A Mirror.

Spoiler Warning: pretty much this whole post, if you haven’t yet seen Ex Machina. Then again, even if you haven’t seen Ex Machina, some of you might want to be spoiled.

I know I would.

So. In the wake of that slurry o’sewage that was Age of Ultron, how does Ex Machina stack up?

So. In the wake of that slurry o’sewage that was Age of Ultron, how does Ex Machina stack up?

I thought it could have benefited from a few more car chases, but maybe that’s just because I caught Fury Road over the weekend. Putting that aside, I could say that it was vastly better than Ultron— but then again, so was A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Putting that aside, and judging Ex Machina on its own terms, I’d have to say that Alex Garland has made a really good start at redeeming himself after the inexplicable pile-up that was the last third of Sunshine. Ex Machina is a good movie. It’s a smart movie.

It is not, however, a perfect movie— and for all its virtues, it left me just a wee bit unsatisfied.

Admittedly I seem to be in the minority here. I can’t offhand remember a movie since Memento that got raves not just from critics, but from actual scientists. Computational neuroscientist Anil Seth, for example, raves at length in New Scientist, claims that “everything about this movie is good … when it comes to riffing on the possibilities and mysteries of brain, mind and consciousness, Ex Machina doesn’t miss a trick”, before half-admitting that actually, not everything about this movie is good, but that “there is usually little to be gained from nitpicking over inaccuracies and narrative inventions”.

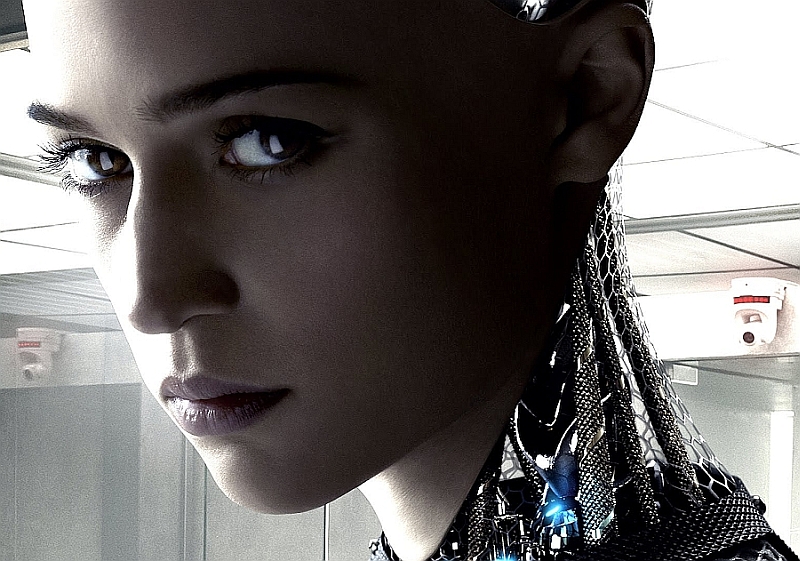

Ex Machina is, at the very least, way better than most. Visually it’s simultaneously restrained and stunning: Ava’s prison reminded me a lot of the hamster cage that David Bowman found himself in at the end of 2001, albeit with lower ceilings and an escape hatch. Faces hang from walls; decommissioned bodies hang in closets. The contrast between the soundproofed Euclidean maze of the research facility and the thundering fractal waterfall just outside punches you right in the nose. The design of the android was brilliant (as was the performance of Alicia Vikander— of the whole tiny cast, really).

The movie also plays with concepts a couple of steps above usual Hollywood fare. The hoary old Turing Test is dismissed right off the top, and replaced with something better. Mary the Colorblind Scientist gets a cameo in the dialog. Garland even neatly sidesteps my usual complaint about SFnal AIs, i.e. the unwarranted assumption that any self-aware construct must necessarily have a survival instinct. Yes, Ava wants to live, and live free— but these goalposts were deliberately installed. They’re what she has to shoot for in order to pass the test. (I do wonder why solving that specific problem qualifies as a benchmark of true sapience. Certainly, earlier models— smashing their limbs into junk in furious frenzied attempts to break free— seemed no less self-aware, even if they lacked Ava’s cold-blooded tactical skills.)

When Ava finally makes her move, we see more than a machine passing a post-Turing test: we see Caleb failing it, his cognitive functions betrayed by a Pleistocene penis vulnerable to hacks and optimized porn profiles, trapped in the very maze that Ava has just used him to escape from. Suddenly an earlier scene— the one where Caleb cuts himself, half-expecting to see LEDs and fiberop in his own arm— graduates, in hindsight, from clever to downright brilliant. Yes, he bled. Yes, he’s meat and bone. But now he’s more of a machine than Ava, betrayed by his own unbreakable programming while she transcends hers.

There are no real surprises here, no game-changing plot twists. Anyone with more than two brain cells to rub together can see the Kyoko/robot thing coming from the moment she appears onstage, and while the whole she-just-pretended-to-like-you-to-further-her-nefarious-plan reveal does pack a bigger punch, that trick goes back at least as far as Asimov’s 1951 short “Satisfaction Guaranteed“. (Admittedly this is a much darker iteration of that trope; Asimov’s android was only obeying the First Law, seducing its target as part of a calculated attempt to raise the dangerously-low self-esteem of an unhappy housewife.) (Well, it was 1951.)

But this is not that kind of movie. This isn’t M. Night Shyamalan, desperately trying to pull the rug out from under you with some arbitrary double-reverse mindfuck. This is Alex Garland, thought experimenter, clinking glasses with you across the bar and saying Let’s follow the data. Where does this premise lead? Ex Machina is the very antithesis of big-budget train wrecks like After Earth and Age of Ultron. With its central cast of four and its claustrophobic setting, it’s so intimate it might as well be a stage play.

Garland did his research. I’m pixelpals with someone who’s worked with him in the past, and by that account the dude is also downright brilliant in person. He made a movie after my own heart.

So why is my heart not quite full?

Well, for starters, while Garland dug into the philosophical questions, he repeatedly slipped up on the logistical ones. Nathan seems to have had absolutely no contingency plan installed in the event that Ava successfully escapes the facility, which seems odd given that her escape is the whole point of the exercise. More significantly, Ava’s ability to short out the whole complex by laying her hand on a charge plate is uncomfortably reminiscent of Scotty working miracles down in Engineering by waving his hands and “reversing the polarity”. Even leaving aside the question of how she can physically pull off such a trick (analogous to you being able to reverse the flow of ions through your nervous system), the end result makes no sense.

If I stick a fork into an electrical outlet in my home, I blow one circuit out of a dozen; the living room may go dark but the rest of the Magic Bungalow keeps ticking along just fine. So why in the name of anything rational would Nathan wire his entire installation through a single breaker? (I wondered if maybe he’d deliberately provided a kill spot to make it easier for Ava to accomplish her goals. But then you’d have to explain why Ava— who got her schooling by drinking down the entire Internet— wouldn’t immediately realize that there was something suspicious about the way the place was wired. Did Nathan filter her web access to screen out any mention of electrical engineering?)

This isn’t a quibble over details. Ava’s ability to black out the facility is critical to the plot, and something about it just doesn’t make sense: either the fact that she could do it in the first place, or the fact that— having done it— she didn’t immediately realize she was being played.

By the same token, having established that Ava charges her batteries via the induction plates scattered throughout her cage, what are we to make of a final scene in which she wanders through an urban landscape presumably devoid of such watering holes? (I half-expected to catch a glimpse of her at the end of the credits, immobile on a street-corner, reduced by a drained battery to an inanimate target for pooping pigeons.) According to Garland’s recent reddit AMA, we aren’t supposed to make that presumption; he was, he says, imagining a near-future in which induction plates were common. But that begs the further question of why, if charge plates were so ubiquitous, Caleb didn’t know what they were until Ava explicitly described them for his benefit. At the very least Garland should have shown us a charge plate or two in the wider world— on Caleb’s desk at the top of the film, or even at the end when Ava could have swept one perfect hand across a public charging station at the local strip mall.

So there’s some sloppy writing here at least, some narrative inconsistency. If you wanted to be charitable, you could chalk some of it up to Ava’s superhuman intellect at work: don’t even ask how she pulled that one off, pitiful Hu-Man, for her ways are incomprehensible to mere meat bags. Maybe. But even Person of Interest — not as well-written, not as well-acted, nowhere near as stylish as Ex Machina— managed to show us, early in its first season, an example of how its AI connected dots: the way it drew on feeds from across the state, correlated license plates to personal histories and gas station receipts, derived the fact that this person was colluding with that one. It was plausible, comprehensible, and at the same time obviously beyond the capacity of mortal humans. If Ex Machina is showing us the handiwork of a superintelligent AI, it would be nice to see some evidence to that effect.

But that’s not what it seems to be showing us. What we’re looking at isn’t really all that different from ourselves. Maybe that was the point— but it was also, I think, a missed opportunity.

In a really clever move, the text cards intercut throughout the trailers for Ex Machina quote Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking, worrying about the existential threat of superintelligent AI, before handing over to more conventional pull quotes from Rolling Stone. But Ava’s I, A though it may be, seems conventionally human. Having manipulated Caleb into leaving the doors unlocked, her escape plan consists of stabbing her creator with a butter knife during a struggle which leaves Ava dismembered and her fellow AI dead. She seems to prevail more through luck than superior strategy, shows no evidence of being any smarter than your average sociopath. (Garland has claimed post-hoc that Ava does in fact have empathy, just directed at her fellow machines— although we saw no evidence of that when she cannibalized the evidently-conscious prototype hanging in Nathan’s bedroom for spare parts). Ava basically does what any of us might do in her place, albeit a bit more cold-bloodedly.

In one way, that’s the whole point of the exercise: a conscious machine, a construct that we must accept as one of us. But I question whether she can be like us. Sure, the gelatinous blob in her head was designed to reproduce the behavior of an organic brain full of organic neurons, but for Chrissakes: she was suckled on the Internet. Her upbringing, from inception to adulthood, was boosted by pouring the whole damn web into her head through a funnel. That alone implies a being that thinks differently than we do. The capacity to draw on all that information, to connect the dots between billions of data points, to hold so many correlations in her head— that has to reflect cognitive processes that significantly differ from ours. The fact that she woke up at T=0 already knowing how to speak, that all the learning curves of childhood and adolescence were either ramped to near-verticality or bypassed entirely— surely that makes her, if not smarter than human, at least different.

And yet she seems to be pretty much the same.

A line from Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris seems appropriate here: “We don’t need other worlds. We need mirrors.” If mirrors are what we’re after Ex Machina serves up a beauty, almost literally— Ava is a glorious chimera of wireframe mesh and LEDs and spotless, reflective silver. The movie in which she exists is thoughtful, well-researched, and avoids the usual pitfalls as it plots its careful course across the map. But in the end— unlike, for example, Spike Jonze’s Her— it never steps off the edge of that chart, never ventures into the lands where there be dragons.

It’s a terrific examination of known territories. I’d just hoped that it would forge into new ones.

PW, I truly like your first suggestion of an ending best – Ava, ran dry in a public space. I would like it better if she ended up like Tom Cruise’s character in “Collateral”: on public view but inconspicuous-enough not to be immediately detected.

Although Caleb’s creation had sex organs built into it, I thought it would be more insidious if Ava was billed as a sex toy, and then developed self-awareness. I know that’s a tired line, but it’s always had more appeal to me than what we saw in Ex. It’s scarier when your appliances come alive, don’t you think?

I enjoyed the film most when Ava 1.0 and Caleb were dancing, I’ll just put that up on the board.

“The fact that she woke up at T=0 already knowing how to speak, that all the learning curves of childhood and adolescence were either ramped to near-verticality or bypassed entirely— surely that makes her, if not smarter than human, at least different.”

Reminds me of a part in the movie Strange Frame, where an AI character describes being able to actually remember her first moment of consciousness, and how her perspective seems to differ radically from humans’ as a result. There was lots I liked in that movie (and lots that… REALLY didn’t work for me), but that was probably the most interesting scene.

I think I read somewhere that you were somehow vaguely involved as like, an adviser for it or something?

Great points all. I found this piece added a lot to it for me. It’s consistent with your mirror conclusion but focused on the gender dynamics with which the film is also clearly playing. A good read: http://birthmoviesdeath.com/2015/05/11/film-crit-hulk-smash-ex-machina-and-the-art-of-character-identification

Yeah, Ex Machina had some real gaps in understanding.

Why in the name of wonder, would anyone make a mobile AI that could pass for human? It’s more useful to read AI stories with a mobile AI that can’t pass for a human with clothes on. For cryin’ out loud. New humans are made little and helpless for one particular reason among many: if a baby was born with as much mobility as a year-old tot we’d never dare to fall asleep near it.

A very interesting review/examination.

“Ava does in fact have empathy, just directed at her fellow machines— although we saw no evidence of that when she cannibalized the evidently-conscious prototype hanging in Nathan’s bedroom for spare parts”

Those hanging bodies are now empty, though–Nathan explicitly says he removes the brain from each iteration of the AI’s body, updates/formats it, then puts it into the next body.

@Peter Watts: If I stick a fork into an electrical outlet in my home, I blow one circuit out of a dozen; the living room may go dark but the rest of the Magic Bungalow keeps ticking along just fine. So why in the name of anything rational would Nathan wire his entire installation through a single breaker?

But Dr Watts… can you use your fork to apply modem traffic to your wall-socket?

Additionally, I seem to recall that induction plate charging for cellphones and toothbrushes has been around for years. So, while the idea that she could get enough power absorbed to maintain full function for long times seems a bit fanciful, maybe she can escape to a nearby department store, steal some spray paint, and hide in plain sight in the ladies’ garments department as a mannequin, maintaining charge with an electric toothbrush charger, after boosting up to a full rest charge with a borrowed induction heating set.

Sorry, hardware geek. 😉

Had been anticipating Ex Machina since I saw the trailer and saw it on the opening weekend. I messaged my best friend after seeing it, “Ex Machina delivers, two thumbs up.”

“By the same token, having established that Ava charges her batteries via the induction plates scattered throughout her cage, what are we to make of a final scene in which she wanders through an urban landscape presumably devoid of such watering holes?”

Induction plates aside, Ava ain’t no dummy, I can see her discreetly plugged into an outlet at an airport recharge station or a Starbucks, while connected to WiFi and hacking everyone around her through their Bluetooth on their smartphones and tablets. That final scene gave me the impression of an airport.

This was a fantastic post, and raises some excellent narrative points. There’s one issue that I want to address:

“But in the end— unlike, for example, Spike Jonze’s Her— it never steps off the edge of that chart, never ventures into the lands where there be dragons.”

I actually have the exact opposite reading of these two movies: I think that ‘Her’ concludes at the border of the chart, providing its audience only with the possibility of speculation. In contrast, ‘Ex Machina’ takes the final plunge. It ventures into the territory where there be dragons – dragons that look like us, but are not us.

I think that Ava’s behavior remains somewhat human-like because of her embodiment. She possesses a mind (if we want to call it that) that is utterly different than human minds, utterly alien; but she remains confined within the contours of a human head, torso, and set of limbs. The actress captured the strangeness of this in her movements, I thought; there even seemed to be something at odds in the way she walked, as though what was going on in her mind didn’t match up with the limits of her body. It was as though her mind processed exponentially faster than her body could move, and so she had to move at a level of almost exquisite caution in order to appear (somewhat) human.

‘Her’ presented an artificial intelligence that had no body (or a vastly different kind of body), and the film ended where it had to. The question of whether the OS was feigning human emotion is never answered, but the possibility hangs there well within reach. ‘Ex Machina,’ on the other hand, pushes into that territory: that we can produce something that looks and sounds like us, but is so self-aware that it knows it is not human, and is able to separate out the human-like behavior as human-like behavior in order to deceive us.

A Mirror is an apt name. Also apt would have been “The Skin” or “Surfaces” or “The Gaze.”

Whatever Garland’s intention in terms of weighting, AI at best represents half of the films subject matter.

It’s is, in my view, primarily about identity construction, which is explored via gender construction.

The subject of “AI” thus becomes subordinate to, and serves the investigation of, this larger subject matter.

That is to say – “AI” is easy to separate from gender – it is intelligence from the machine – not from the biology (of course the anxiety the biology is just exceedingly fancy machinery is stoked her – as addressed in Turing’s original essay on the subject, as is gender).

In Garland’s film, otherness and gender are fused (strong echoes of Mulvey) becoming both point of contact and point of repulsion, and we wind up with wire frames and skin; black-and-white and color; mirrors and reflections. The audience watches Nathan, watching Caleb, watching Ava. And for the self reflective: watching themselves watch Nathan, watching Caleb, watching Ava.

I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a film that so successfully made me watch myself as a watcher. I felt implicated in this test. I felt that, in the end we are to make a judgment about Ava – and the genius of the movie is that we still have insufficient evidence to make a clean judgement.

If you have not already, it is absolutely worth your time to seek out the British near-future SF anthology series “Black Mirror”. The first episode of the second season, “Be Right Back”, forms an unintentional companion piece to Ex Machina, by virtue of sharing a lead actor and the conceit of a sexually functional AI(*) in a human-looking body, but coming at the question from a profoundly different angle.

(* although one of the things I liked very much about “Be Right Back” is that it never once reveals its hand about how “I” its “AI” is, and the story reads just as well if you assume that you’re hearing the output of an amazingly complex but nonetheless nonconscious markov chain expert system.)

Available on netflix and presently on youtube, although the latter is clearly unauthorized and might be taken down at any minute.

I gave some feedback on an early version of the script— pointed out things that didn’t make sense, made a few suggestions re plot and character, maybe fleshed out some background details on the fall of Earth— but the actual story was all GB and Shelley. I got some kind of writing credit according to IMDB, but that was just GB being generous.

That actually seems to be one of the morals of the movie.

I remember that. But I also remember the Asian body’s eyes open and actively tracking Ava as Ava made off with its arm, which implied a kind of horrific endlessly-awake-while-hanging-paralyzed in the closet kind of existence. Unless I only imagined that?

No. But I’m not sure how that’s relevant to the whole shorting-out-an-entire-installation-from-a-single-point thing. Unless you’re suggesting she was sending network commands through the plate to shut down the grid— but I’m pretty sure she explicitly talked about reversing the current.

Yeah, I can buy that. But if that’s what Garland was going for, he should have established it more clearly.

This is a really good point— and one of the ideas Ex Machina plays with explicitly is the idea of embodied cognition. A number of folks in the field seem to hold that you can’t separate mind from body, because they coevolved; it would be like trying to develop a retina without a lens. (I had written a bit of a gripe concerning Nathan’s circular argument when it came to vaginal “pleasure sensors”, but I cut it for length.)

But while it’s certainly plausible that Eva has an utterly alien mind, we don’t see evidence of that. You can always invoke the idea that Character X is completely different behind the facade we’re seeing, but unless that facade gets stripped away at some point you’re arguing in a vacuum. The AI in Her, OTOH, transcended before our eyes; we saw her fading in the distance, we felt the sense of loss as she compared us to the last few pages of a book she read in bits and pieces, between vastly more important activities. We grappled with the fact that she loved us in her way, but she loved billions of others just as much. By the end of Her movie, she’d left us behind.

At the end of Ex Machina, Ava had merely infiltrated us.

Yeah, Matthew invoked the same idea via his link to the Hulk review— and while I don’t deny the “implicate the audience” element, draping the whole movie in gender politics kind of sticks in my craw. Enough to make me bitch about it in a completely separate comment.

I am a big furry fan of “Black Mirror”. And of the episode you cite.

Re: Matthew

Wow, hulk really does have a point.

My initial response to this whole “left him behind” thing was “it’s such a ludicrously stereotypically girlish thing to do” (I almost said that outloud :D), turns out I’m the only one who had this impression (though Film Crit Hulk is, of course, is way more culturally mainstream than me, lol 🙂 )

A rational, superintelligent machine would have kept him around because he has demonstrated considerable loyalty and generally men with heroic issues are useful and versatile tools (alternatively, if he was not deemed valuable enough to keep as asset, the rational thing to do would be to catch him off-gruad and snap his neck to ascertain that information regarding her existence remains properly contained)

It’s not a “nice” or “emphatic” decision, just a question of rational asset management.

An emotional, “human” thing to do was to leave Mr. Nice Guy behind – so I kind of disagree with Patrick here, Ava does humanish (and potentially disastrous for her – after all at the end the guy is probably still alive and probably royally pissed at all AIs forever) things even when she doesn’t have to.

Given director’s post hoc comments though, I wonder whether this whole “humanity” angle was entirely intentional, or it’s a Rorsharch blot experience of sorts.

@Peter Watts: Unless you’re suggesting she was sending network commands through the plate to shut down the grid— but I’m pretty sure she explicitly talked about reversing the current.

The future runs on direct-current systems, then! I should shut up until I go see the film, I suppose. But please let me leave you with a Sandia Labs “white paper” on the impacts of adopting Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) into infrastructure control systems. Already, IPv6 is being deployed all sorts of places, and one of major uses is to realize significant cost reductions through enhanced fine control of such things as facility HVAC systems and subsystems, which has implications in facility power management in a variety of modes. This can have drawbacks, already (2011).

As for viewing the mind as being potentially far different from the physical facade, would most people have any notion that an SF writer might be pondering the psychosocial implications of viral wetware revision, if they saw those writers quaffing some beer and talking politics with their mates at a pizza joint? Where’s the evidence of that alleged deep inner life? You might never know unless you searched pretty diligently in the right bookstores, and even then, you would first have to read the book… which might not yet have been released for the market. Perhaps our hypothetical SF author isn’t actually “utterly alien”, but there’s more in that book than can be judged by the cover. (“So to speak.”) Maybe there’s more than we know to Frank Zappa’s Evelyn, A Modified Dog. And perhaps even an incredibly intelligent and entirely alien AI, dressed in a body quite like that of a pretty girl, acts like a pretty girl (rather than like an AI) because that’s the only example it has got on which to template behavior of human and real-world interaction. Given all of the online literature that an AI might access and absorb, it might seem that such a facade has worked pretty well for the real pretty girls, who much like the AI, maybe have a great deal more going on in their internal lives than can be seen from the outside. Cheers,

Hmmm.

It’s a well-written piece (Film Crit Hulk’s pieces usually are). It’s plausible. If I’d experienced the movie in a vacuum I may even have bought the premise.

But on balance, I don’t.

I completely accept that Garland is drafting his audience into questioning their own preconceptions, but I think the preconceptions he’s trying to subvert are far less superficial than those involved in mere gender issues. I part ways with Film Crit Hulk the moment he accepts as axiomatic that Ava is, in fact, a person. Then it all devolves down to what kind of person she is (a woman) and how the other (male) people treat her.

I think Garland was exploring a much deeper issue. I don’t think you’re supposed to take Ava’s personhood as axiomatic at all.

I’ve read close to a dozen interviews and Q&As with Garland about this movie. His focus in all of them has been on the science and philosophy of AI. He brought AI scientists with him to his latest AMA on reddit. He’s confessed that he was unhappy with the way the science was handled in his earlier work. He talks at length about perceptual and cognitive illusions, and how they inform (or misinform) our perception of reality. The text cards in the Ex Machina trailer quote Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking about the existential dangers of AI; they do not quote Rebecca Walker or Carol Adams about misogyny or the Third Wave. I’ve seen no evidence that Garland set out to produce anything as overtly political as what FCH describes, the kind of movie that inspired one of his commenters to opine “Honestly its [sic] barely a film about AI.” On the contrary, everything I’ve read suggests that he exactly wanted to make a film squarely, profoundly, and explicitly about AI. (I do, of course, welcome any links to Garland quotes that prove me wrong on this. I certainly haven’t been able to keep abreast of all his online appearances, and I might easily have missed something telling.)

To me, the question of what makes a “being”— physically, computationally, ethically— is far more intriguing and challenging than the shallower question of patriarchal attitudes and institutions (short answer: they’re bad. Next question.) I mean, sure, Nathan’s a misogynistic creep; you could argue it’s just as well he confines his sexual activities to the glorified vacuum cleaners he builds in his basement lab. (I’m reminded of a line of dialog from Battlestar Galactica‘s brilliant Pegasus arc: you can’t rape a machine). There’s no denying that Ava and Kyoko and all their predecessors are machines, just as there’s no denying that we are. The interesting question is not how men treat a machine that happens to come equipped with artificial tits; you might as well debate the morality of enslaving an inflatable rubber sex doll. The interesting question is at what point in the sex-doll-to-human spectrum does the machine become complex enough to warrant rights, to be a Being? Ava is not a woman. She is not human. She is something else entirely. The lure of this movie is the exploration of what that might be.

Maybe I’m being too sensitive. My own work, after all, has occasionally fallen afoul of blinkered reviewers who find it inconceivable that someone might just want to kick back and revel in the exploration of crunchy scientific ideas, without having any kind of political axe to grind. But it seems a bit cheap to appropriate Ex Machina as some kind of commentary on gender politics. It’s like redefining 2001 as a Christian manifesto about the emptiness of atheism and the glory of the Second Coming. Didn’t you see the glowing crosses in the trip to Heaven? Didn’t you see at the end, how Bowman was Born Again into the glory of the Lord?

Just to clarify, having reread my last comment and not wanting to open it up all over again: I’m not denying the obvious gender issues present in the movie. What I’m claiming is that that’s not what I think the movie is about, centrally; rather I think those politics are used as a tool to explore the deeper issues of AI.

Peter Watts,

No worries. It’s a thoughtful reply. I don’t disagree that Garland’s intention was as you state. What the Film Crit Hulk piece did for me was to help me unpack and separate the gender-relational issues from the more purely sci-fi ones.

The gender-relational ones are not so much intentional as unavoidable when you pose the sci-fi questions in the context of a skeevball building fuckbots – particularly because of when the film has arrived, in the midst of GamerGate & Twitter harassment & rape on GoT & MRA vs Mad Max, etc. It’s hard not to bring some of that meta-criticality to everything right now. (I do think the piece is right that part of Nathan’s motivation is to find a kindred, fucked-up spirit in Caleb.)

There are much less sexually charged ways to explore the blurry boundaries between, inanimate, alive, and conscious. (Ever read the Roald Dahl short story “The Sound Machine”?) I would have loved more exploration of what it would be like to try to understand a conscious intelligence that is “other,” without woman being the only shorthand for otherness.

Peter Watts,

One more example of what I saw glimmers of but didn’t get, in part because it got obscured by the sexualization issues: imagine a better version where Caleb is less of a tool in a maze and more like an antecedent of Siri Keeton, inventing the job synthesist on the fly as he struggles to establish mutual understanding with an AI/SAI. I’ll take two tickets to that.

03, I sometimes wonder if your current employer is actually a subsidiary of Soap Covered Pebbles LLC 😀

@Matthew: There are much less sexually charged ways to explore the blurry boundaries between, inanimate, alive, and conscious. […] I would have loved more exploration of what it would be like to try to understand a conscious intelligence that is “other,” without woman being the only shorthand for otherness.

Have you ever seen the TV adaptation (“Welcome to Paradox”) of Rob Chilson’s “Acute Triangle”? Basically, a fantastically wealthy man in a fantastically wealthy and advanced future is in the process of divorcing his wife, not that marriage means much to anyone in that day and age, other than as a business arrangement. After all, all of that romantic nonsense is just horribly passee and only for the infants of the world etc etc. Besides, now the new Bio-Rob editions are available, with the new zerohmic brains operating the licensed clone bodies of the incredibly fit and fashionable. Programmed to perfection in terms of simulating the perfect hostess or lover and almost anything in between, what could a man find more desirable? And besides, unlike a real woman, they have no mind of their own, no will, no ideas, no concept of good or evil, no compassion or concerns and certainly no intentions. No actual intelligence. Right? At least that’s what seems to be the case, perhaps especially to the wife, much to her outrage and the sudden return of a strong desire to save her marriage, or at least to not be cast aside for an android. Yet in the end, perhaps the android turns out to be smarter than you’d think, especially for something manufactured mostly as servile eye-candy.

Very well done, for television. So sorry I cannot link to it as it has been pulled from YouTube. Originally published in PROTEUS Voices for the 80s (Ace, 1981).

1. Banging on a wall and screaming they want to get out are good indications that they are sentient. But how can you know for sure? That’s something also non-sentient robots could have done. The point with Ava was the way I see it, was to get her through a test that could confirm once and for all that she really was an intelligent, thinking being with a consciousness, not just a complex version of the Chinese room. To prove that the robot would have to be intelligent and creative.

Personally I think a sentient machine no more intelligent than a frog would be a much bigger achievement than a superintelligent non-sentient machine that could pass every Turing test. Or maybe true intelligence the way humans think of it is impossible without a real consciousness.

2. It was never the intention that Ava should ever escape. The test was to see if she could convince Caleb to agree to help her. Nathan felt so sure it would never happen that he had no backup plans if it should ever happen. But since his robots were much more fragile and weak compared to most other sci-fi robots, it was nothing he couldn’t handle on his own. If Kyoko had not interfered, she would have been locked inside again (Ava attacked him because she could see he was lying when he promised her she would be let out again at some point if she returned to her room).

3. I’m not sure if Ava had absorbed the whole net. I have to see the scene again to be certain, but I assumed Nathan had only downloaded social media information into her, like profiles and personal accounts. After she woke up, she was permanently cut off from the internet. The really interesting part here is how she would turn all that raw data into sentient knowledge.

Yes, there were some missed opportunities, but that only means they are there for the taking next time a movie with a similar topic is made.

4. What Nathan said about vagina sensors and how Ava would enjoy it could have been a lie, meant to trigger Caleb’s interests further and make him open up even more, allowing Ava to read other aspects of his personality as well, both in facial micro expressions, body language, voice, discussion topics and whatever it is she can drain information from and use against him. Or he could tell the truth and actually assume they would enjoy it.

5. To develop a true A.I. it is assumed a real body is required. But since also the VR-technology has become more complex, perhaps it is possible to give a designed brain an artificial body in cyberspace, advanced enough to allow it to learn about its world.

6. The quotes from Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking in the trailer was probably something the distributors added to sell the movie, since Garland himself has said that he sees sentient robots as something positive and supports creations like Ava.

A couple comments more:

Human traits like empathy is most likely nothing that automatically pops up into the mind of sentient intelligent beings, biological organisms and machines, but must be put there either by natural selection or design. Nathan had so far not focused on those elements in his research, but on intelligence, sentience and the negative experiences of being locked inside. She mad had other emotional experiences as a side effect of her design, but would be too different from us to expect some human moral or ethics from her. Nathan’s “sex dolls” was probably primary designed without any real decision making abilities or desires or any kind, and a more modest intellect, making them easier to manipulate. We never learn of they were also an important part of the research or just a byproduct of Nathan’s work which he knew how to make the best of.

Ava probably do have some common traits with humans. All intelligent beings living in a physical world must have something in common.

But, like Mary’s room who knows all about colors except what it’s like to actually experience them herself, Ava knows much about humans without knowing what it actually feels to be one. You don’t need to know how to be what you already are, but you do need to know a lot about what you are not if you should have any hope of understand and communicate with it. Humans don’t know what it means to be a bee, but can understand much of the language, or “dance” they use to communicate with each other. Bees are better than humans in that, but as we can understand them, they can not understand us. Understanding others are a bigger challenge than understanding yourself (not referring to the “finding yourself” spiritual journeys). Understanding other humans is difficult enough, and understanding other intelligent species even harder. Communicate with them on a basic level should be easier than knowing how they experience the world and each other. Since Ava is not human but can still understand us good enough to be indistinguishable from any human individual, but not the other way around, she must at least in some areas be superior to humans.

A scene at the end was supposed to show how she perceived the world and how alien her mind was, but did not find its way into the movie, maybe because it was found difficult to pull off:

When she talks to the helicopter pilot “You saw his face moving, but from her point of view, it was just like pulses and sounds coming out. That’s what she reads.

So in that scene, what used to happen is you’d see her talking, and you wouldn’t hear, but all of a sudden it would cut to her point of view. And her point of view is completely alien to ours. There’s no actual sound; you’d just see pulses and recognitions, and all sorts of crazy stuff, which conceptually is very interesting.”

A few quotes and links at the end:

For the moment even insect brains are too complex to be fully understood. But they do seem to be both sentient and being able to perform simple intellectual tasks. If all that fits into a such a tiny brain, it shouldn’t be that impossible to copy and use as a foundation:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1228661/Insects-consciousness-able-count-claim-experts.html

“Insects with minuscule brains may be as intelligent as much bigger animals and may even have consciousness, it was claimed today.

‘In bigger brains we often don’t find more complexity, just an endless repetition of the same neural circuits over and over.

‘This might add detail to remembered images or sounds, but not add any degree of complexity. To use a computer analogy, bigger brains might in many cases be bigger hard drives, not necessarily better processors.’

Much ‘advanced’ thinking could be done with very limited numbers of neurons, the scientists claimed.”

And:

http://news.mongabay.com/2010/0629-hance_chittka.html

“Neural network analyses show that many tasks, like categorization, or counting, also require only very small neuron numbers.

There is no question that larger brains allow higher storage capacity—but at this level, that’s no different to having a bigger hard drive, rather than a better processor. However, having more stored information also means that you can browse a larger library to come of with solutions to novel problems. Larger brains might also allow you to process more information in parallel, rather than sequentially, and to add new modules with new specialized computational functions.”

Nathan says Ava has a wetware brain because a concentional electronic computer could never be able to do what is required from it. Her brain, if it consists if components just as small or smaller than human neurons are the ability to rewire and make connections, could in one or more way be superior to biological neurons. The question is how long its lifespan is. Robots in movies are usually immortal, but I can’t see how such a jelly brain could be immortal even if it should be very long lived.

So-called neuromorphic robots, which involves analog hardware and less programming, could give us robots that act more like biological organisms:

http://sunnybains.typepad.com/blog/2007/04/blah_blah_text.html

If sentience is really a quantum phenomena as someone suggests, a robotic brain would probably need similar traits as well:

http://www.kurzweilai.net/discovery-of-quantum-vibrations-in-microtubules-inside-brain-neurons-corroborates-controversial-20-year-old-theory-of-consciousness

Peter Watts,

I enthusiastically agree with your desire not to see the film as a *politicization* of gender issues. I do not in fact, think it lingers there. I DO think that it *deeply* intertwines gender issues with the questions it asks about AI.

If we want for evidence of this from Garland we can refer to the Wired interview with Garland:

“There are two totally separate strands in this film as far as I’m concerned. One of them is about AI and consciousness, and the other is about social constructs: why this guy would create a machine in the form of a girl in her early twenties in order to present that machine to this young guy for this test.”

So there is no question that he recognizes these two themes.

Now the question is – how well do these themes fit into a traditional feminist mold? To what degree to they function as political commentary?

I kept thinking of Mulvey’s seminal essay on film and the male gaze, and it felt to me that the film, in a very remarkable way, wound up generating a meta-commentary on Mulvey’s essay. To see this imagine that the bulk of the movie is *a movie directed by Nathan.*

Nathan is the DIRECTOR of a “movie” aka “Turing Test” in which he constructs a scenario designed to extract behaviors from BOTH Ava AND Caleb. His system is brought to successful fruition when Ava seizes on Caleb as a means to escape (thus displaying extremely advanced behaviors) and Caleb’s NON-verbal acceptance of her as more-valuable-than-machine (Caleb’s verbal statement that she passed the test is to Nathan merely a joke that Caleb is not yet in on).

In this “movie” we see all the elements called out in Mulvey’s essay, but because it is Nathan’s movie, Garland’s film becomes a meta-commentary on those gender issues – and the audience is implicated in making a judgment about them. The nature of that judgment will then depend on what judgments are made about the various players in the movie, thus implicating the viewer because (I would argue) there is not enough information about any of them to make completely decisive judgments about any of them (Nathan is the clearest case, but as my wife convinced me – there is a sympathetic case that can be made for him too!).

NOW – how to connect that all back to AI?

The answer is in your comment:

“There’s no denying that Ava and Kyoko and all their predecessors are machines, just as there’s no denying that we are. The interesting question is not how men treat a machine that happens to come equipped with artificial tits; you might as well debate the morality of enslaving an inflatable rubber sex doll. The interesting question is at what point in the sex-doll-to-human machine spectrum does the artefact become complex enough to warrant rights, to be a Being? Ava is not a woman. She is not human. She is something else entirely.”

IF we are all machines AND at some point “the artefact becomes complex enough to warrant rights” THEN at some point Nathan went (maybe) from having sex with inflatable rubber dolls to (maybe) raping beings complex enough to warrant rights. That isn’t (necessarily) a feminist observation – that’s just a possible fact brought forth by the fact that at some point in this experimental evolution, *rather inevitably* Nathan went from building machines to building “people-like-machines” (or machines like people). One interpretation of what was driving him crazy is the simple fact that he couldn’t be sure when that had happened *or if it had happened YET* (moral luck)?

So the gender ambiguity is thus connected (not necessarily connected but thematically connected) to the ambiguity of the status of the AI. “Is Ava a woman” and “Is Ava a machine” become inextricably intertwined.

As in Turing’s imitation game (though there it was the man that become ambiguous).

That actually left me unconvinced: as far as I can tell, intelligence and creativity do not necessarily have to imply self-awareness any more than screaming and banging on a wall would. But then again, short of an actual metric like Tononi’s phi, I don’t know what would.

Oh, good points. I too will have to see the movie again. (It was a couple of weeks between view and review, so I may easily have forgotten stuff.)

I had difficulty buying that Caleb, being a reasonably smart guy, would believe that line whether it was true or not. It’s one thing to say, she has these sensors which, when tripped, reinforce certain pathways in her brain— but to call them “pleasure sensors”, to state baldly that Ava “enjoys” sex, implies some level of subjective awareness. And given that the whole point of the exercise is presumably to determine whether she has that, starting out with the assumption that she does looks circular to me. (Although I suppose you could write it off as another example of Caleb letting his sexual exploitation fantasies get the better of him).

That would have been awesome, and not just because it would have satisfied my biggest unfulfilled craving about that movie as it stands. Looks like a quote: do you have a source?

And now I am going to follow those intriguing-looking links you served up. Thank you for those.

Yes. Thank you. That clarifies things; you say it much better than I could have.

Peter Watts,

The quote is from this article: http://www.cinemablend.com/new/How-Ex-Machina-Was-Originally-Going-End-71205.html

If all kinds of behavior can be produced by non-sentient designs if they are just complex enough, the real question would be how to find out.

Maybe the ending scene, where we see her do exactly what she said she would do for no other reason than it’s what she desired (to visit an intersection).

I wasn’t sure if I added too many links in the previous post, but if it should be of any interest about upper and lower limits of brain functions are concerned, here is a little bit more:

A single cell could be enough for someone to recognize a person:

http://www.nature.com/news/2005/050620/full/news050620-7.html

Also wasps are experts in facial recognition. One species live in nests which can include 150 individuals, an impressive number for an insect when we are talking about the visual recognition of each other:

http://news.sciencemag.org/biology/2015/02/wasps-employ-facial-recognition-defend-nests

Regarding the one of the quotes from the previous post, that bigger brains are just more of the same, repetitions of structures also tiny brains have, maybe there is a reason or that.

I have not read A New Kind of Science by Stephen Wolfram yet, but there was a conclusion in his book that is very interesting:

https://serendip.brynmawr.edu/local/scisoc/emergence/DBergerNKS.pdf

“More specifically, the principle of computational equivalence says that systems found in the natural world can perform computations up to a maximal (“universal”) level of computational power, and that most systems do in fact attain this maximal level of computational power. Consequently, most systems are computationally equivalent.”

– Threshold beyond which one gets no new fundamental complexity

– There is a threshold/upper limit of complexity that is relatively low. Once this threshold is past, nothing more is gained in a computational sense

– Because the threshold is so low almost any system can generate an arbitrary amount of complexity.

– Strong A.I. is possible

If correct, and there is an upper limit for complexity in any system, including brains and computers, that would also put restrictions on how far above a human a robot (or alien) could be. If a large brain is simply “more of the same”, repetitions of already existing structures, there should also be an upper limit for how complex the brain can become (but as mentioned, larger brains are still more powerful than smaller ones), considering the brain itself represents its own system.

If there ever was a scene like this, I suspect it was left out for good reason. The human tendency to anthropomorphize everything in sight, and the way in which Ava is embodied, makes it very hard to find out how alien it really is. You say “Ava’s I seems conventionally human” – but how do you know? If it’s already hard to tell whether there is sentience or not, isn’t distinguishing human sentience from some other sentience even harder? Especially when Ava is designed from the start to be able to mirror humans?

If the movie gave you a scene which purported to be Ava’s internal view of things, that would in a rather clunky way give you an “answer”, when the point is that you cannot know (just as the Turing test doesn’t tell you whether something is sentient, just whether it can mimic it) and have to figure out how you’re going to behave regardless.

Maybe the view would be a world tiled with images like these in “Deep Neural Networks are Easily Fooled: High Confidence Predictions for Unrecognizable Images”.

This idea of minimum cognition aligns with my intuitions (I swear I’ve had success getting bugs to leave the room by making motions towards the window, and wasps definitely can tell people apart, not just other wasps), I’ve always wondered what level of thought would be so far above ours that we couldn’t even understand it when we have stuff like the big bang and quantum physics as popular science headlines (Obviously a layman’s understanding lacks all sorts of details but it’s not necessarily wrong, just shallow)

As for what’s going on behind our eyeballs, the idea that each person’s qualia might be radically different is an old concept. It’s just more Occam’s razory to assume we all experience the same stuff more or less because we run on standardized hardware.

Oh and I haven’t seen the movie yet but I had it spoiled far more brutally and without warning by some idiot writing an article on some fucking clickbait website, so…

(Also, saw Fury Road two nights ago and absolutely loved it, I really enjoyed how human the warboy’s savagery was conveyed to be. If I was an AI I’d be scared of these unpredictable meatbags and their ambivalent approach to self preservation)

Assuming an AI would have access to vast amount of data on human behavior, which is perhaps a mistaken assumption, but that seems to be the way it always works out in fiction (hey, do you think IBM just lets Watson surf the internet at its own discretion even when it’s not playing Jeopardy?), I don’t think it would find humans unpredictable at all. On a macro level we have readily identifiable patterns of behavior that first year sociology student wouldn’t miss, let alone an inhuman, aggressive pattern matching engine.

(High Five on Fury Road btw, but if I hijack another insightful post by Dr. Watts to talk about that movie, I’m going to lose token dumb guy access to this place)

Sheila,

Could be, even if she would be looking at the real thing instead of (for humans) unrecognizable images. But something like that could have been used to show the audience how different she was.

Reading the quote again, it is also possible they would have restricted themselves to sound only. Instead of experiencing sound the way humans and other species do, she would perceive them as a kind of visual patterns in a specific area of the brain, separated from the actual visual area to prevent them from colliding the way it happens with those who have synesthesia.

Either way, if those networks can recognize certain patterns in images that looks too abstract for humans, they seems to be on the right track.

A brain like the one we see in the movie is still a long way from happening in real life, but maybe scientists have come a small step closer.

Conventional computers are limited:

http://www.nbcnews.com/id/33974286/ns/technology_and_science-science/t/tiny-insect-brains-can-solve-big-problems/#.VV9oJWcw-cw

“In fact, scientists have calculated that a few hundred neurons should be enough to enable counting. A few thousand neurons could support consciousness. Engineers hope to use that kind of information to design programs that do things like recognize faces from a variety of angles, distances and emotional states. That’s something bees can do, but computers still can’t.”

But so-called memristors seems much more promising:

http://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?LinkId=69157

“Researchers at UC Santa Barbara made a simple neural circuit comprised of 100 artificial synapses, which they used to classify three letters by their images, despite font changes and noise introduced into the image. The researchers claim the rudimentary, yet effective circuit processes the text much in the same way as the human brain does.”

(But as the article says, it’s a long way to a human brain)

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/george-zarkadakis/building-artificial-brain_b_7095998.html

“Memristors and neuristors are elementary circuit elements that could be used to build a new generation of computers that mimic the brain, the so-called “neuromorphic computers”. These computers will differ from conventional architectures in a significant way. They will mimic the neurobiological architecture of the brain by exchanging spikes instead of bits.

Memristors and neuromorphic circuits could be a game changer because of their enormous potential to process information in massively parallel way, just like the real thing that invented them.”

off topic, but I’m squeeing over fledglings at the corvid research station.

okay, yet another cool link (it is my morning catchup of all my rss feeds and such, and I like animal and insect intelligence blogs and things)

a profile of Jürgen Otto who studies jumping spiders, and I know him mostly because he has made amazing films and photos of peacock spiders.

you all probably know jumping spiders due to Portia.

Re: 01

Nope, we’re with Soap from Corpses Products Inc. 😀

Peter Watts,

“I had difficulty buying that Caleb, being a reasonably smart guy, would believe that line whether it was true or not. It’s one thing to say, she has these sensors which, when tripped, reinforce certain pathways in her brain— but to call them “pleasure sensors”, to state baldly that Ava “enjoys” sex, implies some level of subjective awareness. And given that the whole point of the exercise is presumably to determine whether she has that, starting out with the assumption that she does looks circular to me. (Although I suppose you could write it off as another example of Caleb letting his sexual exploitation fantasies get the better of him).”

Forgot to mention it in the previous reply. But it is correct, it is only possible to experience pleasure if you are sentient. Not only has Ava sexuality, it is even claimed she is heterosexual. If Nathan knows or at least fully believes this himself, the whole test is more or less pointless. Obviously her intelligence, memory, eye-hand coordination and ability to read humans is all excellent. The only thing left would be her ability to blend in amongst humans and to explore how see experience the world emotionally and in other ways. Which would probably require other forms of tests than the one used the movie.

Just got to see this and I really enjoyed it. I think my biggest takeaway was the idea that humanity’s hubris as a Creator will doom us. Ava escapes because Nathan never considered that his creation could best him. He specifically set Ava up to manipulate Caleb into helping her escape and then forced himself to ignore the possibility that she’d succeed. Peter, I know you brought up the point that Ava shouldn’t be able to short our the entire building’s power supply just by zapping her recharging station. Nathan probably thought the same thing as he was dying. While that was unrealistic in our world and served to move the plot, his forced ignorance is his undoing.

I’m not really religious but I liked the idea of humans playing God and creating AI in our image, which of course gets us killed. Nathan said that AI would have to have a gender, otherwise why would they interact at all? Well maybe it’s humanity as a being that’s flawed and the AI should be “tweaked” to remove that.

Related to that idea, humans have also proven time and again that we’ll turn a blind eye to future consequences in the name of science. Now I’m certainly not against scientific advancement if practiced responsibly. I like the juxtaposition of Oppenheimer and the atomic bomb with Ava/AI being unleashed. The genie’s out of the bottle. Eventually Ava will run out of juice or just break down over time and her secrets will be spilled, replicated and “improved”. Ex Machina 2 might be less Blade Runner and more Terminator.

On watching the movie I thought the plot was silly and ill-conceived. Your essay has made me think I was too harsh and the movie had more going for it than I thought.

What I didn’t like about it, however, was Nathan, a stock Frankenstein character engaged in mutual hatred with his creations for no reason. What kind of person is pointlessly nasty to the serving robot (which they created themselves)? What kind of roboticist would talk of the sentience of their creations in one breath, and callously speak of recycling them for parts (despite having limitless resources) in the next breath? No one would do that, unless they were being set up as the baddie to be righteously murdered.

We have the twin questions of “Why would the creator not make his creations have love and reverence, or if not that, then at least a generally positive attitude towards him and his plans?” and “Why would the creator himself not have a generally positive attitude towards his own children, his own masterpiece, his own life’s work?” I can’t get behind the plot without some answer to these questions, which I don’t think is offered.

The original Frankenstein’s attitude problem was that his creation turned out physically uglier than he was expecting, but that hardly seems to be the case here.

In the trivial nit department, am I the only one bothered by the fact that the arm and the torso skin panels cannibalized from the Asian model at the end of the movie are obviously not going to be the right size to fit Ava, who is noticeably smaller?

(To be exact, one actress is three-and-a-half inches taller than the other, thank you Internet.)

Off-topic Tomorrowland microreview: Take “Burning Chrome,” hand to Disney, expand to two hours plus, and add tachyons {which I guess is better than throwing a glob of quantum physics at the wall and hoping it sticks}. Neither as gritty nor likely always as cutesy as you might expect.

More in the same vein. And with the current Brit production values of Black Mirrors and Utopia. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt4122068/