question, though the personal talks got mostly tossed in the 1980s.

Please note that you still did “Zivildienst” in hospitals and like (though there were some absolute objectors), and, well, you usually did this or military service before the vote. 😉

“Does money make you mean?”. It’s amazing what a rigged game of Monopoly can reveal. In this entertaining but sobering talk, social psychologist Paul Piff shares his research into how people behave when they feel wealthy. (Hint: badly.) But while the problem of inequality is a complex and daunting challenge, there’s good news too.

https://www.ted.com/talks/paul_piff_does_money_make_you_mean

Paul,

actually, i wouldn’t be that surprised if there were quite some people around like jesus, i’m just not that sure it’s fun to be around them.

you see, if i try to imagine jewish culture at the time, the result has quite some similarities with the current islamic world. and the best model that comes for the guy is a moderate islamist. though in the end, he failed the game.

personally, of the whole posse i have a soft spot for simon petrus, while he didn’t break with his culture like paulus did, he was quite, err, shrewd. and managed to stay alive a lot longer. you might excuse my little ideosyncrasy there.

on a more general level, i have some problems with this “pure founder, degenerate fellowship” issue, you just have to look at the mormons to see this is not necessarily true. sometimes i though about writing about a petrus expy, call it “the disciple”, may even coming up with the idea of the “two natures of christ” to explain away his master’s more nasty moments…

Regarding group selection, I always figured the following reductio ad absurdum: If you are a dodo and someone brings rats to your island, your group’s gonna get selected against. Ergo, group selection exists. At least in extinction level edge cases… and maybe here and there in other contexts

Pirmin,

My point exactly 🙂

Daniel Gaston,

Heinlein was also a military man, tho one that never saw any actual combat.

I’m kinda worried by the spectrum of roles oxytocin plays in humans.

Using same type of signal to achieve a whole number of different outcomes based, seemingly, solely on signal parameters and context, is usually a poor design, often resulting in exploitable vulnerabilities (And everything that can be “hacked”, eventually will be “hacked”)

I come from a society where misrepresentation, corruption and lying (without getting caught, of course 😉 ) are more or less accepted as inalienable parts of a successful life.

And no, it’s not an island in the middle of the pacific.

Funny thing is, you can find somewhat similar ideas to Heinlein’s in quite some writers you wouldn’t expect. Would be funny them meeting each other, BTW.

Take, for example, one Peter Kropotkin; in “The Conquest of Bread” you find this:

Actually, IMHO this is easier to conceptualize along the lines of mutualism or maybe a gift economy than group selection, but whatever.

Could be funny to quote this one to some anarchists/libertarian socialists I know…

Not a book, but if you do a google on “scienceblogs” AND “group selection” you/ll get a whole bunch of entries from the science-blogs forest, covering both the theoretical rehabilitation of the concept and the political controversy raised thereby.

Maybe the easiest way out of the entrenched corners everyone has dug themselves into is to just do away with the term and slot in the more-inclusive :”multilevel selection” instead.

God no. I’ve been out of the field far to long to pretend to that level of expertise. All I can say is that the concept, once thoroughly discredited, seems to be making a comeback, and said comeback is not happening at the hands of flakes; very credible people are taking up positions on both sides of the argument.

That was interesting, thanks. Have you seen (a different) Wilson’s response to Dawkin’s critique on a (different) iteration of (the same) issue?

http://scienceblogs.com/evolution/2010/09/04/open-letter-to-richard-dawkins/

Like I say, I’m not competent to judge. But science itself is predicated on aceptance of the premise that everything we believe is subject to potential disproof, and it’s heartening to see this debate in that light. It suggests that the system works.

I don’t think Starshiptroopers about altruism. It’s much bigger about initialization ritual. Only way be full-grown in Terran Federation is service in army. If you don’t service at army you just a kid for all your life. And your federal “daddy” can punish you if he want, because you just a kid.

All Terran Federation basic on this methapor.

Hey, Peter,

Very interesting post and fascinating study. I became interested in oxytocin while researching PSSD, post SSRI sexual dysfunction. Several studies demonstrated that it was a promising therapy, but as a practical matter, one of the problems with intranasal administration is that the half-life is really short, like about three minutes. To paraphrase Jack Margolis (“A Child’s Garden of Grass”) this is kind of like hiding your reefer by throwing it way up high– it works well, but for a very short period of time.

As a therapist who finds biological psychiatry ludicrous and horrifying, I’m appalled by the gross generalizations about neurotransmitters which find their way into popular culture. Yeah, sure– Dopamine causes pleasure, serotonin cures depression, and oxytocin is the cuddle hormone! What a pile of crap. Thanks for the breath of fresh air.

Maybe the pendulum will swing the other way, and people will start referring to oxytocin as “The Bullshit Hormone”. The next question is, if oxytocin can make you a liar to serve your (sometimes hypothetical) group, can it make you a BETTER liar? GlaxoSmithKline will probably develop some ghastly knockoff designed for marketing executives.