Dumb Adult.

We didn’t have “Young Adult” when I was your age, much less this newfangled “New Adult” thing they coddle you with. We had to jump right from Peter the Sea Trout and Freddy and the Ignormus straight into Stand on Zanzibar and Solaris, no water wings or training wheels or anything.

Amazingly, I managed to read anyway. I discovered Asimov and Bradbury and Bester at eleven, read Zanzibar at twelve, Solaris at thirteen. I may have been smarter than most of my age class (I hope I was— if not, I sure got picked on a lot for no good reason), but I was by no means unique; I only discovered The Sheep Look Up when a classmate recommended it to me in the tenth grade. And judging by the wear and tear on the paperbacks in the school library, everyone was into Asimov and Bradbury back then. Delany too, judging by the way the covers kept falling off The Einstein Intersection. Back in those days we didn’t need no steenking Young Adult.

Now get off my lawn.

I’ll admit my attitude could be a bit more nuanced. After all, my wife has recently been marketed as a YA author, and her writing is gorgeous (although I would argue it’s also not YA). Friends and peers swim in young-adult waters. Well-intentioned advisers, ever mindful of the nichiness of my own market share, have suggested that I try writing YA because that’s where the money is, because that’s the one part of the fiction market that didn’t implode with the rest of the economy a few years back.

But I can’t help myself. It’s not that I don’t think we should encourage young adults to read (in fact, if we can’t get them to read more than the last generation, we’re pretty much fucked). It’s that I’m starting to think YA doesn’t do that.

I’m starting to think it may do the opposite.

Hanging out at last fall’s SFContario, I sat in on a panel on the subject. It was populated by a bunch of very smart authors who most assuredly do not suck, who know far more about this YA than I do, and whom I hope will not take offense when I shit all over their chosen pseudogenre— because even this panel of experts had a hard time coming up with a working definition of what a Young Adult novel even was (beyond a self-serving marketing category, at least).

The rules keep changing, you see. It wasn’t so long ago that you couldn’t say “fuck” in a YA novel; these days you can. Back around the turn of the century, YA novels were 100% sex-free, beyond the chaste fifties-era hand-holding and nookie that never seemed to involve the unzipping of anyone’s fly; today, YA can encompass not just sex, but pregnancy and venereal disease and rape. Stories that once took place in some parallel, intercourse-free universe now juggle gay sex and gender fluidity as if they were just another iteration of Archie and Betty down at the malt shop (which is, don’t get me wrong, an awesome and overdue thing; but it doesn’t give you much of a leg up when you’re trying to define “Young Adult” in more satisfying terms than “Books that can be found in the YA section at Indigo”).

Every now and then one of the panelists would cite an actual rule that seemed to hold up over time, but which was arcane unto inanity. In one case, apparently, a story with an adolescent protagonist— a story that met pretty much any YA convention you might want to name— was excluded from the club simply because it was told as an extended flashback, from the POV of the protagonist as a grown adult looking back. Apparently it’s not enough that a story revolve around adolescents; the perspective, the mindset of the novel as artefact must also be rooted in adolescence. If adults are even present in the tale, they must remain facades; we can never see the world through their eyes.

Remember those old Peanuts TV specials where the grownups were never seen, and whose only bits of dialog consisted entirely of muted trombones going mwa-mwa-mwa? Young Adult, apparently.

Finally the panel came up with a checklist they could all agree upon. To qualify as YA, a story would have to incorporate the following elements:

- Youthful protagonist(s)

- Youthful mindset

- Corrupt/dystopian society (this criterion may have been intended to apply to modern 21rst-century YA rather than the older stuff, although I suppose a cadre of Evil Cheerleaders Who Run The School might qualify)

- Inconvenient/ineffectual/absent parents: more a logistic constraint than a philosophical one. Your protagonists have to be free to be proactive, which is hard to pull off with parents always looking over their shoulders and telling them it’s time to come in now.

- Uplifting, or at least hopeful ending: your protags may only be a bunch of meddlesome kids, but the Evil Empire can’t defeat them.

Accepting these criteria as authoritative—they were, after all, hashed out by a panel of authorities— it came to me in a blinding flash. The archetypal YA novel just had to be— wait for it—

A Clockwork Orange.

Think about it: a story told from the exclusive first-person perspective of an adolescent, check. Corrupt dystopian society, check. Irrelevant parents, check. And in the end, Alex wins: the government sets him free once again, to rape and pillage to his heart’s content. Admittedly the evil government isn’t outright defeated at the end of the novel; it simply has to let Alex walk, let him get back to his life (a more recent YA novel with the same payoff is Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother). Still: it failed to defeat the meddlesome kid.

So according to a panel of YA authors— or at least, according to the criteria they laid out— one of the most violent, subversive, and inaccessible novels of the Twentieth Century is a work of YA fiction. Which pretty much brings us back to 11-year-old me and John Brunner. If A Clockwork Orange is Young Adult, aren’t that category’s boundaries so wide as to be pretty much meaningless?

But there’s one rule nobody mentioned, a rule I suspect may be more relevant than all the others combined. A Clockwork Orange is not an easy read by any stretch. Not only are the words big and difficult, half of them are in goddamn Russian. The whole book is written in a polygot dialect that doesn’t even exist in the real world. And I suspect that toughness, that inaccessibility, would cause most to exclude it from YAhood.

In order to be YA, the writing has to be simple. It may have once been a good thing to throw the occasional unfamiliar word at an adolescent; hell, it might force them to look the damn thing up, increase their vocabulary a bit. No longer. I haven’t read a whole lot of YA— Gaiman, Doctorow, Miéville are three that come most readily to mind— but I’ve noticed a common thread in their YA works that extends beyond merely dialing back the sex and profanity. The prose is less challenging than the stuff you find in adult works by the same authors.

Well, duh, you might think: of course it’s simpler. It’s written for a younger audience. But increasingly, that isn’t the case any more, at least not since they started printing Harry Potter with understated “adult” covers, so all those not-so-young-adult fans could get their Hogworts fix on the subway without being embarrassed by lurid and childish artwork. The Hunger Games was first recommended to me by a woman who was (back then) on the cusp of thirty, and no dummy.

All these actual adults, reading progressively simpler writing. All us authors, chasing them down the stairs. Hell, Neil Gaiman took a classic that nine-year-old Peter Watts devoured at age nine without any trouble at all— Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book— and dumbed it down to an (admittedly award-winning) story about ghosts and vampires, aimed at an audience who might find a story about sapient wolves and tigers too challenging. It may only be a matter of time before Nineteen Eighty Four is reissued using only words from the Eleventh edition of the Newspeak Dictionary. We may already be past the point when anyone looking to read Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea looks any further than the Classics Illustrated comic.

I know how this sounds. I led with that whole crotchety get-off-my-lawn shtick because the Old are famously compelled to rail against the failings of the Young, because rants about the Good Old Days are as tiresome when they’re about literacy as they are when they’re about music or haircuts. It was a self-aware (and probably ineffective) attempt at critic-proofing.

So let me emphasize: I’ve got nothing against clear, concise prose (despite the florid nature of my own, sometimes). Hemingway wrote simple prose. Orwell extolled its virtues. If that was all that made up Young Adult, even I would be a YA writer (at least, I don’t think your average 16-year-old would have any trouble getting through Starfish).

But there’s a difference between novels that happen to be accessible to teens, and novels that put teens in their heat-sensitive, wallet-lightening crosshairs. I know of one author who had to go back and tear up an adult novel, already written, by the roots: rewrite and duct-tape it onto YA scaffolding because that’s the only way it would sell. I know a very smart, highly-respected editor who once raved about the incredible, well-thought-out plotting of the Harry Potter books, apparently blind to the fact that Rowling— her claims to the contrary notwithstanding— seemed to be just making shit up as she went along.[1]

A long time ago, a childhood friend named Stuart Blyth gave me the collected tales of Edgar Allen Poe for my tenth birthday. I loved that stuff. It taught me things— made me teach myself things, in the same way a Jethro Tull song a few decades later forced me to look up the meaning of “overpressure wave”. I have to wonder if YA does that, if it improves one’s reading skills or merely panders to them. I doubt that your vocabulary is any bigger when you finish Harry Potter and the Well-Deserved Bitch-Slap than when you started. You may have been entertained, but you were not upgraded.

Of course, if entertainment’s all you’re after, no biggie. The problem, though, is that it acts like a ratchet. If we only allow ourselves to write down, never up— and if the age of the YA market edges up, never down— it’s hard to see how the overall sophistication of our writing can do anything but decline monotonically over time[2].

Who among you will tell me this is a good thing?

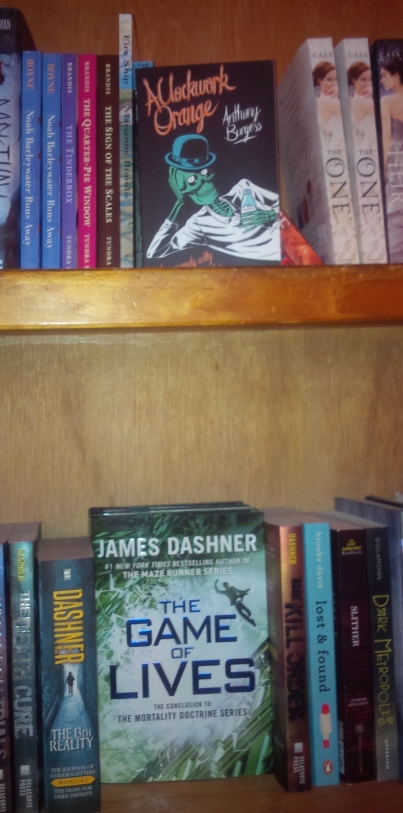

Late-breaking edit, 22/03/2016: Courtesy of “Damon”, about whom I know very little except that he’s chosen an awesome ISP, Teksavvy, which puts him somewhere in my end of Canada. Apparently his buddies in the local bookstore have taken my insights to heart, and rearranged the YA section thusly:

My work here is done.

[1] I mean, think about it: we have a protagonist whose central defining feature is the murder of his parents when he was an infant. And when he discovers that time travel is so trivially accessible that his classmate uses it for no better purpose than to double up her course load, it never once occurs to him to wonder: Hey— maybe I can go back and save my parents! This is careful plotting?

[2] This was one of the points I was trying to make a few weeks back when I announced my retirement from the word of adult fiction, and my new career as an author of stories written exclusively for preschoolers. That post was satirical, by the way, although I’m grateful to all of you who wished me well in my new endeavor.

I read A Clockwork Orange before I saw the film version (in college as a junior). As an English major and logophile, I found the novel compelling, unsettling and very well written. While walking back to my dorm after the film, I became so nauseous I nearly puked. There’s one particular scene that caused that reaction. I will never watch that movie again, and it’s very unlikely I’ll re-read the novel because, for me, it’s been poisoned by the images in that scene.

I disagree with your categorization of ACO as YA. It may, in your view, fit that list from the panelists but, because of the unrelenting violence of Alex and co. as well as the state, the novel overall is an intensely depressing read. The boundaries between YA and adult fiction have indeed become blurry, but they haven’t disappeared. In the YA I’ve read, one can cheer for the kids; ACO elicits no such reaction.

Just my two cents. Hi, btw. 😉

I read the first Harry Potter novel in about two hours and thought”Well, this is simplistic bullshit”. Shows how much I know.

Though I agree with the empirical claim of this post (YA is defined by simpler language and is less cognitively challenging), I’m not so sure that I see this as a ‘problem.’ Though I’m as sensitive to the appeal of literature as the next person (did a PhD in it back in the day, and am a scribbler manqué), I wonder nowadays if the value we assign to literature is just a case of pre-reflective capture by an artefact that happens to super-stimulate our cognitive systems. If it’s not that, it could be just as easily be a useful totem that allows us to signal affiliation to the clique that we believe we belong to (i.e. the thuper-duper clever people who really know the score).

Sure, it can be argued that literature that does something that other representational forms don’t. For instance, there’s Bal and Veltkamp (2013)’s and Kidd and Castano (2013)’s results on literature improving empathy. However, longer improvements of empathy have been shown to emerge from the deciedly more déclassé activity of identifying with a superhero.l Equally, in some soon-to-be unpublished work by my own group, we find that propensity to be captured by literature scales with anxiety, depression and absence of meaning.

What point am I making? I guess it’s that literature––understood as a proxy for ‘quality’ or ‘sophisticated’ writing––may well be like one of those parasites that convince their hosts that they want to be parasited on.

I’m puzzled by the idea that “corrupt/dystopian society” should be a defining characteristic of YA.

I realize that it’s a nearly-ubiquitous _trope_ in contemporary YA. But it seems of a different kind from the other criteria listed. Is it impossible to tell a good story from the viewpoint of and for adolescents, without including an Evil Tyrant Who Must Be Defeated? Do aspiring YA authors who fail to include the requisite dictator get sent back and told to try again?

I realize you need a good antagonist and nothing satisfies like overthrowing a tyrant. I realize that President Snow or whoever is just a surrogate for mom and dad who are being, like, _so_ unreasonable. Still, the idea that one increasingly hackneyed trope should be set up as a defining characteristic is almost as disturbing as the dumb-it-down-as-far-as-possible-and-then-some trend.

So I recently picked up a novel by one certain Jane Austen. I didn’t even know the genre, let alone the date of first publication. I had just come across the title “Pride and Prejudice” one time too many to just move along, so I wondered what all the fuss was about. And my mind was blown. I am no native English speaker, yet I was able to follow along with the amazing and complex prose because the intended meaning was always clear from context. I have never so much enjoyed characters ripping into each other with such gleeful rudeness before. Not least because I am a scarred child where major plot points revolving around characters refusing to communicate properly are concerned. (Harry Potter, I am farting in your general direction.) No such blame can be laid at Austen’s feet.

Anyway, my points are the following: The ease with which I can look up unfamiliar words on my ebook reader has so far prevented me from ever dropping a book because I couldn’t follow the prose. I learned English as my second language using Harry Potter, mostly because I had gobbled up the first two books and the third hadn’t been translated yet, so thirteen-year old overconfident ADHD-me went off on the deep end and bought the English version. I ended up nicking an OALD from the school library and via Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett I soon graduated to classic SciFi. Asimov, Bradbury, Clarke, I even read Lem in English because I didn’t know any better. I don’t know if my own experiences are in any way representative of the young adult experience but I think the point is this: There is nothing inherently wrong with dumbed-down prose to reach a YA target audience. Most of them just do not know how to read with enjoyment yet. Most have actually been negatively biased by having to read weird stuff like “Catcher in the Rye” or “Moby Dick” in school. (Both are undoubtedly good books but you have to be able to _chose_ to read them.) I don’t think Harry Potter, Hunger Games etc are doing a disservice to readership as a whole by being simple prose yet thoroughly engaging. (Let’s leave Twilight out of it, shall we?)

My second point is that the classics are not going to go away. I may be weird in the way I make a point to _not_ look at a publication date before deciding to read something but I have the feeling that most books get bought via recommendations instead of bestseller lists.

And last but not least, I don’t imagine Peter (is able) to dump down his prose any time soon.

PS: And I just moved Edgar Allan Poe into my to-read list to find out what all the fuss is about. Cheers 🙂

Perhaps YA is the 21st Century’s equivalent of Pulp fiction. Ripping tales of high adventure. In which case the market is big enough to sell YA and Adult, whatever Adult fiction means in this context. The problem is then the publishers who are unable to see the woods for trees because the accountants rule – the bottom line Trumps all.

I wouldn’t give in to despair just yet. If you look in other industries where the primary draw is some degree of escapism, the nature of the beast looks to be cyclical. For two decades, competitive pressure commanded Triple A developers of video games to further and further lower the challenge and skill level of their titles while compensating with flashier visuals and a proliferation of increasingly meaningless player choices to max out the hardware and pad out review paragraphs. Then Dark Souls hit the scene within the last few years like a excruciatingly overweight mace to the back of the head, and demonstrated that the murmurings of discontent on the internet had grown with time into a sizable market of status-seekers whose greatest desire was to segregate themselves from the plebeians, and blundered into skill and elevation of such while pursuing this desire as a byproduct.

Frankly, the idea that your diversionary material should be an exercise in self-improvement isn’t a new one. We’ve heard that bitter tsking constantly from the ivory towers of Literature. Of course, when they did it, it was an appeal to the Dark Ages of Obscurantism and abstruse High Culture, yes? We exclusively were the ones that had a monopoly on practical Aesops, the human condition, and relevant critical thinking. What did Sinclair Lewis say? “It can’t happen here”?

From my perspective, the Young Adult phenomenon is the latest incarnation of the struggle between emotion and information, where the purest evocation of emotion might be a surprise birthday party, and the purest expression of information might be a textbook chapter on the Deutsch Limit written entirely in Ithkuil. The long, twilight struggle between first the epic and the novel, and then between genre fiction and literary fiction, points to the conclusion that when forced to choose between what in which their amygdala finds merit and what in which the intelligentsia does, the one that releases the dopamine pulls ahead almost every time.

Here’s a decent takeaway: information density is an asset when it pulls on the subconscious as much as it does awareness. Life Of Pi might have been a literary smash hit that renewed Maclean’s hope that the hoi polloi were finally “getting it”, but I’d bet my bottom rupee that it owes most of its popular success to poking the populace’s ‘spirituality’ and ‘sublimity’ buttons. Likewise, while Blindsight taught me Icarus-loads about undistinguished yet brilliant science (science so brilliant that it would shock me if it didn’t play a major role in the upcoming century), that information most likely sticks in my hippocampus because it was synthesized into a cognitive prototype that was existentially terrifying.

A final digression:

I also recall breezing through works like The Lord Of The Rings in the summer break between the second and third grade, but then, upon returning to those novels in my teenage years, they were noticeably denser and sometimes even a slog. I blame it on “Semiotic Baggage”: as humans age, their brains come to associate denotations more solidly with an increasing morass of connotations, until the prefrontal cortex spends so much of its energy recognizing connections and unpacking (optional) information that it restricts itself to the digestible just to get some relief. Reading a work of fantasy, science fiction, or horror basically becomes an act of cognitive dissonance.

Perhaps the best means of circumventing it might be to drop the concept of Readability Levels entirely, and encourage young children to expand their reading material up to the college level early on, when the nerves are still plastic and semantics easily skimmed, before having them return for critical analysis at the close of Secondary Education.

Here is a partial list off the top of my head of the books I remember being required to read in school: A Separate Peace. Wuthering Heights. To The Lighthouse. Great Expectations. A Tale of Two Cities.

I note now that this list of books I was required to read in school is, in fact, a list of the books I avoided reading in school, by accepting very low or failing grades in English. I do not think that acceptance of horrible grades is what I was supposed to be learning.

Wuthering Heights, I have learned to enjoy in my later years. The others, pfft. I still can only be made to read Dickens under duress. Knives are probably required.

I am certain that there were many other books I was require to read. But I don’t remember any of them, because they neither engaged nor distressed me. I only remember the ones that defeated me.

There was also at least one Shakespeare play each year. I mostly enjoyed those, and remember bits and pieces of them. I never got assigned Hamlet, though, because that was only for “Honors” English. I was just “Regular” thanks to too many poor grades in English.

Need I note that I probably read well over 400 books on my own just during high school (grades 9-12)? Not just SF either; there was a goodly percentage, at least 15%, of science non-fiction and even non-curricular math textbooks.

My point?

Secondary school English education, in the USA, is broken beyond belief, and likely beyond hope.

//It may only be a matter of time before Nineteen Eighty Four is reissued using only words from the Eleventh edition of the Newspeak Dictionary.//

Actually, that could be great, from the point of view of being fully immersed into the world, ala Clockwork Orange.

Even better, create a different version of Newspeak (with new words so that people already familiar with blackwhite and duckspeak won’t be clued in too quickly), write a story from the point of view of a prole or Outer Party member just in Newspeak, and see if you can get the majority of your readers to fail to notice that something horrible is going on, obscured by the language.

“Who among you will tell me this is a good thing?”

I shouldn’t have thought it necessary to tell you, or to explain why. I would have thought it was obvious.

The approach you appear to be advocating is to permit our young (and let me remind you that the age of adulthood in ancient Rome was 25) to read novels containing vocabulary and ideas, with which they may not be familiar. You do realize that this will require those who persist in reading a novel that is beyond their current experience to seek out definitions, decode unfamiliar constructions, and grapple with novel ideas, do you not? Have you not read Genesis? No good has ever come from eating of the fruit of knowledge, only despair and pain. Why on earth would you want to allow people to read works that recast their shadow with a light that shows them to exist on a vaster, more variegated, plane? Do you not see the danger? When a light is cast, and a person sees more than they previously did, they ask questions not only about the unknowns that they can now see more clearly, but the unknown unknowns that they did not previously know existed. Surely you can see where this leads, and that no good can come of an addiction to knowledge. Once they can see new questions, they will seek answers to those questions, and in so seeking discover yet more questions. Is it this madness of the junkie that you would wish upon our children?

I suppose this trend in literature that you describe (and scorn) may not be a good thing, if you think seeking knowledge in a world that has boundaries on reason and empirical information is a worthwhile pursuit. The fact that empirical evidence cannot be sought beyond the boundaries of space and time, and that all arguments are ultimately circular, contingent on premises that one must accept on faith whether one realizes that that is what one is doing or not, renders the pursuit of knowledge essentially a meaningless, self-serving form of mental self-abuse tantamount to that activity responsible for the blindness and hairy palms of so many of those who walk among us. Only a faithful acceptance of the mindful shepherding of our rightful leaders will save us from the fate awaiting the hopeless addict. The move toward novels rendering the complexity of this world into a more accessible and less harmfully ambiguous reconstruction, reconstituting the razor crystals of this world into graspable forms, can only be good for humanity. Those who read works that at their core pose questions even about the works themselves (yes, I’m looking at you John Fowles) learn to question themselves, and a honed question can be a fearful weapon. Our economies, our governments, our freedoms, depend on avoiding this theatre. We are on the right path, here, shaping the ideas that will allow us the freedom to live in peace.

This of course, applies to all of us, and why the movement of what has been considered “adult fiction” into the more wholesome form, that you decry, is good for humanity in general. But we must not forget the children, where this project started, and who most deeply benefit from it. Allowing them to read as children did in days of yore will create children who know more and think more deeply than their peers. When they then have the temerity to point out the limitations of their compatriots, can you blame those classmates for reacting violently when their shortcomings are exposed? The blood of these enlightened readers will be on your head if this YA trend in literature is curtailed. None of us wants that. There is a way to end school yard bullying, it’s there in the form of YA, and it is irresponsible not to accept it as the solution.

You’re gonna love Randall Munroe’s Thing Explainer then

“The titles, labels, and descriptions are all written using only the thousand most common English words. Since this book explains things, I’ve called it Thing Explainer.”

As a writer for children and as a fan of your work, this is pretty much horseshit. If anyone else made such rot-of-culture pronouncements based on such a tiny, miniscule, reading sample and one panel, you would laugh heartily at them. Heartily, I say. Hey, you know who was an adult bestseller when harry Potter was coming out? Dan Brown! Nobody was ashamed to be seen reading him! Nobody needed special covers! And yet.

Me, at age of 12, I went straight from reading Enid Blyton and Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys to Tolkein! And thence to Terry Brooks! David Eddings! Challenging stuff! They upgraded the shit out of me! No pandering there! Now the poor spoiled pandered children have to make do with dross like Philip Pullman and Margo Langan! Wretched downgrading simple unchallenging stuff! When the standard is going from Bertie The Budgie to in Search Of Lost Time at the age of seven, and we have Austen, Kipling and Verne, literally no other book need ever be written for children because those will tell them literally everything the need to know about the experience of growing up in the 21st century.

Also, along with all the other elements she deployed rather skilfully, Rowling included rather well-plotted whodunnit elements in the first three Harry Potter novels. Her prose grew increasingly serviceable as the series went on, but she’s a terrific storyteller. Better than Dan fucking Brown.

Meanwhile, you have Kevin Crossley-Holland, Ann Halam, Thomas Andersen, any of whom I’d put up against any challenging adult writer you’d care to mention. Oh, sorry, Ann Halam is also Gwyneth Jones, an SF writer out to make a quick lucrative YA heap.

As for a definition of YA – it’s not a sodding genre, it’s an age-group. It includes EVERY genre, so genre definitions are beyond useless. I understand the impulse, when challenged for a genre definition of YA, to fall back on the characteristics of the books you write or the books you enjoy, but that list is for the birds, as you quite rightly show. YA books are books aimed at readers who are not yet adults. That the boundary blurs as YA and adultget closer is a feature not a bug.

John Boyne, Robert Cormier, Caroline Lawrence, Roddy Doyle, David Almond, Michael Morpurgo, the recently deceased Louise Rennison (to name a tiny, tiny fragment of the writers involved) all write YA to which that list only coincidentally overlaps, if it ever does. You’ve read Poe and Verne and Kipling but you haven’t read any of these writers yet feel confident in expressing the opinion that the sophistication ratchet is only going backwards? In assuming that a child will never encounter new vocabulary in any of these books? For shame. That’s disgraceful.

You may, as do many, reflexively deride YA as a marketing category, oblivious to the realty of the target audience, which is a growing, developing bunch of variegated humans who mature at different rates and experience wildly different social, family and educational lives and who develop as readers at different rates, whether it’s in terms of literacy or taste or interests or the ability to handle challenging subject matter. The vast, and i do mean vast, variety of approaches to prose and subjects within YA reflects the fact that for many readers there is a gradual handing off of responsibility for choosing reading material from parents and teachers and librarians and booksellers to themselves, and the various subcategories in terms of age-related reading is a valuable and useful guide for all concerned.

Sorry. I feel better for that rant. I think you’d write an awesome YA. Clive Barker toned down the sex and violence in his work when he wrote Abarat without sacrificing his actual writing or the ideas – there’s a discipline and a skill involved that made the book shine, the best thing he’d done in years. Terry Pratchett managed to convey the same humanist ideas in his YA books as he did in his adult books, Lemony Snicket’s All The Wrong Questions is a noir pastiche that manages to end on a note of loss loneliness and heartbreak. Older YA in particular is full or dark, painful books that do not necessarily end happily.

And Phil Estin with your shallow self-congratulatory satire: feck off. While you’re wallowing in smugness, older teens are reading Louise O’Neill. Please do read Only Ever Yours and Asking For It. There’s a terrible danger they may render your more accessible and less harmfully ambiguous understanding of YA into something more complex, and as you say yourself, that might get you beaten up or something.

I distinctly remember my nerdy friends and I reading The Clockwork Orange when we were 16-17 years old. Does this classify as Young Adult? I guess it does. I think it made a much larger impression on me than it would’ve done if I read it a couple of years later. Also, interestingly enough, the part of the book that we liked the most were the very extensive translator notes about challenges of coming up with faux-Russian swearwords.

I turned out fucked up like hell, but I doubt it was the book’s fault.

Anyway, I think you could push anything, apart from straight-up porn, as a YA novel as long as it’s got an adolescent main character. Make Ciri Keeton et al. into a bunch of teenagers et voila, “a heady read for a new generation”. Tons of Sarasti fan-art on DeviantArt, homoerotic fanfics, you name it.

Joe Abercrombie’s take on writing YA, for what it’s worth…

http://www.joeabercrombie.com/2014/03/10/he-killed-the-younglings/

Oh Nigel, stop bloody sulking – you’re all over the place.

“As a writer for children…”? Right. So that’s *not* YA, is it. That’s Children’s Fiction. Now how about we all grow the fuck up and start calling things what they really are.

The truly pernicious factor in YA is that it exists as a category at all. It’s a label designed to patronise and to coddle – “Oh hey, we’re not saying you’re a *child*. No, no, you’re such grown up big boy you’re a *Young Adult*. And we made all these books *especially for you*. So you won’t have to strain your little head.” In short, it’s the creeping infantilisation of late stage capitalism, writ large across the publishing industry’s forehead in dayglo marker.

The books themselves – *shrug* – almost irrelevant to the argument. They’ll be good, bad or indifferent, just like books in general. Some will carefully toe the recommended-content line in hopes of securing the market, some will end up dumped into the YA bin because they happen, coincidentally, to tick the right boxes. But none of this will change the fact that there are books for children, which are written in a curated fashion to cater to the children they are intended for, and there are books for adults which are not. There is no third category, and we do our children a grave disservice in trying to pretend there is.

Actually, Publishers Weekly just had a report from the Bologna Children’s Book Fair saying that dystopias have become passé. So one YA stereotype might be dying off. 😉

But is the rise of YA really any different than the superhero comic books I used to obsess over?

Hi, Richard. I think we once had a nice e-mail interview when your Black Widow series came out. Big fan. You’re talking absolute bollocks.

Well, I suppose I was all over the place with my response – sorry about that, but Jesus, grown-up men and women don’t half talk shite when it comes to children’s books. By the way, I describe myself as a children’s writer because my work has mostly been for mid-grade (that’s roughly 8-12, a distinction rightly meaningless to anyone until they do a primary school visit and stand before various classes of different ages and have to choose which stories and excerpts to read and hold their attention – then it suddenly matters a lot) but I has aspirations to write for both older and younger. Almost as if different age groups within the rather large section of the populace covered by Children’s Books require different approaches.

I do acknowledge that the big thing about people opining on YA as a category, particularly in response to a blog-post that argues, based on almost no reading in the area at all, that it is in the process of dumbing-down the reading public, is that the books themselves are almost irrelevant. People outraged at the existence of YA as a category don’t seem to particularly give a shit about the books contained therein. They haven’t read them but they’re pretty damn sure they’re infantilising and dumbing down and working the sophistication ratchet backwards. Children whose reading faculties spring fully formed from the brow of Zeus need no guidance and gradations when it comes to books, and let the rest founder as they may.

My own feeling is that the fact that it exists as a marketing category is irrelevant. Seriously who gives a fuck? (Except that I worked as a bookseller long enough to know I laugh in face of anyone who thinks that categories and sub-categories of books should be done away with.) What is relevant, to me, anyway, is the books, the reading, and the kids getting the books and doing the reading. The category of children includes infants. The process of growing to adulthood is moving away from infanthood. The process of becoming a reader and developing as a reader is the same. People develop at different rates, have different tastes which, in this day and age, can be explored freely and widely by teens in the category of YA. YA isn’t a marketing niche, it’s a microcosm. From one point of view it’s a microcosm of all the marketing niches that, if they infantilise children, surely infantilise adults, though I think to suggest as much is a grotesque insult to both. From a more useful point of view it is a microcosm of most of the reading opportunities available. And it is not fixed. It is fluid and there is overlap, which seems to cause no end of trouble for people who think that if categories exist they must be rigidly defined and enforced.

My point is, that if calling a category YA is infantiising, then so is the division or sub-division of any process of growth or maturing or education, which seems counter-intuitive to me.

So, disservice? No, they are a service. To adults who care for children and, as they grow, to children themselves. I mean I get that I’m suppose to care more about evil marketing and capitalism, but I just don’t. Kids have more and wider reading material available to them than when I was growing up, and the space to find and explore them, and that is flipping awesome. (I think you’d write a terrific YA book, too. Jesus, an SF YA written with your style and sensibilities? The shelves would explode.)

Joe Abercrombie’s YA books (not sure they were marketed YA in the US but they were over here) are great, and an example of what a writer can do without sacrificing any of their own distinctive sensibilities. He seems to get YA as a category, too.

Many superhero comics are YA – Ms Marvel won a Hugo! YA is FULL of stuff for kids to obsess over. I also suspect that YA dystopias will be with us for a while, albeit in different forms. It’s just the zeitgeist of growing up in a surveillance state besieged by terrorism, plagued by economic collapse and on the brink of ecological catastrophe.

Nice to see a shoutout to The Seep Look Up. John Brunner was possibly the greatest science fiction writer around back then and Sheep is the best one of his books. The ending with the talk show while life falls apart and the “That smoke is coming from America” line still gives me chills just thinking about

It had a weird public reaction, for sure. Kubrick actually asked that it be withdrawn from circulation in the UK, because kids were starting to explicitly adopt Alex as a role model.

For my part, when I finally caught the movie (it was banned outright upon release in the province of my birth), I found it almost abstract. The violence was so stagey and choreographed that it seemed almost balletic.

I thought that for the first couple of books, and then it started to win me over. The trick was to not regard the books as novels in themselves, but rather as chapters in a bigger epic. The first book, taken in isolation, is childish wish-fulfillment crap about a bullied schoolboy who Learns He Is Special, and has superpowers, and was rich and legendary and important all along. And kicks ass at everything he tries without trying. As the series progresses, though, you discover that that was only set-up for a huge fall; Harry basically becomes a burnt-out Viet-Nam vet, vilified and harassed. When I saw that happening, I thought “Cool!”.

But by the back half of the series, there were so many gaping plot holes opening up that Rowling squandered all the good will she’d engendered.

That’s kind of an interesting perspective. (I used to wake up my Monday morning Animal Behavior class by arguing, similarly, that top-40 singles were literally alive, at least as much as viruses were.

@Nigel

Yeah, you’re still broadly missing my point. You write children’s fiction – good for you – and even better, you call it what it is. Happens to be in the age range 8 – 12. Fine. I’m all in favour of age banding for parental use (though not in big bright numbers on the spines of books, which is, I’d agree with Pullman et al, a limiting rather than an enabling strategy). But why is it exactly that once that same children’s fiction is being written with teenagers in mind, it suddenly has to be called Young Adult? Teenagers are not adults – why do we need to flatter them that they are? It’s deeply patronising.

Instead, why not be honest with them – tell them, look, you’re still reading fiction for kids, but it’s for kids your age. Enjoy! And if you don’t like that – you feel you’re way mature for *kid’s stuff*, then, hey, over there you’ve got the adult stacks; dive in, why don’t you – give it a shot. Might be a challenge in places, but that’s all part of the fun! Enjoy!

One of these strategies encourages exploration, independence and maturity. The other is this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yo9_aBj1Z84

Me too. At the time, I just deferred to the authority of the folks who wrote the stuff.

That’s actually kind of inspiring.

But my point is, there’s no inherent need to. I think much of the dumbing-down is needless, and ultimately destructive insofar as if you’re only ever fed a diet of porridge and peaches, you may never develop a taste for solid food. And that’s what we’re seeing as more and more not-so-young adults keep reading YA titles.

For me, it was discovering what a “morgue” was. Also what orangutans were.

Hey, I’ve got Dark Souls. I’ve had it for years. I swear I’ll get back to it. Right after Fallout 4.

No, not an exercise! You make it sound onerous! Do you really think I sat there in an Oregon basement forcing myself to read Solaris even though it was dry as sawdust, because my 13-year-old self felt some grim determination to better his intellect? I read it because it was cool, because it sucked me in! I read it because I wanted to!

And I think it would suck in a lot of other 13-year-olds, too. Even if some of it went over our heads.

There’s a story in there somewhere…

Yeah. I think you’re right.

Maybe in Canada too. I don’t know. But I read a lot over the summer too. And I read a lot in class, when I was supposed to be doing other things. Teachers complained about that on my report card.

My sense is that we shouldn’t allow formal education to keep us from learning stuff.

Well, possibly. The YA tag annoys you, I just don’t find the rationale for the annoyance convincing. In particular I don’t think you’re giving kids enough credit. In my experience they’re pretty savvy about their own reading levels and their likes and dislikes. They know the stuff they read is for kids, they know there are gradations within the stuff aimed at kids, and they know there’s an upper end where the kid/adult stuff blurs together. I’m pretty sure that as they grow most kids don’t need much prompting to go hunting in the adult stacks.

The tern YA has been around for a long time, but it came into general use because the children’s section in most bookshops was growing to unmanageable proportions. The children’s book market is huge, and overcrowded, and most bookshops just don’t want to stock Baby Goes Potty next to Sexy Dystopia Of The Blood Monkeys. At least they didn’t call it BukZ 4 TeenZ. Wif a ‘Z!’

ps – that comment about the infantilisation process of late stage capitalism is not meant to carry ponderous good vs evil moral tones – it’s a simple statement of fact. Late stage capitalism, having satisfied more basic needs, is driven inevitably to seek to satisfy increasingly non-essential desires. Over time that means discouraging effort or exertion in consumers in favour of handing them easy options and escalating levels of comfort. It applies as much to food – ready meals and snacks vs actual cooking – as it does to prose fiction.

As for YA and superhero comics – fucking tell me about it 🙂 I was flabbergasted when I wrote for Marvel and found myself fenced about with a thicket of “thou shalt nots”, and worse still a readership contaminated with Stepford Readers who concurred fully with those limits. Most fucking stupid thing I’ve ever been faced with in my career as a writer – if that’s writing YA, then no thank you very much.

Hm, I think a previous comment was lost because I am an idiot. What it boils down to is this – I think I really do not get objections to Young Adult or YA as a phrase. To me, and, I think, to anyone involved in the trade and I suspect the kids as well, it’s just a term of art referring to a specific albeit broad category of books for certain ages. That’s it. Other connotations, whether it be patronising or efforts to get down with the kidz are a bit lost on me, so when people object I assume they’re, I don’t know, objecting to the existence of categories within children’s fiction full stop? I do agree about the bright numbers on the spines of books. That was a stupid proposal.

I still think Peter Watts is very wrong about what goes on within the category, but that’s a different issue.

Welcome, Nigel. Great rant. Good points. Some of them, anyway.

En garde.

Okay. The fact that I only listed three YA authors doesn’t mean I’ve only read those three. There’s Rowling, of course (who probably comprises half the YA field right there, if your metric is the sheer tonnage of books sold). There’s Livingston. Hell, there’s my wife, who’s been classed as a YA author and whose oeuvre I’m pretty familiar with. And let’s not forget, that “one panel” consisted of five YA authors, who presumably know a fuckton more about the field than I ever will. I’m not pretending any kind of expertise here; I’m merely channeling it.

Also, implying that criticizing YA is somehow tantamount to defending Dan Brown? Kind of a stretch, dude.

Oh, she even won me over with the setup, once I realized where she was going. It was only when she actually got there that I realized she’d lost the map.

And what is it with you and Dan Brown? Did he beat you as a child or something?

Dude, this all feeds exactly into my point! The good, solid dark “YA” (I’d include Caitlin Sweet’s work among it) can be enjoyed just as much by adults as, say, The Stars My Destination or The Martian Chronicles can be enjoyed by adolescents. So with that kind of leakage, what the hell is the point of even having a YA category?

You almost said it yourself. It’s not a genre, sure enough, but it’s not an age-group either, not when so many 40-somethings are reading Harry Potter. It’s a maturity-group, or a literacy demographic, or something. Whatever it is, it ain’t natural: it’s a marketing artefact. I got no problems with adults who get off on His Dark Materials; what I take issue with is when authors are told to take a book that already works just fine on its own, and retcon it to suit a classification so diffuse that all the good stuff leaks across its boundaries in both directions anyway.

When agents tell their clients to dumb down their work to fit into some Platonic cookie-cutter ideal, the problem isn’t with the author. The problem is with the template.

(PS. And remember: I didn’t invent that template. I just copied it down from folks who know what they’re talking about.)

Hey Richard. Always nice to see you wade in.

You guys, you’ve all heard about Altered Carbon getting turned into a big-budget miniseries, right? Way to go, Richard.

Fucker.

Sheep is one of the two most influential books on my life. (The other was A Whale for the Killing. Since you were wondering.)

🙂

Thank you, Peter – heh, I wondered if I’d set myself up there.

No, I don’t think you were defending Dan Brown (he did make my inner child cry) but when the vogue for new covers on Rowling’s books occurred there was a lot of pushback and sneering, deserved to some extent, because it was a bit silly, but at the same time the bestselling adult books were by Brown and I’d rather read a hundred Rowlings than a single Brown, and I was never embarrassed by the cover. I guess my point was, judging children’s fiction by Rowling is like judging adult fiction by Brown. Which, if you did, children’s fiction would come off better.

It’s purely practical. Children’s books is huge. Overstuffed and overcrowded with titles at every level. They’re divided up into sub-categories purely out of self-defense and stock-management and guidance and teacher’s headaches and parent’s bewilderment. Possibly the kids find it useful, too. The marketing stuff is a by-product, though possibly an overwhelming one at times. And of course as the Young pushes into Adult, the lines blur, and there’s leakage, but it’s not really a problem, if anything it’s an advantage.

I take grave, grave issue with that checklist as a working definition of YA.

I can’t really account for cyncism and efforts to dumb down work. It’s not necessary. Kids aren’t dumb. They’re just growing. People should remember that.

Not as a phrase – as a concept.

Put it another way – you’re quite happy calling what you write children’s fiction. Why does that change once we cross the threshold of 13 years old?

Yes! An accord!

It changes again when you cross the threshold of 20, or 21 or somewhere around there. Anybody hear tell of this new marketing category, “New Adult”?

Apparently that is now a thing.

Oh, and even though I’d read Asimov and a bit of Heinlein and Banks and a few others, it wasn’t until I read Stand On Zanzibar and The Sheep Look Up that I finally felt I had discovered science fiction.

When people talk about writing aimed at kids, this is what they mean, or should mean. You do not write as if the kids are dumb. You write as if the kids are growing.

Um. That is not my circus. Those are not my monkeys.

fuck’s sake……..

Late stage Capitalism. What are you gonna do?

(Sorry if I’m starting to fill up the comments section haphazardly.)

It doesn’t, really, it’s still children’s fiction – YA is just a sub-category of that. If it wasn’t YA written over the shelves, it’d be 13-18. In libraries it’s often both. I’ve even heard professionals – agents, editors, booksellers – divide them further into Younger and Older Teens, though I haven’t seen it on the shelves. YA is a purely practical thing – in my mind and in the minds of most of the people I know. Yes, marketers take tedious advantage of it, but what isn’t tedious about marketing taking advantage of things?

A useful phrase for these categories is that they are arbitrary – in that of course no two 13-year-olds develop at the same speed – but not random, inasmuch as it is useful and necessary to have the cut-off point somewhere as a point of reference.

To be honest, what really kicks my ass about the whole YA thing is the young protagonist requirement. Because yeah, sure, anyone under the age of 18 is *simply mentally incapable* of identifying with anyone older than they are, right? Especially if they’re like, *really* old, you know, like *forty* or something…..

That’s the infantilisation process at work, right there.

I agree with you about the young protagonist thing. Having them is great, but it shouldn’t be a requirement, and suggesting that young readers can’t identify with adults is tantamount to suggesting you can’t identify with anyone different from you which would be a disastrous approach to take to writing or reading. Some writers get around it by having the protagonists age over the course of a series. Rowling did it, but Philip Reeves had his leads age, marry have a child, grow old and die over the course of his Mortal Engines series. I mean, I don’t think the authors wrote them as a get-around but it rather proves how asinine a restriction it is.

To be fair I also don’t know whether it HAS become immovable fixed received wisdom, or if putting young protagonists in children’s books is just something modern authors naturally do. At this point, though, I suspect if you wanted an adult protagonists you’d need to be established and you’d have to push for it. How hard you’d have to push, I don’t know. It might suddenly seem quote innovative. I don’t think writers are banging down the doors for it, though. Margo Langan’s Tender Morsels and Brides Of Rollrock Island had adult protagonists.

Peter Watts,

Really? It’d be kinda interesting to see what your take on it is. I feel like John Brunner has been abandoned by mainstream sf for some ungodly reason and it actually makes me almost as sad as the fact that George Allec Effinger died before he could finish the Marid Audran series

Peter,

If you haven’t heard of it yet, try the Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality fanfic. Puts an interesting twist on HP by making both the protagonist and the antagonist smart. The writing is sometimes (especially at the begining) a bit rough but I enjoyed it a lot. Good fun.

Hey, is this where we come to chest thump about what *we* read when we were kids? Awesome.

Growing up in the 70s/80s by my early teens (11-13) it would have been Clarke, Asimov, Heinlein, Bradbury, Jules Verne, HG Wells, Frank Herbert (Dune also a YA novel by that panel’s criteria, BTW), Richard Matheson, fantasy landmarks like Tolkien and TH White, pulp like Lovecraft, Robert E Howard, Moorcock and Doc Savage adventure novels from the 40s. I also had a taste for more lurid fare like spy novels by Ian Flemming, Robert Ludlum, and Leslie Charteris, sprawling historical soap operas by James Clavell (no explanation for this), and a rather appalling habit of reading major movie novelizations, both before and after having seen the movie (video rental stores were not quite a thing yet, ok?).

I guess that’s what you get when you let a kid run wild in a library, without trying to make them into a demographic. Thing is, I’m pretty sure *most* of the stuff on that list, even the big names in science fiction who have gained a lot more respectability with time would have been considered “Young Adult fare” by *serious* readers back then, when anything that smacked of the fantastic was considered adolescent. Young Adult and snobbish contempt for it has always been a thing, even if what constitutes YA is always changing. Those of us who emerged from the womb reading hard science fiction can take a pass I suppose, but the rest of us may need to look more closely at how different modern YA really is from some of the stuff we read when we were younger, and how much comes down to superficial differences and nostalgia.

I do agree with some previous comments, that just about the last thing I was interested in was stories featuring young leads. To me that *was* kid’s stuff. My family’s multiple attempts to inflict CS Lewis on me were met with disdain. This may simply be a generational thing. There wasn’t quite the abundance of entertainment media produced specifically for rigid youth demographics yet, so we mostly just consumed what people of any age with imagination consumed. Stories featuring kids typically (but not always) lacked the sophistication of stories featuring younger leads do today. Today *everything* feels like “Young Adult” to me, from primetime television to every movie at the multiplex, because nobody wants to see disgusting middle age people like me featured prominently in their fiction anymore. Who can blame them. Ew.

.

Our Gracious Host wrote: I have to wonder if YA does that, if it improves one’s reading skills or merely panders to them. I doubt that your vocabulary is any bigger when you finish Harry Potter and the Well-Deserved Bitch-Slap than when you started. You may have been entertained, but you were not upgraded.

Au Contraire, Dr Watts! When I and my friends read A Clockwork Orange at an average age of about 15 years, we thought it was incredibly awesome because it provided us with a new slang that was unlikely to be understood by anyone else in our shiny new suburbs. Not long after reading the book, we were all using Nadsat as much as possible and we found ways to intrude it into almost any conversation we were having, regardless with whom or regarding what. Interestingly, years later, at the peak of the Cold War, some adult kids of early defectors came within my peer group, and when they started talking amongst themselves in Russian, I was actually shocked to discover that I understood much of it.

Thus, A Clockwork Orange is not merely YA, but very educational YA. Yet, reading it from the age-group of the protagonist, it might be all too easy to fall into the mindset of the protagonist. It’s arguable as to whether Little Alex (and his droogs) are the products of their failed socialist utopia, or whether they’re simply the product of a developmental stage when nearly adult intelligence and adult drives are little moderated by scant adult conscience. In the end, Little Alex may “win”, but for how long? If he lives long enough, his dreams may provide his own internal “Ludovico” aversion therapy. The story doesn’t suggest this, and one might say that this definitively keeps this in the YA category. That might be one of the unspoken rules for the subgenre.

To the other thing: writing simply — yet thought-provokingly — for the YA-and-younger audiences, that’s hard. As adults writing for adults, we are all too easily drawn into seeking to display subtlety and stylistic flourish, and in many cases (as adult readers) we are willing to forgive a lack of clarity of story if presented with enough literary legerdemain. Yet some writers do manage to pull off the real trick, which is to tell a story at multiple levels, which makes sense on all of those levels. Early works by Ursula K LeGuin are good examples, especially the early Hainish Cycle titles such as Rocannon’s World. It seems like a lot of hobbitry but there’s a fair amount of science snuck in there.

Borderline-sitting in the fuzzy domains between fantasy and SF in the Fifties and Sixties, Zenna Henderson’s “People” cycle mixes the very straightforward and seemingly simple short stories with the fairly complex bridge pieces written to try to make a novel out of the reprinted shorts. Yet if we judge it by the rules-of-YA as laid out above, this cannot be YA because almost all of those short stories have a pretty clear vision of what is going on in the minds of tweens and young-adults (even super-powered ones!), but the recurrent theme set out is of teachers with special talents for reaching the nascent adult in the troubled teens portrayed, and the world is less corrupt than it is ignorant or superstitious. Yet as a teen I found these stories extremely readable, and reading them all again a few times throughout my adult life I have found them as readable, yet bringing new understanding on new levels. The prose is straightforward and so are the stories, yet for the first-time reader back in a simpler day when these ideas hadn’t been done to death in TV and film, the stories were full of surprise and wonder, and often full of a better way of looking at things. Does anyone even really try to do that anymore?

Missed this bit:

This is overly harsh. Although I’ll deny it in a dozen other arguments when Im busy looking down my nose at something someone else enjoys, even reading trash is better than no reading. Especially with speculative fiction. There’s a lot of visualization that goes on when reading, and sci fi/fantasy give our internal rendering engines a good work out when imagery isn’t spoonfed into our brains like in a movie, instead relying on our own minds to conjure images from text. Imagination and the ability to visualize complicated, vague or abstract concepts are highly useful skills in almost any field.

You’d also be surprised about the vocabulary, I think If most people could speak at least as articulately as the typical passage in a Harry Potter book, they’d find a lot of things in life much easier. But so many people, in my own Country at least, increasingly can’t string together a few words with any confidence or sounding like a dumbass to people with command of language. So even Harry Potter can develop skill and confidence in processing language, and parents always hope that confidence encourages them to move on to more challenging things.

I’m amazed, in retrospect, of how much vocabulary I picked up just from reading comic books as a kid with their ridiculous dialogue that nevertheless featured words and concepts that I was unfamiliar with. “Begone foul miscreant, or I shall use the ultimate nullifier to shrink you into the subatomic multiverse! Have at Thee!” Between faux Shakespearean comics dialogue, and all the dated idioms I was picking up from reading pulp novels from the 40s and 50s, I had a *really* weird vocabulary as a kid, that would sometimes leave my friends baffled. Their vocabularies consisted

mostly of new and creative use of vulgarities. It really is a wonder I didn’t get punched more.

In an age where kids have so much more competition for their attention, any reading is good reading as far as I’m concerned. Many of us here are recounting experiences from before the age of basic cable, let alone video games. I’m under no illusion that I would have been the same reader had

goddamn Super Nintendo hit when I was in my early teens. Luckily, I was blessed with awful Atari games, and if those things could hold your attention for more than 20 minutes at a time, you were probably never going to be much of a reader anyway. If it takes some scientifically formulated accessibility torpedo keyed to a specific age range to get a kid reading these days, so be it.

.

“I’m puzzled by the idea that “corrupt/dystopian society” should be a defining characteristic of YA.

AngusM

You need the ‘rebellious young folks fight an oppressive society’ trope if you really want to lucratively tap into the mindset of a resentful teenager who’s just been told to take the bins out. This is the key not so much to YA fiction, but to successful YA fiction, particularly the kind that spawns movie franchises, especially if said rebellious young folks are also ubermenschoid mutants the corrupt society, or some other buncha old people, want to kill just coz they’re different. And, y’know, better than everyone else, not that YOU care. Stay out of my room!

I blame John Wyndham. Which reference gives you an idea just how freakin’ old I am.

Yes, this. I graduated from kid’s books (mostly Doctor Who tie-ins and Biggles) to adult fare (mostly Ian Fleming, Leslie Charteris, Alistair Maclean & Desmond Bagley) somewhere between the ages of about nine and eleven. The upshift in the demands the prose made was minimal, the learning curve for the content was, of course, somewhat steeper. But what was identical in both cases was that the protagonists of this stuff were all adults. It would never have occurred to me to want to read about people my age or a few years older. In fact, I recall that once, when I ran out of Biggles adventures, I borrowed a couple of a friend’s Famous Five books (they had similarly colourful spines, I seem to remember, and were about the same size). I remember very clearly being totally dismayed to discover that the protagonists were kids, and I bailed out on the spot. Kids, by definition, were like me, and that rendered them pretty dull. Biggles and Who, by contrast, were grown men, with lived years of experience behind them (in the Doctor’s case, rather a lot of years!) and all the gravitas and fascination that implied. I was in a hurry to grow up and get out into the adult world, and these were aspirational signposts for me, pointing the way.

Love the exchanges going on in this comment section…

While I largely agree with Richard’s take on the direction modern culture is going, I’m not sure if calling it “late-stage capitalism” helps very much (as it brings a lot of baggage). But the general point seems correct. Nearly anywhere you go around the world, it seems cinema and books have changed over the past couple of generations, from tackling big “serious” issues, spirituality, poetry, Art (capital A), life and the soul, to largely being entertainment.

On the other hand, as the world has gotten richer, there’s a lot more literacy and people who have more time for cinema, books, etc., so I wonder how much of this is just a broadening of the cultural base.

Instead of record collections, people today can stream nearly any piece of music ever recorded, at any time. Classical music is much less followed today, but kids can tell you all about 20 different classifications of EDM. TV is incomparably richer and more varied (and more “grown up”) than what I grew up with in the 1970s and 80s. Tarkovsky and Kubrick have given way to Michael Bay … But Bong Joon Ho has been given $60 million to make a scifi film for Netflix.

(Only pro wrestling remains the same…)

Not sure if I really have a point, except I think for each thing we’ve lost, we’ve probably gained something else, and maybe we’re just too close to the changes to really see it. And the rise of adults reading YA is just a small piece of a much larger set of trends occurring across culture.

Andrej,

Puts an interesting twist on HP by making both the protagonist and the antagonist smart.

No, it doesn’t. It makes the protagonist immensely stupid, tries to make them seem smart by handing them the script, but still fails at that because the author doesn’t seem to get what makes for someone actually being smart. The description of Donald Trump is “a poor person’s idea of a rich person”, and that applies very much here. If someone who couldn’t make it through grade school dropped out, told them self they were always immensely smart despite not being able to hack it, and wrote a self insert with all the arrogance and hate but none of the ability, that pile of dreck is what you would get.

It also guts all the charm and deeper ideas that people enjoy from it in favor of a religious screed. It is Ayn Rand with even less skill or thought, and more racism and misogyny.

It appears I don’t have all the chest thumping out of my system yet, but I’ll try to put in perspective at the end. Someone above mentioned Poe, and I recall now that before I had even graduated (though some would quibble if this was really an upgrade, no doubt) to classic sci-fi in my early teens, I had read the collected works of Poe, Mark Twain, Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Aurthur Conan Doyle, HG Wells, Jules Verne, a reasonable amount of Dickens–goddamn Moby Dick–all by the time I was about 9 or 10. For leisure.

This strikes me as utterly remarkable now. That there was an age where I could just pick up a book, any book, and read it for leisure. I recall not struggling nearly so much with putting together antiquated dialect and dated language from context as I would now. This is something my child’s brain could do, that my adult one would struggle with.

This, however, is something I have to credit to the parental units. I read this stuff because it was what was around. My parents used to gift me handfuls of these paperbacks. They were all considered “young adult reading” . How crazy is that? How many of us could struggle through Moby Dick today for kicks, if not required to for school?

Now, perspective. I read them because we lived in a rural area, there were only three goddamn channels on the television, and they all sucked. I was lucky enough I guess, to be a product of my time and environment, and to develop a reading for leisure habit that I carried with me the rest of my life. I have no illusion that if I were born even ten years later, with the advent of basic cable and more sophisticated video games, that I would be the same. And the internet, that great swirling vortex of inanity that no free time can escape? Forget about it. I’d have been toast. That kids read at all today is remarkable to me.

Realizing that, I would not choose to let my niece detect any derision from me over any choice of reading material, even modern YA. No doubt I will have to look at the crushing disappointment in her eye when I gift to her some of the things I read when was young, in hilariously out of style dead tree volumes, and watch her wonder if I, in fact, hate her.

Yet the general reaction I get when I tell people in the US I read Science Fiction is that I am reading kids material. Funny that my two favorite authors are ranting about the infantilization of a target demographic by ad executives / publishing houses.

You are right, Peter. It is the same with pop music:

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/science-proves-pop-music-has-actually-gotten-worse-8173368/

Also, Nellie was satire?? You should have published it on the 1st of April.

(Told you I am not the sharpest pencil, Adam.)

A fellow Saint fan. At least by pre-teen library card tatstes. *High Five*.

It’s interesting this generational shift that seems to have happened, as to whether kids really are interested in seeing other children enjoy protagonist spotlight in their fiction. Judging by the rampant commercial success of Harry Potter, or The Hunger Games, or the Twilight series (the second two inspire prolonged fits of 1978 Body Snatcheresque point-screeching in me, so I’ve never actually read/watched them, and cannot speak intelligently on their merits), the tide seems to have turned on that. Although, one can never really separate their actual appeal to youth, and their success due to the current generation of pop-culture worshiping 20 and thirty somethings.

For my part, and I can only speak as a former young boy (my sister seemed content chewing through Nancy Drew mysteries…but then, that was what was *given* to her to read–an entirely different can of worms), but stories that featured young adult leads were kids stuff to me. I resented them. There was something that didn’t ring true about them, something that was talking down to me, and I looked to adult fiction to give me more credible accounts of people engaging in exceptional deeds. I don’t know if it was aspirational in nature, or simply that it hampered my suspension of disbelief when children were shown pulling off adult feats. I was, after all, keenly aware of all the limitations of my own abilities, and my own life. In contrast, the lives of adults seemed so much more exotic and plausible for the sort of high adventure and fantastic scenarios I enjoyed.

It’s telling that my generation favors Han Solo over Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars pantheon. Luke was the ostensible lead –the embodiment of the Campbellian Monomyth. But godlike power fantasy aside, he was also the annoying kid who wanted to go to Toshi Station to pick up some power converters, while Han was the guy who shows up in his sweet ride, shoots first, bangs your sister, probably lets you finish his beer, then takes off before the end because the rest of you are really a drag. There’s really no contest, and this was a conclusion I reached at a very young age. Let us not speak of the Prequel featuring a primary school child flying attack fighters and saving the day. Despite Lucas’s contention that the Star Wars movies were always made for children, this is something I absolutely would have rejected as a child. As a child, my heroes were not other children. Ever.

When did that change? Has it changed? On the one hand, stories featuring youth leads are more sophisticated now than they used to be. Peter pointed out the darker tones and subtext in the latter chapter of the Harry Potter books. Compared with a lot of the stuff deliberately aimed at young adult readers when I was a kid, this is a marked change. Perhaps it would have won me over had I benefited from that shift in my youth. On the other hand you see that the more sophisticated nature of these stories are bringing in adult readers as well, blurring the lines between “youth fiction”, and simply “fiction”, albeit that which isnt writing up to their potential as adult thinkers–which I suppose is the main thrust of Dr. Watts’s latest rant.

Im still not convinced that placed side by side, a child wouldn’t choose a book that featured more “adult” situations and subject matter, simply because the alternative featured a younger protagonist. Children are every bit as bloodthirsty, if not more so, than adults, and every bit as enchanted by lurid subject matter. They are also keenly aware of when they’re being excluded from the party. As adults, we construct these separations for our own comfort, rather than theirs.

.

This may have much to do with “Individuation” as Jung would have it. I first encountered the term in the context of an infant realizing that it is independent of the mother and that other things in the universe are also individuated. This relates a bit, developmentally, to Theory of Mind, at that stage. Yet this whole “we are ourselves and we are not others” bit continues through development and in some ways it’s a bit more subtle and in other ways it’s not very subtle at all. Relevant to your question, up to a certain point, children are very solidly identified with and identified to their parents and/or teachers they find acceptable. Yet as they grow older, they develop their own peer groups and associations and especially in the teen and “YA” years their peer group individuates from adult society. The age range from roughly 15-25 or so is spent trying to dissociate from the parent generation. At times the avoidance of adults is fairly generalized and at times it’s more tuned to specific people or their

character traits or opinions they’ve expressed. Coming from one teen it’s one thing, but if you get several teens/YA to have the same reaction against someone or something, it becomes somewhat normative. Thus, create a sufficiently objectionable character in a sufficiently popular YA novel and you’ve just normalized a specific disdain into a large number of the upcoming generation.

Honestly, even in our 50s, those of us who saw Star Wars (IV) in our late teens/early 20s have spent most of our lives trying rather desperately at times to not be Darth Vader or Grand Moff Tarkin. “Abandon ship, in our moment of triumph? I think not!” Did whoever wrote that line, write into our generation a serious degree of caution that doesn’t ever think we’ve won until we’re damn certain of it?

Of course, this same phenomenon, of aligning to an age-peer group while becoming almost antithetically opposed to elders beyond a certain age and/or of certain outlooks, explains the requirement to have a young protagonist. Anything else would be almost summarily rejected by most off the target audience.

They tried that with me, and the jury’s still out on how well that turned out. The good side of it is that there’s no question that I’m literate, but then again, there was no question that I was literate when I was in second or third grade. Yet the general opinion, insofar as I have been able to get at it, is that having sopped up so much wordage without necessarily being firmly grounded in the disciplines behind the words, allowed me to be over-estimated by people trying to do placement assessments, meaning that I was skimped on the basics in many ways. In many subjects, it is possible to speak well in those subjects without being deeply grounded in them. Perhaps this is especially the case in those of us who glossed over the unfamiliar or difficult parts, letting context fill in the blanks sufficiently so as to move on to the next bit of story. I was into my early twenties before I really understood this, and started to take pains to check the dictionary, encyclopedia, any experts I could find, to try to fill in the blanks. It may be valuable indeed to have YA-level works available so that kids have no choice but to read adults works, and incorrectly fill-in-the-blanks with miscomprehended guesswork.

If anyone has the time, patience, and energy to write a YA about some bewildered adult discovering that they’d have been a lot better informed and a more precise thinker if only they’d read more YA, and then they read that YA and their mental faculties all start falling into place, because it’s never to late to have your second childhood… I will leave this to the reader as an exercise to determine whether or not I am taking the piss. In any case, it may have been nearly done as such, already, and done well. Consider whether or not Stephenson’s The Diamond Age ought perhaps to be thought of as YA, or perhaps as what YA ought to want to be.

@ScottC: You and I read about the same stuff in about the same timeframes, I think. However, I was able to read the “Perelandra” CS Lewis but didn’t at all “get it” because of the heavy religious influence… I pretty much glossed over that. Yet in later years, when pondering anything remotely theological, I find myself deeply informed by those first experiences with that sort of thought. Somehow I never could stomach all of that “Narnia” stuff.

Folks, where do we categorize John Christopher’s “Tripods” books, which were pretty clearly aimed at the 12-15 age group? Or the likes of Howard’s “Conan” books, HP Lovecraft, or L. Sprague DeCamp? My same friends who read A Clockwork Orange also were passing around copies of the Conan books, Lovecraft was definitely all the rage in the teen literati crew, boys’ division. A taste for sword-and-sorcery leads perhaps inevitably to Fritz Leiber by way of “Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser”. These latter generally wouldn’t fit the list, above, of what’s YA. But would Kipling’s “Just So Stories”, specifically the “Jungle Book” tales about Mowgli? Hint: Shere Khan is the Mean Old Man.

Godfuckingdamn. So many comments to get caught up on.

Look, forget education, age, and whether or not kids today are dumber/worse educated or whatever. When you write with a certain complexity you cut off perhaps half of a potential market. And maybe those “mindless” folks are the ones who make viral marketing work. Getting those people via EQ as opposed to IQ seems to be part of the whole sparkly vamp success.

To me, it’s that complexity that makes Watts Watts. But also that weird-ass thing where he takes geometry or biology or alienscapes and makes it poetic.