Dolphinese

This is how you communicate with a fellow intelligence:

you hurt it, and keep on hurting it, until you can

distinguish the speech from the screams.

—Blindsight

Believe it or not, the above quote was inspired by some real-world research on language and dolphins.

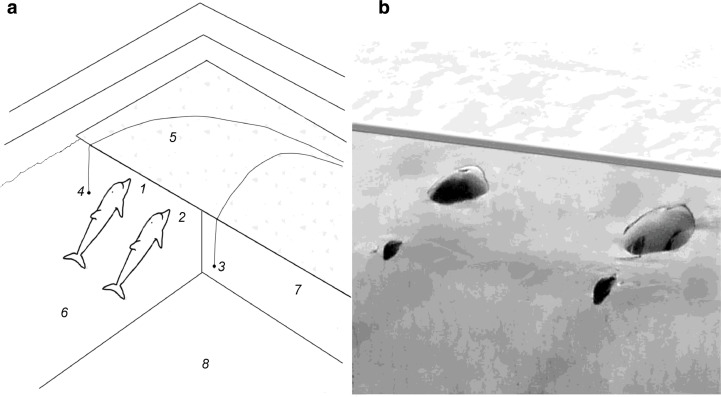

Admittedly the real-life inspiration was somewhat less grotesque: scientists taught a couple of dolphins how to respond to a certain stimulus (if you see a red circle, push the yellow button with your nose— that sort of thing) then put them in different tanks but still let them talk to each other. Show the stimulus to one, but put the response panel in the tank with the other. Let them talk. If the dolphin in the response tank goes and pushes the correct button, you can conclude that the two of them communicated that information vocally: you can infer the presence of language. What’s more, you’ve recorded the vocalizations that carried that information, so you’ve made a start at understanding said language.

As I recall, the scientists rewarded correct responses with fish snacks. Blindsight‘s scientists didn’t know how to reward their captive aliens— they didn’t even know what the damn things ate— so they used a stick instead of a carrot, zapped the scramblers with painful microwaves for incorrect responses. It was more dramatic, and more in keeping with the angsty nihilism of the overall story. But the principle was the same: ask one being the question, let the other being answer it, analyze the information they exchanged to let them do that.

I’ve forgotten whether those dolphins ever passed the talk test. I’m guessing they did— a failed experiment would hardly make the cut for a show about The Incredible Smartness of Dolphins— but then, wouldn’t we have made more progress by now? Wouldn’t we at least know the dolphin words for “red circle” and “yellow button” and (given that we are talking about dolphins) “casual indiscriminate sex”? Why is it that— while dolphins seem able to learn a fair number of our words— we’ve so far failed to learn a single one of theirs?

I was always a sucker for the dolphins-as-fellow-sapients shtick. It’s what got me into marine mammalogy in the first place. One of my very first stories— written way back in high school— concerned a scientist living in an increasingly fundamentalist society, fighting funding cuts and social hostility over his attempts to crack the dolphin language because the very concept of a nonhuman intelligence was considered sacrilegious. (In the end he does get shut down, his quest to talk to the dolphins a complete failure— but the last scene shows his dolphins in a tank quietly conversing in their own language. They’ve decided to keep their smarts to themselves, you see. They know when they’re ahead.)

Anyway. I watched all those Nova documentaries, devoured all the neurological arguments for dolphin intelligence (Tursiops brains are 20% larger than ours! Their neocortices are more intricately folded, have greater surface area!). I read John Lilly’s books, embraced his claims that dolphins had a “digital language”, followed his Navy-funded experiments in which people sloshed around immersed to the waist in special human-dolphin habitats.

By the time I started my M.Sc. (on harbor porpoises— one of the bottlenosed dolphin’s stupider cousins), I’d grown significantly more skeptical. Decades of research had failed to yield any breakthroughs. Lilly had gone completely off the rails, seemed to be spending all his time dropping acid in isolation tanks and claiming that aliens from “Galactic Coincidence Control” were throwing car accidents at him. Even science fiction was cooling to the idea; those few books still featuring sapient dolphins (Foster’s Cachalot, Brin’s Uplift series) presented them as artificially enhanced, not the natural-born geniuses we’d once assumed.

We still knew cetaceans were damn smart, make no mistake. Certain killer whale foraging strategies are acts of tactical genius; dolphins successfully grasp the rudiments of language when taught. Then again, so do sea lions— and the fact that you can be taught to use a tool in captivity does not mean that your species has already invented that tool on their own. The expanded area of the dolphin neocortex didn’t look quite so superhuman when you factored in the fact that neuron density was lower than in us talking apes.

So I passed through grad school disabused of the notion that dolphins were our intellectual siblings in the sea. They were smart, but not that smart. They could learn language, but they didn’t have one. And while I continued to believe that we smug bastards routinely underestimate the cognitive capacities of other species, I grudgingly accepted that we were still probably the smartest game in town. It was a drag— especially considering how goddamned stupid we seem to be most of the time— but that was where the data pointed. (I even wrote another story about cetacean language— better-informed, and a lot more cynical— in which we ultimately did figure out the language of killer whales, only to discover that they were complete assholes who based their society on child slavery, and were only too willing to sell their kids to the Vancouver Aquarium if the price was right.)

*

But now. Now, Vyacheslav Ryabov —in the St. Petersburg Polytechnical University Journal: Physics and Mathematics— claims that dolphins have a language after all. He says they speak in sentences of up to five words, maybe more. The popsci press was all over it, and why not? I can’t be the only one who’s been waiting decades for this.

Now that it’s happened, I don’t quite believe it.

It wasn’t a controlled experiment, for one thing. No trained dolphins responding to signals that mean “ball” or “big” or “green”. Ryabov just eavesdropped on a couple of untrained dolphins— “Yana” and “Yasha”— as they chatted in a cement tank. We’re told these dolphins have lived in this tank for twenty years, and have “normal hearing”. We’re not told what “normal” is or how it’s measured, but concrete is an acoustic reflector; it’s fair to wonder how “normal” conditions really are when you take creatures whose primary sensory modality is sound, and lock them in an echo chamber for two decades.

Leaving that aside, Ryabov recorded Yana and Yasha exchanging 50 unique “noncoherent pulses” in “packs” of up to five pulses each. Each dolphin listened to the other without interruption, waiting until the other had finished speaking before responding in turn. Based on this Ryabov concludes that “most likely, each pulse … is a word of the dolphin’s spoken language, and a pulse pack is a sentence.” He goes on to compare these dolphin “words” with their human equivalents. (Dolphins words are much shorter than human words, for one thing— only about 0.25msec— because their wider frequency range means that all the phonemes in a “word” can be stacked on top of each other and pronounced simultaneously. Every word, no matter how long, can be spoken in the time it takes to pronounce a single syllable. Cool.)

I find this plausible. I do not find it remotely compelling. For one thing, it doesn’t pass the “tortured scrambler” test: while the pulses are structured, there’s no way of knowing what actual information— if any— is being conveyed. If Yana consistently did something whenever Yasha emitted a specific pulse sequence— say, swam to the bottom of the tank and nosed the drain— you could reasonably infer that the sequence provoked the behavior, that it was a request of some kind: Dude, do me a favor and go poke that grill. Language. But all we have here is two creatures taking turns making noises at each other, and dolphins are hardly the only creatures to do that. If you don’t believe me, head on over to Youtube and check out the talking cats.

Nobody denies that dolphins communicate. Lots of species do. Nature is full of animals who identify themselves with signature whistles, emit alarm calls that distinguish between different kinds of predator, use specific sounds to point out food sources or solicit sex. Killer whale pods have their own unique dialects. Honeybees communicate precise information about the distance, bearing, and quality of food sources by waggling their asses at each other. The world is rife with the exchange of information; but that’s not grammar, or syntax. It’s not language. The mere existence of structured pulses doesn’t suggest what Ryabov says it does.

He does buttress his point by invoke various cool things that dolphins can do: they can learn grammar if they have to, they can recognize images on TV screens (responding to a televised image of a trainer’s hand-signal the same way they would if the trainer was there in the flesh, for example). But all his examples are cadged from other studies; there’s nothing in Ryabov’s results to suggest a structured language as we understand the term, nothing to “indirectly confirm the hypothesis that each NP in the natural spoken language of the dolphin is a word with a specific meaning”, as he puts it.

It’s a tempting interpretation, I admit. This turn-by-turn exchange of sounds certainly seems like a conversation. You could even argue that a lack of correlated behaviors— the fact that Yana never did nose the drain, that neither pressed any buttons or got any fish— suggests that if they were talking, they were talking about something that wasn’t in their immediate environment. Maybe they were talking in abstracts. You can’t prove they weren’t.

Then again, you can say all that about Youtube’s talking cats, too.

So for now at least, I have to turn my back on the claim that my life-long adolescent dream—the belief that actually shaped my career— has finally been vindicated. Maybe Ryabov’s onto something; but maybe isn’t good enough. It’s a sad corollary to the very principle of empiricism: The more you want something to be true, the less you can afford to believe it is.

But all is not lost. Take long-finned pilot whales, for example. They were never on anyone’s short list for Humanity’s Intellectual Equals— the Navy loved them for mine-sweeping, but they never got anywhere near the love that bottlenosed dolphins and killer whales soaked up— and yet, just a couple of years ago, we learned that their neocortices contain nearly twice as many neurons as ours do.

Maybe we’ve just been looking at the wrong species.

I just saw a news article that purports that whales also communicate by slapping the water with fins and breaching. Whales talk to each other by slapping out messages on water in case you want to check in to another intelligence thing.

uh, holy crap, stuck for 20 years in an echo chamber. I’d think they’d be insane by now. I wonder if dolphins have the same problems that humans have when their voice is reflected back to them after a very short delay. It causes us to shut up. (hence people building a shut-up directional speaker. can we use that in presidential debates?).

also, speaking of pinnepeds, have you looked in to walrus intelligence? I’ve read pretty cool things about them.

So long-finned pilot whales are the Kaiser Soze’s of marine mammals, it appears, hiding in plain sight.

I notice that wiki list didn’t include raccoons, which probably means they’re even smarter than long-finned pilot whales.

I once asked a philosophy prof who rejected my assertion that dolphins were probably as smart or smarter than humans (after reading Lilly, I believe) why he thought they weren’t. His, “Because we study them, they don’t study us,” response kind of stuck with me, and I agree that being able to bootstrap our intelligence with tools to build reference libraries and the material to fill them does seem to allow us to be smarter in many ways, especially in terms of controlling our environment, but something Lilly wrote about dolphins being able to “see” things such as the lunch you just ate because they use sonar (I’ve never tried to verify this claim) and so have a different world view made me wonder if we don’t understand their language because they just don’t give a shit about the same stuff we do, and we’re not able to grasp what they do care about. So, the problem of testing may result from a lack of shared meaning? The test for scrambler intelligence might well go some way to circumventing this problem (until PETA and like-minded pinkos put a stop to it), as pain seems to be a universally shared experience, but it might also just be possible that they’re masochists, or sufficiently enlightened to be able to rise above the pain.

Ah, dolphin intelligence, and presumably language. Probably every aspiring writer who’s even dabbled in SF has had a go at the topic, I’m no exception although my “expertise” is more in data networking rather than in marine mammals, as is your actual expertise.

You, at least, have had a lifetime of training in resisting confirmation bias. And perhaps we are looking at the wrong species! I seem to recall that in Blindsight, the Scramblers might not have been exactly self-aware in the way that humans (and arguably chimps, elephants, dolphins etc) are, but they were able to use language. We humans are pretty well specialized for and by the use of language; it’s the real hallmark of our species to use a particular type of language, which has things like verbs, nouns, articles in most languages, case and declension in most languages. Yet I think we all have pondered the possibility that perhaps a lot of humans can speak just fine but are otherwise barely to be considered intelligent even by chimp standards. My point is that we may be overly linking the notions of language and intelligence. Perhaps that’s a confirmation-bias that’s effectively built in, for us. Does intelligence really need language? Perhaps a good argument can be made that “broad” intelligence needs or at least very much benefits from language, but some kinds of intelligence might only be slowed-down into ineffectiveness by abstracting them to symbologies. Cats are absolutely brilliant when it comes to the logic of getting a mouse’s head into their mouths, but even if they could articulate it, mightn’t they suddenly become incompetent if they tried to talk about it as they did it?

Of course, argument by whimsical analogy isn’t really useful… but we should perhaps consider how the FOXP2 gene was discovered, by looking at the case of the “KE Family”. They had developmental verbal dyspraxia caused by a defective FOXP2 gene, causing motor problems. We presume that without the modern FOXP2 gene in non-damaged form, we wouldn’t have the motor capacity to speak; with FOXP2 in the modern undamaged form, we might have the motor control but perhaps not the hardware to control. I don’t know of any research which has analyzed, for example, the “defects” of throat and soft-palate which enable us to speak but also put us at risk of choking in a way that is unheard of in the rest of the apes… but could we have spoken well without these conserved minor mutations, even if we had the ability to control unmodified “parts”? Note that the KE family’s problems aren’t merely of motor control but also include some cognitive types of difficulties. Yet their version of FOXP2 is damaged from a functional one, we don’t know entirely how that differs from whatever was circulating in humans before the modern version became widespread. Perhaps dolphins are in a comparable position; they are awaiting a serendipitous mutation that will give them the ability to both control and “syntactify” the output of their exceptional sound-creating apparatus.

Mr Non-Entity,

What about Chomsky’s hypothesis that language was evolved in order to allow individuals to speak to themselves – that it was necessary for the inner monologue that accompanies and promotes consciousness? The corollary of this is that language really is necessary for intelligence, at least human-like intelligence. For other types, it’s not so obvious, of course.

@Lars: Chomsky might be close to correct, but in a very general sort of way. Most of us do have that internal monologue, often to the point where we wish the damned thing would shut up for a while. Yet apparently those people who have been profoundly deaf since birth have an equivalent form of introspection, but it’s visual, or not even visual so much as it’s a sort of holistic experiential sort of thing. See also the memoirs of Helen Keller, or for that matter, this sub-reddit discussion. So I would conclude that Chomsky is not entirely correct or that there are at least some exceptions to that case. Otherwise if we took him too seriously we might think that deaf people can’t have human intelligence, which actually was a widely-held belief back in the Roman Era, etc.

Chomsky’s theories fit, I think, into the same line of reasoning as gave us the notion of Jaynes’s Bicameral Mind theory. Some light might be shed, including some other context being brought in, in this book review (What Kind of Creatures Are We?Chomsky, Noam, 2013, reviewed by Persky, Stan).

Personally, I think that language as we humans have it, may be one of the greatest imaginable flukes of luck in the history of the universe. Here’s one of our predecessor species walking around almost ready to have language, and then “poof” as if by magic now there’s a fully formed third-of-three gene which seems to jump us all of the way up from pointing and grunting, to articulate speech including temporal binding and contextual variances that add redundancy to the basic symbolism. Out of nowhere, case, declension, and a global explosion in fine arts and precision handiwork. Having the same thing happen also to other species (in other genera) on the same planet, beyond what one could believe possible from mere luck.

I always found Brin’s whimsical assertion that dolphins’ natural form of communication was something resembling haiku to be completely enchanting. I can’t trust any study that doesn’t account for the possibility that they might be speaking in verse.

By the way, a criticism of this ‘Crawl entry. The correct title was clearly supposed to be, “I Think I’m Speaking Dolphinese, I Really Think So”.

“I’ve forgotten whether those dolphins ever passed the talk test. I’m guessing they did— a failed experiment would hardly make the cut for a show about The Incredible Smartness of Dolphins— but then, wouldn’t we have made more progress by now? Wouldn’t we at least know the dolphin words for “red circle” and “yellow button” and (given that we are talking about dolphins) “casual indiscriminate sex”? Why is it that— while dolphins seem able to learn a fair number of our words— we’ve so far failed to learn a single one of theirs?”

Maybe we do know some dolphin words, but they’re all in different dolphin languages.

I mean, there’s no reason to assume dolphins all share the same language any more than there’s reason to believe humans do.

“Oh, sure, of course,” you might say. “But what I mean is, shouldn’t we know what the word for ‘red circle’ is for at least THOSE two dolphins?”

… but that assumes that they keep the same language. I mean, for us, language, once learned, is more or less stable between two participants. Sure, we might mutate words over time and could, on a whim, a friend might decide to start calling it ‘pasghetti’ instead of ‘spaghetti’ and keep it up that way until the joke gets old (little tip: almost immediately). But we only have humans for comparison. For all we know, we’re the exception, and for dolphins, coming up with new languages on the fly is the norm, a way to keep track of the in-group and the outsiders (“If you were one of us, you’d keep track with our words for things! Click-click-clack is SO last year’s word for fish, now we call it Clack-trill-click!”, or that a long term stable language never became essential and so each conversation, after a certain amount of time, starts with “let’s establish our terms for this stuff we’re going to be talking about, this thing I’m pointing at now, that’s a Click-Click,” even if Click-Click was “shark” last week, an this week it’s “tasty fish”, really it just means “Subject A.”

Just some random off-the-top-of-my-head thoughts that are probably way off base because I am not a scientist.

Let’s not knock pointing, though. It’s a pretty useful trick, and at my last check the only other animals on earth besides humans to intuitively understand it, are dogs and elephants. Even the higher apes struggle with the concept.

.

Mr Non-Entity,

A good critique. I was throwing Chomsky out here to see what the more qualified or thoughtful might make of his idea, and this is the sort of thing I was looking for – thanks.

Peter D,

I think that idiolects are actually fairly common within families, and they do tend to evolve through time. This is likely to be accentuated when families mainly interact within themselves and don’t have to communicate a great deal with outsiders. So this might not be a bad model for dolphin languages, particularly when you remember there is no possibility of a written form to counter change.

Surprised Ensign Darwin of SeaQuest DSV/2032 fame didn’t get a mention. Or am I? IIRC, he was annoying as hell.

Am reminded of the Dexter’s lab episode where he gives the dog the “gift” of speech giving voice to the species’ a.d.d. and ability to be easily entertained.

PS: A French plug for Beyond the Abyss:

Original

English v Goog translate

Deseret,

Er, “…Rift.”

Alexander Jablokov’s 1992 novel A Deeper Sea featured a breakthrough in communication with cetaceans by Russian researchers who tortured dolphins with auditory illusions until they started talking in order to make the confusion and pain stop.

It also had the wonderful element of dolphins being both genuinely intelligent and — it turned out — complete assholes. (All those stories about dolphins saving drowning humans throughout history? Something the dolphins did only when other humans could see them. If there was an isolated human with no one else around, they’d happily kill him or her. They were very contemptuous of humans, reserving envy only for the fact that humans had hands, which made masturbation possible. The dolphins tended to think it was really unfair that humans could do this and they couldn’t.)

Silly question: Have sonar signals been analyzed as part of dolphin language, or separate from it? Because, if you exclude sonar talk, some women I know don’t have a language, either.

Human communication is based on the massive overuse of words. We basically talk bullshit all day (e.g. debate the eloquence of wannabe fish). We create a lot of white noise, and gain information from the echoes. Just like dolphins.

But this noise isn’t that white at all. It conveys mostly social information: About the location, movement, relationships of others within society. Dolphins don’t need abstract words for it, because they are such words – they have their society swimming all around them.

Their environment, culture and behavior don’t vary much, which means, they need less words to get organized, because they already are. If everybody knows what to do when a shark pops up, the word “Shark!” is all you need.

You can be highly intelligent without the need for many abstract words – if all the information is either plainly visible, or already in your brain, ready to be analyzed.

You’ve probably heard of the aquatic ape hypothesis: Our ancestors really tried to become seals, but then changed their minds. It’s quite well-founded, and the only scientific argument against it seems to be: “Nah. It’s not sound science, coz we don’t like it” (scientists generally can’t handle well concepts as alien to science as reality). Well, at least it would explain, why we prefer to spend our holidays on beaches, rather than sitting on sparse trees in the African savanna.

Judging from human behavior, and dolphin behavior, you can assume a period of symbiotic co-evolution. We are instinctively attracted to each other, because we are kin spirits. Which means, we’ve co-existed and cooperated long enough to develop in-born instincts that complement each other.

Well. Science believes in magic, I don’t. Which makes my ideas about the world non-scientific and esoteric, I guess.

Peter Erwin,

That’s such a fantastic novel. Jablokov’s an interesting writer but he’s never quite matched that since (although his first novel, Carve the Sky, is also terrific).

I’ve never read the novel, but YouTube has plenty of videos putting the lie to that assertion. Dolphins come up with plenty of creative methods for sexual self-amusement. There’s a well known one of a dolphin using a dead fish towards those ends, but I’ll leave it to you to find it for yourself if you were inclined to do so.

I’ve often wondered if the dolphins don’t communicate by broadcasting pictures with their sonar. It might not be “photo quality” sonar, but something more like a sketch or caricature. In this case the dolphin doesn’t say, “Push the red button,” but draws a picture, with sound, of the other dolphin pushing the red button (or more probably, the button on the left.)

And how would someone prove this? Does a dolphin encode sound in any fashion we’d understand?

Incidentally, one of the alien races in James Cambias’ “A Darkling Sea” has this as one method of communication (humans wind up having to decode a secondary communication channel done via tapping).

I’ve long thought that “language” might be a bad metric of smarts for those guys on exactly that basis; there’s much less impetus to develop abstract symbols for things when you can simply communicate a picture made out of sound. Likewise, many questions (“How do you feel?” “Are you hungry?” become redundant when you can just ping the other guy’s belly or sinuses for an update on their physiological or emotional states.

Speaking as someone who has been published in that very same journal (a paper on lycanthopy in harbor seals, actually), I’m gonna go out on a limb and opine that the most fine-grained communication likely to get encoded into a fluke-slap would translate as “Hey!”

See above.

That’s an interesting point. Although there’d need to be some kind of adaptive benefit to constantly mixing up your language like that. Maybe dolphins are very wary of surveillance (which might be especially problematic for a creature who communicates acoustically in a murky medium). Maybe they change their words as a form of active encryption…

If you recall, that whole series was annoying as hell. Even Schneider, the star of the first season, described it as “childish trash”.

Hadn’t seen that one. And who am I do disagree with “Tour impenetrable tower prodigious brain”?

You don’t even need to invoke that level of nefariousness. Just posit that they’re playing with us like we’re pieces of driftwood– half the time they happen to push us onto shore, the other half of the time they push us further out to sea. For obvious reason, we only tend to hear about the first case.

Things like signature whistles are distinctly different from sonar click trains. But you’re right insofar as both types of sound communicate information. We should definitely be looking at the whole package to get a sense of what passes between those melon-headed little fuckers.

Troutwaxer,

It’s an interesting possibility, but I think that the pictures would have to be radically simplified if they were to be transmitted to the recipient in any reasonable amount of time. I’ve been working with micro-CT scanning and the files are astronomically big – admittedly I’m trying to get as much detail as possible, but from what I’ve seen, even a sketch of my scans would take up a huge amount of space. Dolphins might have some better means of compression than I do, but even so, I find it hard to imagine them transmitting images to one another.

Sending symbols, though, isn’t so hard to image, although how this would be an improvement over “words” (or their equivalent).

Maybe work against surveillance from competing groups. They get to hear everything, including chats about food or sex or whatever.

Anti-surveillance daily-reset crypto-sonar streams for the win. 🙂

otoh:

I am skeptical that anything good can come of understanding dolphins, at this point. We have both shown potential for extremely shitty behaviour; can’t we just be content with these few seemingly-overlapping patches in terran experience-space and just get on with our mutually-unintelligible lives? We don’t have to know everything about everything all the time. Consider also that we are not the only species tuple to not understand each other. It seems like most species (or maybe genuses, whatever) don’t understand each other, so maybe there’s a collective adaptability thing going on? Lets nature massively parallelize sapience experiments? I don’t know. I’m just saying there’s a lot of non-mutually-intelligibleness up for grabs; I dunno why we’re so hung up on human-dolphin instances. And anyway dolphins creep me out! >.<

My prev comment is awaiting mod…

I basically just said: STOP SCIENCE, didn’t I? lol…

Oh, dearie me.

carry on then.

I can’t remember if it was in the story, but I liked in the movie Arrival the observation that the aliens might have more than one spoken language. Thinking of all the human languages it’s an utterly, “well duh” moment, but apparently not obvious enough to be part of our common thinking around communicating with other Earth species, or aliens. The idea of continually shifting meanings for sounds within dolphin subgroups is really cool, and the lack of sound privacy in underwater environments makes the need to reduce surveillance by other subgroups through shifting meaning very plausible to me. At least, plausible if dolphin groups act even a tiny fraction as reprehensibly to other groups as humans do to each other…

On the other hand, would having a continually shifting language have to have utilitarian adaptive benefits? How much utilitarian adaptive survival value is there to making music? The sounds don’t “mean” anything, and often the lyrics are more the ambiguity of poetry than story. There’s no baseline adaptive value there, but no one pulls chicks faster than a rock star (Melissa Etheridge included, although I don’t know how things work in this respect for straight female stars). Those guys are rich doing something that has no survival value. But even ugly guys playing shitty clubs punch above their weight in this respect. I remember reading some psychologist, on why people find musicians attractive, speculating that it was the underlying physical attributes and skills that were necessary to make music that were actually the draw, but that actually seems more of a stretch to me than simply that we’re out here in this beautiful and terrifying world, and music somehow enhances or mitigates our awe and fear, or simply reduces boredom and ennui. To do this requires intelligence, and there is “meaning” in what’s created, but I’m not sure if a rational, reasoning being wired very differently from us would “get” why we listen to music.

I’ve often wondered if the dolphins don’t communicate by broadcasting pictures with their sonar. It might not be “photo quality” sonar, but something more like a sketch or caricature.

I don’t know enough about sonar to know if this is even technically possible, but I am instinctively dubious. How would this work? Dolphins have a directional beam emitter and non-directional receivers, so I could easily sneak a jamming signal in from off-axis (like a sidelobe leakage in a normal radar). But how much detail can dolphins detect? They don’t raster-scan either at the transmission or the reception end. Based on that, they could do size and distance, and maybe rough bearing based on “can I detect it or not” but it’s not like they’re producing some sort of terrific sonar image.

I think Prof Watts would have a lot better detail and a list of references, but I’ll try to have a go at the question of transmitting images.

I get the impression that dolphin sonar isn’t all that different from what we have today, other than that it’s a hell of a lot better. Take the example of medical ultrasound (“MU”). Even though we’ve got really good computers, mostly MU is most effectively used emitting and collecting very nearly in a plane rather than in a cone. The skilled user then assembles the collection of planes collected into a volume, in their mind’s-eye, rotates the emitter/collector unit, scans from different angles, etc. Watching dolphins, they’re doing something quite comparable but where we humans are using skill and imagination to assemble that picture, the dolphins are using an evolved (and rather old and refined) system. Whether they “see” it as we see a 3D model if we’re trained users assembling a series of plane images in our imaginations, we can only guess. But we’re pretty sure they have that model, I guess? But so much of the data they collect as returns from the click train, in interpretation it has to have a lot of information not just about direction and range, but also about texture. That much has been known for a long time. Still, if you were a dolphin trying to transmit a picture to another dolphin, would you include all of the texture information on top of the distance and ranging? Maybe you don’t need to do that. Additionally, you probably don’t need to be nearly as loud as the original clicks. Besides… Dr Watts, do we know whether or not dolphins can modulate their clicks sufficiently as to mimic the overtones which texture would impart to echoes? If they can’t do that, sending a “picture” might be harder than we’d imagine. Also there are a lot of other echolocation effects I don’t know they can do, though redshifting or blueshifting would probably be pretty easy. But a really good question might be, how would they develop the capacity to do this, or why would they do it. If one was trying to give a warning such as “here comes, quickly, something large and non-tenuous”, why would it? Any other dolphin close enough to need the warning, could perceive that same thing almost as well.

Off topic but this cheeky chappie claims that consciosness is a solved problem. it’s merely the compression algorithms used to distinguish self in neural networks (And thus that existing neural networks already have some form of consciousness). On the one hand, it solves the whole “what is it good for”, on the other, it’s a little anticlimactic. If true.

Oh, well. Thanks for sticking to your promise and writing a bit about this. I tend to revolve around this ‘dolphin problem’ (in very wide, non-scientific sense) for quite many years. Initially I was attracted into dolphinarium, then hated it and went on trying to find _anything_ what may help (ex)captives. I was nearly sure I found it (Ken leVasseur’s views – http://whales.org.au/published/levasseur/index.html ), but then it turned out real-world humans (especially scientists, on whom I put a lot of hope, following this..intellectual-worshiping tradition) much less capable of changing _their_ behavior towards captives, and thus no matter how accurate and progressive idea was – it doomed to non-implementation, or failed compromised implementation…

So, by now I don’t see dolphin language same way I saw it in 2002, say, but still think it really important factor to try and have ..between..dolphins (or perhaps other non-humans) and..me/other humans (yes, it tend to be egoistical, but this interspecies language thing already changed some humans in such way they much want it, and I obviously can come up with some use-cases for dolphins/cetaceans themselves..in world dominated by asshole humans, but where not all humans are asshole at their deepest core).

I’m from Russia, therefore I can read few things in russian, in addition to english studies most popular in english-speaking part of the world.. Ken found out Markov, and I followed this path to some degree. There are more popular (in eng. speaking world) sci. authors on this path (information theory as way to detect language), like McCowan, and I definitely can say idea about human-created middlelanguage never get enough thinking/practice in exUSSR compared to USA and co. So, I’ve read mostly english texts by Savage-Rumbaugh, Pepperberg, etc – as they were listed in Ken’s references list. I found them very interesting, especially late Savage-Rumbaugh on social aspects of language and possible natural acoustical (?) language among bonobo apes…But all this remain fragmentary and incoherent – in sense scientists so much focused on _studying_ language or anything they completely ignored bigger reality around them..and their own behavior. It was very sad realization for me, because I found myself without any working real-world example where _intelligence_ (as promised) actually work whole way from discovering inconsistency to self-change. No matter how good you can reason – if you have no bravety to do/change something – it will only very partially reflected in way you act, live, and contribute to current currents.

Ken tried to re-use idea about whistled language as found in some human societies, but Peter (you) showed there was also _click_based (specialized) language among other humans, too, and I really like idea about dolphin (cetaceans) teaching us their language/worldview (as expressed in sci-fi book of Derek Bickerton “King of the sea”). So, while in humans reasoned thinking alone turned out to be weapon more than tool of mutual understanding – I still like to use it (reason) to try and find ways out of current situation…

Having worked on three different interspecies communications projects including Lilly’s project JANUS, the biggest problem to overcome in communication here is the lack of overlap in audio/hearing frequency ranges between our respective species, human and dolphin or more generally cetaceans.

We aren’t able to fully comprehend what they might be saying because we cannot fully hear what they are saying.

As another example of this, I recently learned that rats “laugh” at 50 Khz when they are tickled. Without translating this into human hearing, we had no idea they did this.