Dr. Fox and the Borg Collective

Take someone’s EEG as they squint really hard and think Hello. Email that brainwave off to a machine that’s been programmed to respond to it by tickling someone else’s brain with a flicker of blue light. Call the papers. Tell them you’ve invented telepathy.

Or: teach one rat to press a lever when she feels a certain itch. Outfit another with a sensor that pings when the visual cortex sparks a certain way. Wire them together so the sensor in one provokes the itch in the other: one rat sees the stimulus and the other presses the lever. Let Science Daily tell everyone that you’ve built the Borg Collective.

There’s been a lot of loose talk lately about hive minds. Most of it doesn’t live up to the hype. I got so irked by all that hyperbole— usually accompanied by a still from “The Matrix”, or a picture of Spock in the throes of a mind meld— that I spent a good chunk of my recent Aeon piece bitching about it. Most of these “breakthroughs”, I grumbled, couldn’t be properly described as hive consciousness or even garden-variety telepathy. I described it as the difference between experiencing an orgasm and watching a signal light on a distant hill spell out oh-god-oh-god-yes in Morse Code.

I had to allow, though, that it might be only a matter of time before you could scrape the hype off one of those stories and find some actual substance beneath. In fact, the bulk of my Aeon essay dealt with the implications of the day when all those headlines came true for real.

I think we might have just hit a milestone.

*

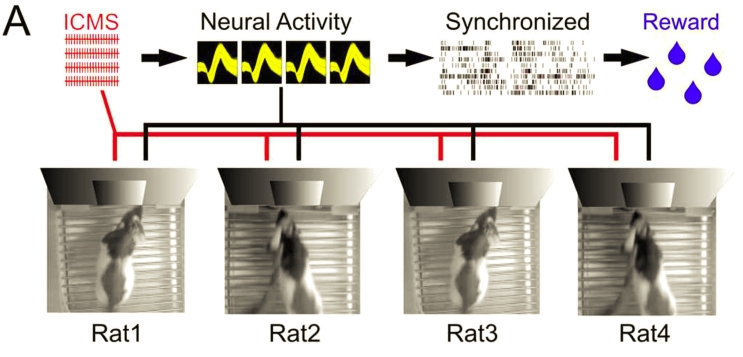

Here’s something else to try. Teach a bunch of thirsty rats to distinguish between two different sounds; motivate them with sips of water, which they don’t get unless they push the round lever when they hear “Sound 0” and the square one when they hear “Sound 1”.

Once they’ve learned to tell those sounds apart, turn them into living logic gates. Put ’em in a daisy-chain, for example, and make them play “Broken Telephone”: each rat has to figure out whether the input is 0 or 1 and pass that answer on to the next in line. Or stick ’em in parallel, give them each a sound to parse, let the next layer of rats figure out a mean response. Simple operant conditioning, right? The kind of stuff that was old before most of us were born.

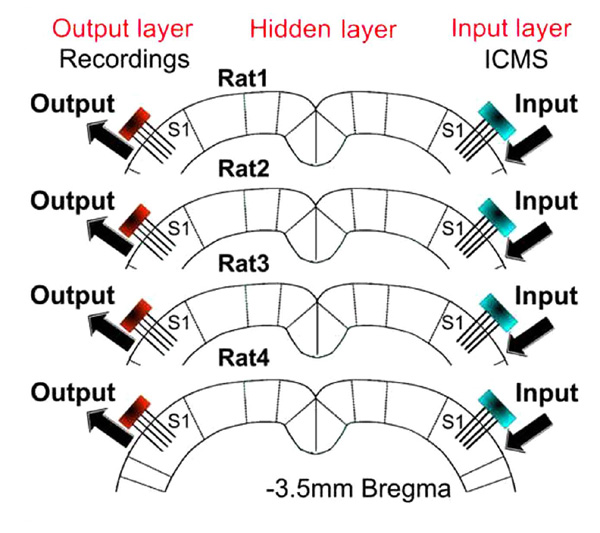

Now move the stimulus inside. Plant it directly into the somatosensory cortex via a microelectrode array (ICMS, for “IntraCortical MicroStimulation”). And instead of making the rats press levers, internalize that too: another array on the opposite side of the cortex, to transmit whatever neural activity it reads there.

Call it “brainet”. Pais-Vieira et al do.

The paper is “Building an organic computing device with multiple interconnected brains“, from the same folks who brought you Overhyped Rat Mind Meld and Monkey Videogame Hive. In addition to glowing reviews from the usual suspects, it has won over skeptics who’ve decried the hype associated with this sort of research in the past. It’s a tale of four rat brains wired together, doing stuff, and doing it better than singleton brains faced with the same tasks. (“Split-brain patients outperform normal folks on visual-search and pattern-recognition tasks,” I reminded you all back at Aeon; “two minds are better than one, even when they’re in the same head”). And the payoff is spelled out right there in the text: “A new type of computing device: an organic computer… could potentially exceed the performance of individual brains, due to a distributed and parallel computing architecture”.

Bicameral Order, anyone? Moksha Mind? How could I not love such a paper?

And yet I don’t. I like it well enough. It’s a solid contribution, a real advance, not nearly so guilty of perjury as some.

And yet I’m not sure I entirely trust it.

I can’t shake the sense it’s running some kind of con.

*

There’s much to praise. We’re talking about an actual network, multiple brains in real two-way communication, however rudimentary. That alone makes it a bigger deal than those candy-ass one-direction set-ups that usually get the kids in such a lather.

In fact, I’m still kind of surprised that the damn thing even works. You wouldn’t think that pin-cushioning a live brain with a grid of needles would accomplish much. How precisely could such a crude interface ever interact with all those billions of synapses, configured just so to work the way they do? We haven’t even figured out how brains balance their books in one skull; how much greater the insight, how many more years of research before we learn how to meld multiple minds, a state for which there’s no precedent in the history of life itself?

But it turns out to be way easier than it looks. Hook a blind rat up to a geomagnetic sensor with a simple pair of electrodes, and he’ll be able to navigate a maze— using ambient magnetic fields— as well as any sighted sibling. Splice the code for the right kind of opsin into a mouse genome and the little rodent will be able to perceive colors she never knew before. These are abilities unprecedented in the history of the clade— and yet somehow, brains figure out the user manuals on the fly. Borg Collectives may be simpler than we ever imagined: just plug one end of the wire into Brain A, the other into Brain B, and trust a hundred billion neurons to figure out the protocols on their own.

Which makes it a bit of a letdown, perhaps, when every experiment Pais-Vieira et al describe comes down, in the end, to the same simple choice between 0 and 1. Take the very climax of their paper, a combination of “discrete tactile stimulus classification, BtB interface, and tactile memory storage” bent to the real-world goal of weather prediction. Don’t get too excited— it was, they admit up front, a very simple exercise. No cloud cover, no POP, just an educated guess at whether the chance of rain is going up or down at any given time.

The front-end work was done by two pairs of rats wired into “dyads”; one dyad was told whether temperature was increasing (0) or decreasing (1), while the other was told the same about barometric pressure. If all went well, each simply spat out the same value that had been fed into it; they were then reintegrated into the full-scale 4-node brainet, which combined those previous outputs to decide whether the chance of precip was rising or falling. It was exactly the same kind of calculation, using exactly the same input, that showed up in other tasks from the same paper; the main difference was that this time around, the signals were labeled “temperature rising” or “temperature falling” instead of 0 and 1. No matter. It all still came down to another encore performance of Brainet’s big hit single, “Torn Between Two Signals”, although admittedly they played both acoustic and electric versions in the same set.

I’m aware of the obvious paradox in my attitude, by the way. On the one hand I can’t believe that such simple technology could work at all when interfaced with living brains; on the other hand I’m disappointed that it doesn’t do more.

I wonder how brainet would resolve those signals.

*

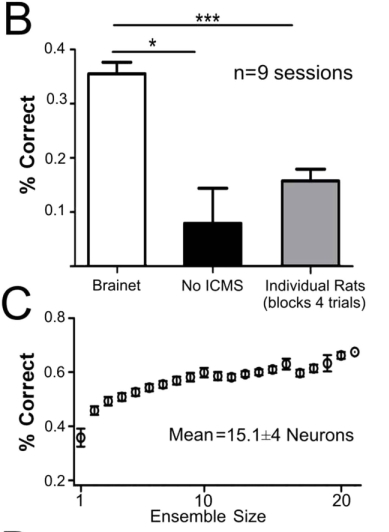

Of course, Pais-Vieira et al did more than paint weather icons on old variables. They ran brainet through other paces— that “broken telephone” variant I mentioned, for example, in which each node in turn had to pass on the signal it had received until that signal ended up back at the first rat in the chain— who (if the run was successful) identified the serially-massaged data as the same one it had started out with. In practice, this worked 35% of the time, a significantly higher success rate than the 6.25%— four iterations, 50:50 odds at each step— you’d expect from random chance. (Of course, the odds of simply getting the correct final answer were 50:50 regardless of how long the chain was; there were only two states to choose from. Pais-Vieira et al must have tallied up correct answers at each intermediate step when deriving their stats, because it would be really dumb not to; but I had to take a couple of passes at those paragraphs, because at least one sentence—

“the memory of a tactile stimulus could only be recovered if the individual BtB communication links worked correctly in all four consecutive trials.”

— was simply wrong. Whatever the merits of this paper, let’s just say that “clarity” doesn’t make the top ten.)

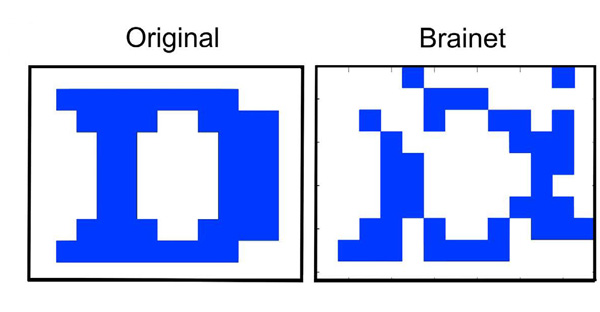

The researchers also used brainet to transmit simple images— again, with significant-albeit-non-mind-blowing results— and, convincingly showed that general performance improved with a greater number of brains in the net. On the one hand I wonder if this differs in any important way from simply polling a group of people with a true-false question and going with the majority response; wouldn’t that also tend towards greater accuracy with larger groups, simply because you’re drawing on a greater pool of experience? Is every Gallup focus group a hive mind?

On the other hand, maybe the answer is: yes, in a way. Conventional neurological wisdom describes even a single brain as a parliament of interacting modules. Maybe group surveys is exactly the way hive minds work.

*

So you cut them some slack. You look past the problematic statements because you can figure out what they were trying to say even if they didn’t say it very well. But the deeper you go, the harder it gets. We’re told, for example, that Rat 1 has successfully identified the signal she got from Rat 4— but how do we know that? Rat 4, after all, was only repeating a signal that originated with Rat 1 in the first place (albeit one relayed through two other rats). When R1’s brain says “0”, is it parsing the new input or remembering the old?

Sometimes the input array is used as a simple starting gun, a kick in the sulcus to tell the rats Ready, set, Go: sync up! Apparently the rat brains all light up the same way when that happens, which Pais-Vieira et al interpret as synchronization of neural states via Brain-to-Brain interface. Maybe they’re right. Then again, maybe rat brains just happen to light up that way when spiked with an electric charge. Maybe they were no more “interfaced” than four flowers, kilometers apart, who simultaneously turn their faces toward the same sun.

Ah, but synchronization improved over time, we’re told. Yes, and the rats could see each other through the plexiglass, could watch their fellows indulge in the “whisking and licking” behaviors that resulted from the stimulus. (I’m assuming here that “whisking” behavior has to do with whiskers and not the making of omelets, which would be a truly impressive demonstration of hive-mind capabilities.) Perhaps the interface, such as it was, was not through the brainet at all— but through the eyes.

I’m willing to forgive a lot of this stuff, partly because further experimentation resolves some of the ambiguity. (In one case, for example, the rats were rewarded only if their neural activity desynchronised, which is not something they’d be able to do without some sense of the thing they were supposed to be diverging from.) Still, the writing— and by extension, the logic behind it— seems a lot fuzzier than it should be. The authors apparently recognize this when they frankly admit

“One could argue that the Brainet operations demonstrated here could result from local responses of S1 neurons to ICMS.”

They then list six reasons to believe otherwise, only one of which cuts much ice with me (untrained rats didn’t outperform random chance when decoding input). The others— that performance improved during training, that anesthetized or inattentive animals didn’t outperform chance, that performance degraded with reduced trial time or a lack of reward— suggest, to me, only that performance was conscious and deliberate, not that it was “nonlocal”.

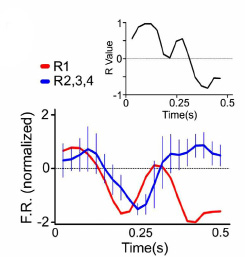

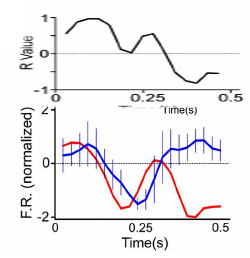

Perhaps I’m just not properly grasping the nuances of the work— but at least some of that blame has to be laid on the way the paper itself is written. It’s not that the writing is bad, necessarily; it’s actually worse than that. The writing is confusing— and sometimes it seems deliberately so. Take, for example, the following figure:

Four rats, their brains wired together. The red line shows the neural activity of one of those rats; the blue shows mean neural activity of the other three in the network, pooled. Straightforward, right? A figure designed to illustrate how closely the mind of one node syncs up with the rest of the hive.

Of course, a couple of lines weaving around a graph aren’t what you’d call a rigorous metric: at the very least you want a statistical measure of correlation between Hive and Individual, a hard number to hang your analysis on. That’s what R is, that little sub-graph inset upper right: a quantitative measure of how precisely synced those two lines are at any point on the time series.

So why is the upper graph barely more than half the width of the lower one?

The whole point of the figure is to illustrate the strength of the correlation at any given time. Why wouldn’t you present everything at a consistent scale, plot R along the same ruler as FR so that anyone who wants to know how tight the correlation is at time T can just see it? Why build a figure that obscures its own content until the reader surrenders, is forced to grab a ruler, and back-converts by hand?

What are you guys trying to cover?

*

Some of you have probably heard of the Dr. Fox Hypothesis. It postulates that “An unintelligible communication from a legitimate source in the recipient’s area of expertise will increase the recipient’s rating of the author’s competence.” More clearly, Bullshit Baffles Brains.

But note the qualification: “in the recipient’s area of expertise”. We’re not talking about some Ph.D. bullshitting an antivaxxer; we’re talking about an audience of experts being snowed by a guy speaking gibberish in their own field of expertise.

In light of this hypothesis, it shouldn’t surprise you that controlled experiments have shown that wordy, opaque sentences rank more highly in people’s minds than simple, clear ones which convey the same information. Correlational studies report that the more prestigious a scientific journal tends to be, the worse the quality of the writing you’ll find therein. (I read one fist-hand account of someone who submitted his first-draft manuscript— which even he described as “turgid and opaque”— to the same journal that had rejected the much-clearer 6th draft of the same paper. It was accepted with minor revisions.)

Pas-Vieira et al appears in Nature’s “Scientific Reports”. You don’t get much more prestigious than that.

So I come away from this paper with mixed feelings. I like what they’ve done— at least, I like what I think they’ve done. From what I can tell the data seem sound, even behind all the handwaving and obfuscation. And yet, this is a paper that acts as though it’s got something to hide, that draws your attention over here so you won’t notice what’s happening over there. It has issues, but none are fatal so far as I can tell. So why the smoke and mirrors? It’s like being told a wonderful secret by a used-car salesman.

These guys really had something to say.

Why didn’t they just fucking say it?

(You better appreciate this post, by the way. Even if it is dry as hell. It took me 19 hours to research and write the damn thing.

(I ought to put up a paywall.)

I do appreciate your effort and this damn thing. Saved to Evernote so I can read it a few more times.

Put up a patreon, let (other) people pay you to keep writing free blog posts. I need the charity. Paywalls reduce readership, you then have to go and advertise, gah.

As for the paper, you say it yourself, the system rewards obscurantism, so people learn to write that way. Occam’s razor says we don’t need to look any further…

People on online communities like reddit or 4chan already refer to themselves as a hive mind, jokingly, sort of. If they are hive minds, they’re not very smart, their main talents seem to be holding grudges.

Fascinating.

I kept thinking this is the Matrix. Rats/Mankind turned into a hive mind to satisfy the needs of the many in the ultimate nanny state of safe stimulus.

I need to up my game on my own blog. Too much soft cuddly soft, not enough incision.

Fascinating area. And very scary. Can’t wait for next year’s HowTheLightGetsIn festival at Hay, maybe there will be a session on the advances in this work-they should book you a slot Peter!

I couldn’t help but think of the Dr. Fox hypothesis in the context of the Scramblers (or rather, the species behind them but I can’t recall if they were actually ever given a designation to refer to them, even among the fans? The Rorcshakers?)… they get these communications from Earth, realize, “Hey, this stuff is clearly a communication from the stars, a vast undertaking, but it makes absolutely no sense… OH MY GOD THEY MUST BE BRILLIANT LET’S SEND A MISSION IMMEDIATELY AND LEARN FROM THESE PEOPLE.”

Of course, there’s no reason to assume they’d suffer the same cognitive drawbacks we do, so the “it’s an attack” explanation makes more sense (and is more thematically appealing within the novel) but I get a smile out of the mental image of Blindsight as being entirely the result of the Rorcshakers trying to contact their benevolent genius alien space brothers, and their inevitable disillusionment, nonetheless.

Peter Watts wrote: So I come away from this paper with mixed feelings. I like what they’ve done— at least, I like what I think they’ve done. From what I can tell the data seem sound, even behind all the handwaving and obfuscation. And yet, this is a paper that acts as though it’s got something to hide, that draws your attention over here so you won’t notice what’s happening over there. It has issues, but none are fatal so far as I can tell. So why the smoke and mirrors? It’s like being told a wonderful secret by a used-car salesman.

Maybe they’ve got a huge buttload of really interesting data that they want to look at for longer, before they publish, and this is the least they could get away with, so as to stake a claim with “first publication”? Perhaps this is intended to be the least they could get away with, without revealing more. That would be my guess.

[…] Watts of No Moods, Ads, or Cutesy Fucking Icons examines the flaws of a paper on a proto-Borg collective of […]

Peter D,

why do you think there is a species “behind the scramblers?” Isn’t part of the point of the book that there isn’t?

That’s not what I got out of it. They made the point that the scramblers themselves weren’t a species as we generally understand them, and that they and likely whatever sent them weren’t CONSCIOUS but were intelligent (my “OH MY GOD THEY’RE GENIUSES” was meant to be a humorous way to illustrate their non-conscious assessment not an indication that they actually think that way), but sooner or later you’ll get back to something that’s able to reproduce and there was the whole “Scramblers are the honeycomb, Rorshach are the bees”, then Rorshach might be the species, or another tool (a dandelion seed, which implies a dandelion species), but sooner or later you get back to a group of organisms (even if not DNA based) that reproduce and have evolved to a level that can use tools, that I’d call a species. Well, as I look back now, the “It’s an attack” speech did start with “Imagine you’re a scrambler”, so either now we’re declaring it a species and indeed, there’s no need to necessarily invoke anyone BEHIND them, we’re using the shorthand “scramblers” to describe both the waldos with teeth and the species behind them (which might be morphologically similar, much like we could theoretically create warrior clones to do our intergalactic wars) or they’re tools to some other species (Rorshach or otherwise), or it’s way weirder than I’m capable of grasping

Peter D,

After Echopraxia, I was under the impression that the category of phenomena which encompasses Rorschach, the scramblers, Portia etc. is the result of the proliferation of information directly through matter, much as we result from the proliferation of information through DNA. So everything we get to see is a manifestation of the same imperative. Might be difficult to define that in terms of “species” though. Perhaps it’s more akin to a physical state than to biology.

The graph formatting is atrocious, but I tend to use what I just learned is “Hanlon’s razor” in these circumstances: Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

In this case, I don’t think it’s really stupidity, just general laziness in formatting.

I’m an engineer, not a scientist, but you would be amazed by how many graphs and charts I see where the axes aren’t even labeled.

guildenstern42,

Yeah, my guess is that it’s actually just the result of someone trying to be clever in packing as much info into a single plot as they could – Nature’s page-length restrictions are severe.

And I don’t know what it’s like in other fields, but in mine (astrophysics) everyone has a good laugh over the description of Nature as “prestigious”, because they have such a long track record of publishing stuff that turns out to be wrong.

> Splice the code for the right kind of opsin into a mouse genome and the little rodent will be able to perceive colors she never knew before. These are abilities unprecedented in the history of the clade— and yet somehow, brains figure out the user manuals on the fly. Borg Collectives may be simpler than we ever imagined: just plug one end of the wire into Brain A, the other into Brain B, and trust a hundred billion neurons to figure out the protocols on their own.

I’m staring in confusion now, because I thought this was already well known, and yet I can’t find anything on it, so obviously it isn’t.

I could have sworn that ten years ago I was reading articles documenting how you can stick a new information channel into a brain and the brain adapts. Supposedly, fighter pilots using the same sort of HUD for long enough would start to experience a mild feeling of blindness when leaving the plane and a severe feeling of blindness if their HUD turned off in flight, and this is because they were losing a visual data channel, a channel which is separate from everyday “sight” in the sort of content it provides. There were other examples that I don’t recall, and investigation into what looked like the brain starting to grow new specialized modules for handling these new input methods, with recurring “this is a very promising field, and we look forward to future research on this topic” notes at the bottom.

But my searches for citations are not turning this up.

Maybe I confabulated the whole thing. I don’t have evidence, after all, only a vivid internal experience of feeling that much of the research was already done: yes, you can stick a wire into the brain and the brain will figure out what it’s receiving. The only tricky part is the sending, where you need a little more than a wire.

Surely the Dr Fox thing is just ego? An expert will naturally be very reluctant to admit that they don’t understand a portion of a paper in their field of expertise. And so gibberish survives the review process.

As for the generally poor writing in science, in my experience it’s a combination of young researchers trying to write like their supervisors (who may be terrible writers themselves) and English not being their first language.

WRT this paper, I agree that they might have done something really incredibly interesting, but it’s impossible to know for sure! The good thing is that the work will be repeated and expanded so over time anything of value will float to the surface.

Science moves slowly in part because of the appalling writing – that’s not necessarily a bad thing!

Have you considered the possibility that scientists expressing themselves in a 2nd language are going to express themselves ..oddly? None of the authors appear to be native speakers. Interesting though. This kind of research being performed in the US, by a team that seems to consist of a Portuguese, a Jew, a Russian and a Greek. Not sure where Ms. Chiuffa hails from..

Almost the entire department seems to be foreign-born, or of immigrant origin. But I guess that can be expected if you can recruit from anywhere. Interesting to note no black person there.

Anyway, but I believe you are onto something with Dr.Fox’s assertion. If a coating of turgid helps something seem more profound than clear, simple language..why would you expect scientists to spend extra time to express themselves clearly AND lessen their chances for success?

Also: consider perhaps that an opaque but truthful style of writing might make the readers think more about the subject, and requires them to build a better mental model of the subject in order to understand it…