The Gene Genies, Part 2: The Genes that Wouldn’t Die.

Evolution with Foresight: an oxymoron, right? Evolution has no foresight. Natural selection only promotes what works in the moment. If a particular mutation doubles your reproductive rate, you will fill the world with thy numbers; the process doesn’t understand too much of a good thing, doesn’t care if greater fecundity today means overpopulation, starvation, and extinction tomorrow. All it cares about is whether the latest edit gives you an edge right now. Natural selection is the very incarnation of instant gratification (which, I’ve always thought, explains a great deal about human stupidity.)

But what if we could build foresight into the system? What if we could build a gene for— I dunno, say reduced fertility, give the biosphere a break— and let it loose in the human population? Obviously it would go extinct; people with that gene would breed less, the rest of us would breed more, and a few generations down the road you’d be right back where you started.

But what if— what if— you could force that gene onto the next generation, even if it reduced fitness in the classic sense? What if you could build code that would be beneficial over the long term, and ensure its spread even if it costs you in the moment? What if we could gift evolution with foresight?

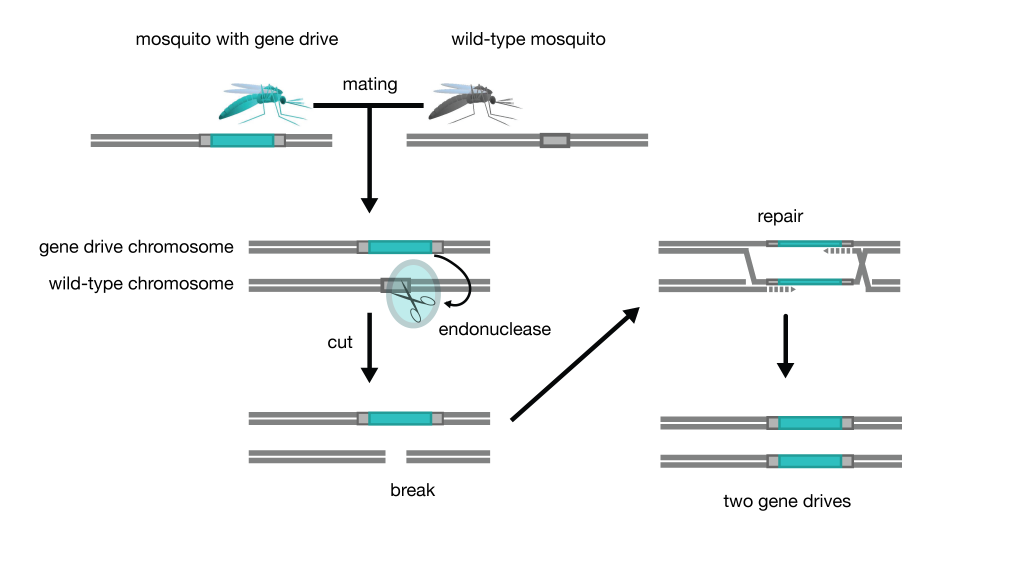

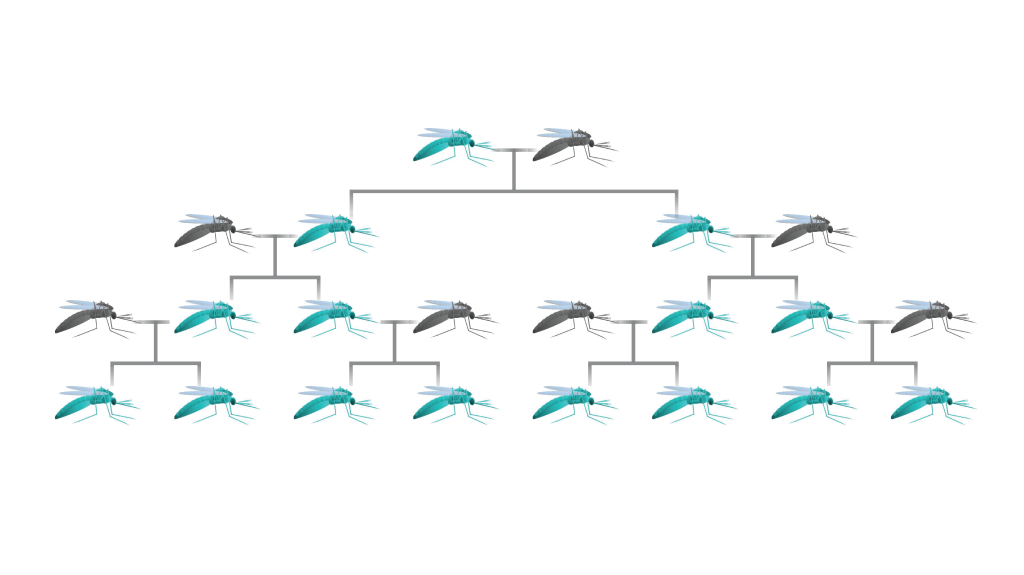

Enter the Gene Drive, CRISPR/Cas9 for short. It’s a clever little machine built of enzymes and RNAs, and you can attach it to pretty much any gene you like. When a gamete from your transgenic organism hooks up with one from a baseline, CrisperCas detects the presence of the competing wild allele, cuts it out of the opposite strand, and splices your engineered code into the gap. It overwrites wild genes with engineered ones, turns heterozygous pairings homozygous. You can see how this would stack the odds.

And introducing engineered, virtually-unkillable genes into wild ecosystems to do our bidding?

What could possibly go wrong?

CrisperCas flew right under my radar when Esvelt et al took it on tour last summer (I was too distracted birthing Echopraxia). Fortunately this month’s piece in h+ got me up to speed, providing links to some of those earlier articles (also here and here). To do them credit, CrisperCas’s advocates admit that their technology has the potential to “alter ecosystems … so we’ll have to be very careful not to cause damage accidentally”. If that’s not enough assurance for you, Oye et al have also put out a piece in Science admitting that “Scientists have minimal experience engineering biological systems for evolutionary robustness”, and urging us all to get our ducks in a row before we start fiddling with their genes at the population level. They advocate extensive public consultation, careful risk management, and scrupulous regulation to make sure that nothing goes wrong. They introduce something called a “reverse drive”, which can be called upon when something inevitably does. (Reverse drives seem to be basically another iteration of the gene drive, configured to undo what the last one wrought. I’m thinking a better name might be “The Little Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly Drive.”)

As Esvelt and his buddies point out, it would take centuries to engineer human populations this way; we large mammals are relatively slow breeders. They’re much more excited about inflicting the tech on other pest species; disease-carrying mosquitoes, for example, or crop-eating beetles whose resistance to the usual pesticides might be undone by gene drives. But I’m looking even further down: down past the insects, the protists, even the bacteria. I’m remembering that line from Dawkins— life is information, shaped by natural selection— and my recurrent musings (admittedly less cutting-edge now than they once were) that life can be built from ones and zeroes as easily as from carbon and nitrogen. Hell, if you buy into digital physics, that’s all any of us are anyway.

Natural selection with foresight. It could change the world even up here, albeit slowly. Think of what it could accomplish in your smart watch.

I wonder if this has anything to do with how the Maelstrom gets started…

“Natural selection with foresight”. As in “Intelligent Design”? >_<

CRISPR/Cas9 would make a nifty bioterrorism device if you were prepared to think long- term. Imagine the ransom note: “Fork over the fifty mil now, or the human race gets it … about four hundred years from now.”

“What could possibly go wrong?”

I seem to remember the beginning of Echopraxia covering Bruks musing about his hopes of ever finding actually natural wildlife even in the ass end of nowhere. Even as you are writing SF, science is happening in close parallel, possibly a sign of good hardscience SF writing. As to the matter of population control, this reminds me a bit of Philip Jose Farmer’s “70 Years of DecPop” or the Cuarón film “Children of Men”. Of course, that would be morally questionable at best… but if you want to counter Bat Population Decline by engineering a matching decline in mosquitos, you might find a lot of moral support from itchy people everywhere.

Yet the “reverse gene-drive” notion holds out some hope of controlling “the monsanto-izing of nature”, though there would have to be some intentional effort to disperse a lot of diversity of genes sent out to replace the corporate versions, or you get just a different monoculture, if not enough natural variation remains in the “natural” pools.

Peter, you set the timeline for “Blindopraxia” some 70 or so years from now, which some people might think is too brief a time for the world to so greatly change. But do you ever get the feeling that it could be starting to happen a lot faster even than that?

How sure are we that something like CrisperCas cannot cross over to other species? Could it jump into a frog population or some other species that has close contact with mosquitoes?

Let’s just say I’m not ruling it out.

This is my constant experience. A lot of the stuff I predicted for 30, 40 years down the road in Starfish are already happening. Some of that stuff started happening before the book even reached the shelves.

My gut also tells me that Blindsight is set too near in the future for all that change— but experience suggests that if anything, I set it too far.

Not so much mosquito to frog as mosquito-to-some-other-Culicid-insect, but yes: gene drives going walkabout in closely-related species is one of the issues they raise.

Passing thought re “reduced fertility.” Ah, The Handmaid’s Tale.

More lingering thought, gene-terror, where virii get spread that alter appearance of breeds of pets popular with celebrities. Glow in the dark, scaly chihuahuas with skunk scent or something in a future when all restaurants are Taco Bell.

More to the point of the first paragraph, this implies squiddies went through some interesting challenges and survived them. You may not be as close to the cutting edge as you were, but I think some of us are wondering what the changes can actually do for the squid and as someone asked in the Part 1 thread, can adult squids still do this, and if the papers’ authors have any idea about those things.

As long as we are taking Margaret Atwood books, how about “Oryx & Crake” or “Year of the Flood.”

What is (directed, controlled) gene manipulation if not intelligent design :).

Even if natural selection does not have foresight, I think it has enough dampening to promote things that works well in the longer run throughout changing environments even if it’s not optimal at any given point in time. Be to optimized for now and the slightest variation might kill you off.

(There seems to be a bit of a name collision here. This is derailing-of-threads-markus from last week.)

/Markus(2)

Darwin called it “Methodical Selection.”

Also Mr Watts! You seriously need to work on your back catalog I want to give copies of books to people as gifts, not email them pdfs.

http://i1.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/facebook/000/264/200/acb.jpg

What foresight?

This is just unkillable gene, not foresight. Also, the machine, does it last forever?

Whut? Too much? Just right imo. What I found weird was absence of technological telepathy.

The first, last and only sensible use of this process should be to remove the gene(s) that affect the neurological development of scientists such that they find themselves to be compelled to tinker with nature.

Oxytricha trifallax laughs at such primitive self-modification.

And in homo sapiens we have LINE elements. We have already been engineered, to serve the needs of a retrovirus.

Quoting Peter Watts, responding to my question about timeframes in his fiction versus speed of technical advance in reality:

Here we run up against some constraints which I am not certain how to categorize. For example, Our Gracious Host is very much the same age as I am, and doubtless got exposed to Alvin Toffler’s thinking as in Toffler’s book Future Shock. A summary would be that “the Future” comes at us with increasing speed, leaving us with proportionately less time to adapt and internalize the changes.

Many people who read that book have internalized the notion that one of the few reasonable immunizations against Future Shock is reading good hardscience SF. Sometimes that works pretty well and sometimes less so. For example, if anyone read much Mack Reynolds back in the day, the second they even heard of the notion “internet” in the context of “cellphones”, they wisely invested in an industry destined to take over the world. Yet if they had invested in the notion of inevitability of technosocialism in a post-industrial economy of surplus, they would still be waiting on return from investment.

People need time to adapt, or at least most adults need time to adapt; children are born to adapt as part of the learning and maturation process. Yet how would we adapt, as individuals, or as societies? Clearly this is the main theme of SF in general. Yet Peter says, and I agree, that a lot of potentially massive change is now becoming technically feasible, and it’s happening faster than even SF writers guessed, and when will we have time to adapt? Take the timeline we see in Blindopraxia and track back the cat, so to speak. If Jukka Sarasti and Valerie are perhaps 25 years old, then if they matured at a human-normal rate, they would be popped out of their surrogate-mother or artificial-womb about 50 years from now, and one presumes that in this fictional universe there probably would have been a lead time of some 10 years at the least. So, in that timeline, Peter’s multimedia presentation on “taming yesterday’s nightmares for a better tomorrow” could be 40 years from now… or you might wonder if maybe they launched a larger project after about a short generation’s worth of a smaller project. In that case, subtract another 20 or so years… and if we were in fact headed down the path to Blindopraxia, that means that it wouldn’t be long at all before a select few find out that there are corporate labs with basement labs building, or already full of, what a lot of people might think of as scary monsters. Is anyone actually ready for this?

But that’s just one example out of this fiction. In Echopraxia, almost buried in the text, is a pharmaceutical referred to as “Cognitol” IIRC, and Bruks is unusual in that he takes his by mouth whereas everyone else has implanted dispensers. This may be one of the most revolutionary notions in the novel: that in the future, drugs are available and in common use, which enhance thinking ability to, or near to, a theoretical maximum. What would be the implications to society, if — for example — causes and cures were discovered for depressive disorders and the schizophrenia-class psychotic disorders? Or of other mental dysfunctions of all or most kinds? Suddenly everyone is, at a minimum, brilliant and sane, for varying definitions of such (see also “Bicameral Order”). What happens to the mental healthcare industry? Eldercare? Peter Watts shows us “Heaven”, but while it might be a likely alternative, is it the only one?

Or, really far more to the point, what happens to Futurism (especially when used as a guide to investment and social strategy) when the world changes faster than anyone can write a position paper? Does “Future Shock” get so out of hand that we can’t call it anything other than either Singularity, or as Gibson has it, “the jackpot”?

Fascinating !

However, I think that it all depends on how you define foresight.

Even simpleminded things like redundant genes could count as “foresight”. Doubly so for things like “having a bunch of redundant genes and upregulating mutation rate on some of them when a stressor arrives”.

P.S.:

In next installments of this series, you could take a look at Rotifers (which are basically IRL Tyranids) and “competent” bacteria

Whut?

Brilliant? Intelligence, most likely, dependent on brain structure, which can hardly be re-arranged just by taking some simple drug*. At least, not in the short or medium term.

*if we’re speaking chemicals or mixes of chemicals, not viruses and other machines.

They do speculate, a little. I just left a comment under the other post with the relevant quote.

Still haven’t read those (or “Maddaddam”). Haven’t read anything of hers since Cat’s Eye, which I thought was great.

Of course, if it’s genre you’re after, you’re not missing anything ’cause Atwood doesn’t write that stuff. She’s one hundred percent cootie free.

A perfectly legitimate way of looking at natural selection is by looking at persistence instead of abundance. Each generation, instead of asking “are your genes the most abundant?”, you ask “Do your genes still exist?”. As long as the answer is yes, you still have a rabbit to pull out of the hat the moment that gene becomes beneficial. Which, I guess, is an advantage of having a huge genotype, and another reason to feel inferior to onions.

Either way, though, there’s no foresight. The thing asking the question is pure metaphor.

I don’t know what you mean by this. Although I appreciate the sentiment.

I did not know about this guy. Thank you.

It’s actually not that revolutionary. Even last decade, 20% of working scientists surveyed by Nature reported taking some kind of brain booster to keep up with the Dawkinses. It doesn’t take a marine biologist to knew that— if academia as we know it even exists in fifty years— it’ll be populated by those who’ve optimized their own cortical circuitry in some way.

I thought of Rotifers, but AFAIK the whole facultative male thing isn’t recoded.

Then again, I bet no one ever looked to find out..

@Peter Watts: It’s actually not that revolutionary. Even last decade, 20% of working scientists surveyed by Nature reported taking some kind of brain booster to keep up with the Dawkinses.

Shades of Erdos and his bennies and ritalin! I guess that I could thus see that the whole Bicameral Order idea in Echopraxia might be an allegory on exactly this trend, a question of “what exactly are we willing to do to ourselves to get out on the cutting edge of science”? (I cannot use strong stimulants, myself, because they make me seriously crazy. Thus I could never compete in the sciences. 😉 )

More to the point of the original post, I think there’s huge potential for both speculation and applications of CrisperCas as a sort of novel antibiotic, pretty obvious there. But I see huge applications, as well, in things such as designing special organisms for fermentation-like processes for pharmaceutical production, etc. And if these get loose and do things that they shouldn’t? The reversing gene-drive. Though this has the potential to get at least temporarily out of hand, resulting in something like “toner wars” as in the Diamond Age. More likely to happen, and sooner, in my humble opinion.

Re: Peter Watts

I wasn’t talking about their weird “faculative sex” thing.

I was talking about outright gene-stealing.

Bdelloid Rotifers are capable of literally stealing genes of other (often utterly unrelated) organisms (and that way they both ensure genetic diversity that would otherwise be impossible in an asexual context, and that the genes that are part of this diversity are more likely to be environmentally relevant and functional than ones which one would usually arrive at through only random mutations)

http://news.sciencemag.org/evolution/2012/11/bdelloids-surviving-borrowed-dna

So yeah, they are a bit like Tyranids and Giger Xenomorphs that way – though (un)fortunately they don’t (yet) build fleshy spaceships or eerily suggestive hive-temples.

How did I miss this? 500 species!

This is definitely going into ID.

Isn’t that just ConSensus, though? If not telepathy, it’s awfully close.