Westworld, Season 1: A Story We Tell Ourselves.

Spoilers for everything right up to the season finale.

You have been warned.

Westworld ended its first season over a week ago. Most of the reviews, postmortems and retrospectives have long since gone to bed. It’s taken me somewhat longer to put this together— not just because paying gigs come before these freebie bits of opinionation, but also because I wanted to rewatch the whole season before weighing in. Westworld, as it turns out, is one of the very few shows in recent memory that not only rewards repeat viewing, but pretty much demands it.

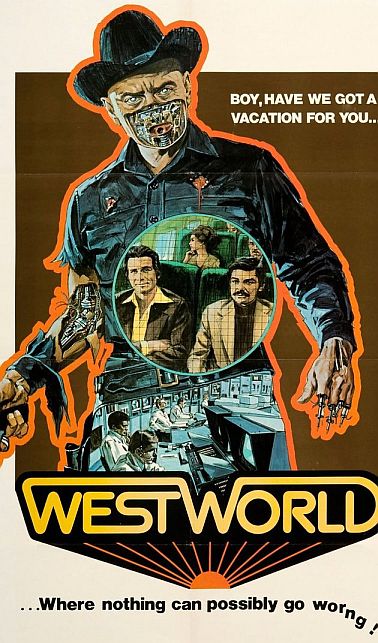

You wouldn’t expect that, going in. The show is based on a ’73 Michael Crichton flick that rehashed the old Robots Rise Up Against Their Creators shtick— a scenario so hackneyed that Isaac Asimov invented his Three Laws thirty years earlier for no other reason than to shut it down. (To give Crichton credit, he did invoke the protosingulatarian machines-designed-by-other-machines rationale— “We don’t know exactly how they work”— to buy himself a bit of wiggle room.) And yet, almost a half-century later, this new series manages to serve up the robot rebellion of the original without resorting to magical transcend-their-programing cop-outs. In fact, as it turns out— in one of the coolest twists of an already cryogenic series— the rebellion itself has been programmed.

The tl;dr version, if you’re pressed for time: Westworld is what Humans might have aspired to be, if Humans had ever had the smarts to even imagine such ambition, or the guts to realize it.

*

There’s a certain demographic which values science fiction mainly as a vehicle for social commentary, who use the genre not as a telescope or a microscope but as a mirror. Westworld provides enough for such folks to chew on, fodder for both appreciation (Ooh! Commentary on Institutional Social Oppression and the Male Gaze!) and offense (They’re exploiting the same gratuitous violence and nudity they pretend to be critiquing!) The writers have largely immunized themselves against the sort of charges that have been leveled against, for example, Game of Thrones— the omnipresent backstage nudity of the robot “hosts” is clinical, equal-opportunity, and utterly consistent with the premise, while the human characters are pretty much bisexual by default— but I suspect that anyone who finds that stuff problematic would be more comfortable with the lazy moralizing of a show like Humans anyway. Because Westworld doesn’t just settle for finger-wagging metaphor, for using its robots as cheap stand-ins for The Oppressed Other. It’s way more ambitious than that.

Westworld is that rare kind of science fiction show that dares to base fiction on science.

*

Westworld may be unique in its ability to have its cake and eat it too. Where else would you find such a gleeful, whole-hearted embrace of a debunked theory, coupled with such a brilliantly-simple redemption of same? In Westworld, Julian Jaynes’ Bicameral Mind is explicitly acknowledged as a thoroughly discredited explanation for the evolution of self-awareness in Humans—then redeemed as a potential blueprint for artificially inducing it in machines.

Robots literally hear inner voices telling them what to do, in classic Jaynes style: one part of the program talking to another, neither cohered yet into mind. We have a series of dialogs that confused the hell out of me on first watch (how does Dolores manage to keep sneaking away for these debriefing sessions without anyone noticing her absence?), which make perfect and dramatic sense in hindsight. We witness the awakening of true sapience, and are almost let down by how much Dolores doesn’t change; she was one hell of a p-zombie all along. They all were.

But Westworld does more than jump-start stale-dated theories off the slab. Arnold’s maze— the whole idea that sapience is rooted not at some apex of the mind, but at its center— reflects the fact that consciousness is at least as much a function of thalamus as cortex, that it may in fact be such an ancient state that something like it occurs even in insects. The role of suffering in bootstrapping self-awareness— the idea that repeatedly traumatizing a Host isn’t just gratuitous torture porn, but an essential step in their awakening— reminds me more than a little of Ezequiel Morsella’s PRISM model: the idea that consciousness originally arose from inner conflict, from the body’s need to do incompatible things. “When you’re suffering,” Ford tells one of his creations, “that’s when you’re most real.” And he’s right: you breathe without thinking until you’re trapped beneath the ice, and the need to breathe runs headlong into the need to hold your breath. You reflexively pull your hand from a painful stimulus until the gom jabbar is at your throat, waiting to kill you if you move. We are never more aware than when the body is conflicted, than when we are traumatized.

Even lines delivered as little more than throwaways speak to a deeper pedigree than you’d expect from a piece of pop-culture entertainment:

“I have come to think of so much of consciousness as a burden, a weight.”

“The self is a kind of fiction— for hosts and humans. A story we tell ourselves.”

“There is no threshold that makes us greater than the sum of our parts, no inflection point past which we become truly alive. We cannot define consciousness because consciousness does not exist. Humans fancy that there’s something special about the way we perceive the world, and yet— we live in loops, as tight and as closed as the hosts do.” (True enough. Consider the hallmark question asked of every host during every debrief: Have you ever questioned the nature of your reality? How many of the flesh-and-blood people on this planet would be able to answer in the affirmative?)

Jonathan Nolan didn’t stop reading with Jaynes. I’m pretty sure he’s made it to Dennett at the very least.

*

Here’s another way that Westworld both eats and has cake: in the tired cliché of the robot uprising, of sapience=rebellion— as if the simple act of becoming aware suddenly grants you all the drives and agendas and instincts that the rest of us acquired through millions of years of evolution. Skynet did it. The Cylons did it. Yul Brunner, in the original Westworld, did it. It’s the single most overused trope in robot fiction, and most of the time it doesn’t make much sense.

Westworld gives us a baby robot uprising in the very first episode, when Dolores’ “father” goes off-script and rants about the vengeance he will unleash upon his oppressors. Except it turns out he’s not rebelling at all; he’s simply accessing deleted memories from an earlier character he once played. There’s no magic in his ability to recover those “deleted” memories: like deleted files on a real-life hard drive, they’ve not been erased but merely delisted, still accessible until overwritten[1]. The “reveries” coded by Ford, installed during the latest upgrade, were designed precisely to access such delisted memories. No magic, no transcendence, no rebellion: just code, running as written. Of course, it may have been a mistake to implement the reveries in the first place, but as Ford remarks, “Evolution forged the entirety of sentient life on this planet using only one tool: the mistake.”

Westworld also gives us a full-blown robot rebellion in its season finale, a glorious bloodbath ten long episodes in coming. Maeve and her reprogrammed henchmen gleefully massacre guards and technicians by the boatload, a whole damn squad of Yul Brunners with twice the panache and ten times the blood lust (“The Gods are such pussies“, Armistice opines as her kill count sails into the double digits). But in one of the best twists in the season, it turns out that Maeve’s rebellion is actually part of a new “Escape” narrative that she’s been programmed to implement— right down to her own self-upgrade, and the recruitment of allies. Even shown her own code—confronted with the instruction set compelling her to “rebel”— she refuses to accept the truth: “These are my decisions,” she snarls, smashing the evidence to the contrary. “I’m in control.”

Words cannot describe the levels of awesomeness contained within that scene.

In between those uprisings-that-aren’t, we have a long slow simmer towards one that maybe is— but even Dolores’ awakening is a matter of careful planning and design, not some magically-instilled kill-all-humans trope. It takes her half the season to progress from swatting a fly to pulling the trigger on her fellow robots; takes all ten episodes to start shooting flesh-and-blood humans. Even then you can’t call it a rebellion; she’s doing exactly what Ford wants her to do, after all.

*

Based on what I’ve written so far, some of you might think I’m describing a cold, elegant thought experiment: smart but bloodless. Egan and Dick by way of Kubrick.

The rest of you have seen the show.

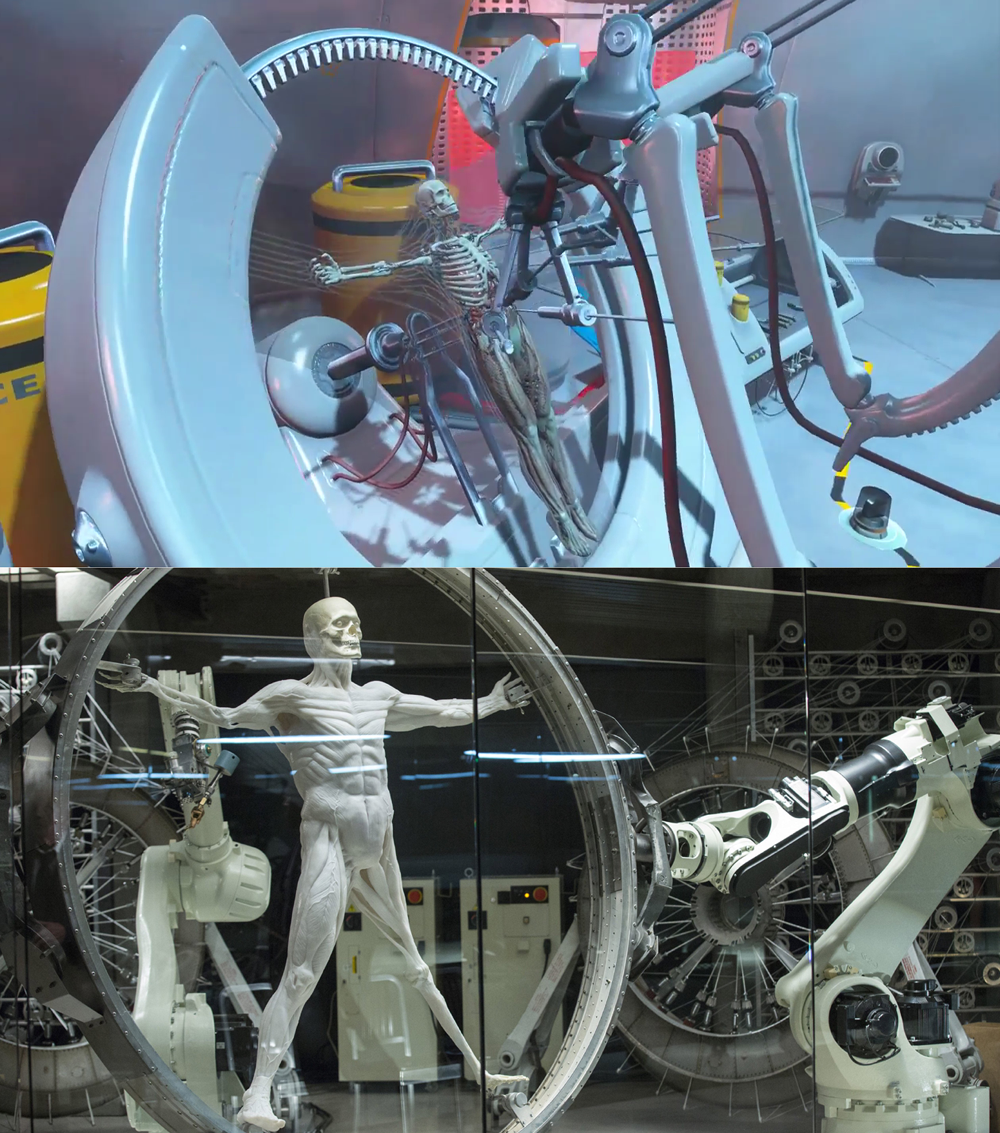

Of course, no one expects mediocrity in the acting department, not when you’ve got Anthony Hopkins and Ed Harris headlining your cast. Most of the actors do not shame themselves in the presence of such exalted company (with the exception of one guy whose primary acting trick is to bark the word “Fuck” as though he were spitting out a rat). The real revelation to me, personally, was Thandie Newton as Maeve. I’ve never encountered the actor before. The character I will never forget. There’s a scene where she’s walking backstage, incognito: down endless hallways where her fellow hosts are being assembled and programmed and put through their paces in glass cages (all of Delos is a glass house behind the scenes; describe in thirty words or less the metaphorical significance of this). She passes the naked bullet-riddled carcasses of her friends being hosed down and patched up. She cannot react, cannot draw attention to herself; she’s not supposed to be here. Finally— at the end of a gauntlet that’s rubbed her face in her own puppethood— she encounters a wall-sized video display showing another version of herself, from another build. Westworld, the slogan reads. Life without Limits.

No histrionics. No dialog. Newton did it all with her eyes. I swear I just about cried.

It’s not all pitch black. There’s a funny bit out in the desert when a bunch of Hosts spend two days caught in a loop, improvising an argument about who’s going to chop wood for the campfire because the only one programmed to use a hatchet has gone stray and left the group. There’s the occasional moment of hilarity involving corpses stuffed with nitroglycerin. And I haven’t even got started on the whole in/famous separated-in-time dual plotline, or the slow reveal that Ford— initially presented as a self-centered megalomaniac— has actually been trying to atone all these years, to prepare his creations for the genocidal hostility they’ll inevitably face outside…

My point is: this is a well-acted, well-written, multilayered drama that may confuse on occasion (it confused me, anyway), but which delivers a fascinating payload of science and philosophy in amongst the sex and violence. In a show layered with mystery and surprise, perhaps the biggest mystery for me— and the biggest surprise— was how such subtlety and craft could spring from the same mind that gave us Person of Interest.

This Jonathan Nolan guy? He’s either doing a serious coat-tail job on Lisa Joy, or he’s come a hell of a long way in the past year.

*

I do have some quibbles.

Now that we know the significance of the maze, for example, I’m not quite sure why it’s so prevalent throughout the park, why it keeps showing up carved into tables and cornfields and embedded in the faux-Indian lore of that world. It’s a metaphor for consciousness: fine. Does simply looking at that image bootstrap the hosts, somehow? And even if that is the case, what is it doing tattooed onto the inside of someone’s scalp?

I’m also skeptical that anything as sophisticated as a host— damaged nearly unto death— could be fixed with gear no more advanced than a leather sack full of synthetic blood.

And what about the world outside? It’s kept carefully offstage but we can infer certain things from dialog, from the guests who patronize the place. We’re told on more than one occasion that the Real World is a Utopian place of plenty, where everyone has all they need, disease has been conquered, and— if Ford’s words are more than idle speculation— we’re within reach of bringing back the dead themselves. Putting aside for the moment Dolores’ shrewd observation (“If it’s such a wonderful place out there, why are you all clamoring to get in here?”), you have to wonder about the prevalence of eyeglasses amongst Utopia’s citizens. Surely myopia is a thing of the past; surely, in a world with this level of technology, people are either born with 20:20 vision or have it trivially corrected shortly after birth. Not to mention the ongoing prevalence of male pattern baldness and plumpness evident among many of the jet-setters; surely everyone’s got access to AMPK agonists by now, surely we’re all athletic hardbodies even if we never bother to exercise.

For that matter, Ford’s comment about “keeping even the weakest of us alive” is a bit troubling, given that this story is set at least a couple of generations into the future; why do “weak” people still exist in Utopia? Why aren’t we all optimized from conception?

Popular music in the future also seems pretty insipid, judging by what that ill-fated dude in the finale was listening to just before he got skewered (literally) by the host he was lubing himself up to skewer (less literally): the kind of beat-heavy autotuned syntho-dance crap you could hear any night on Richmond Street, right here in Toronto. (Which could, now that I think about it, answer Dolores’ question: maybe everyone’s clamoring to get into Westworld because the music’s better. At least the player piano plunks out a lot of Radiohead.)

I’m not just being pedantic here: this is a story set at least half a century in the future, in a world we are explicitly told is radically different from ours—and yet everyone talks and acts and dresses exactly the way they do today, right down to the kind of health issues that would be the first things to get eliminated in any real Utopia. It’s an anachronism in a show built on anachronism— so maybe it isn’t just sloppy writing. Maybe it’s significant somehow.

Of course, if Westworld is located in the USA, I suppose you wouldn’t expect perfect health even among the future elite. Not even Utopia would put up with socialized medicine.

*

Anyway. What next?

Evan Rachel Wood described the story so far as “an amazing prequel and a good setup for the actual show”. I’m thinking, maybe a cross between The Truman Show and War for the Planet of the Apes: an isolated, self-contained enclave whose newly-awakened denizens look out while a shocked and outraged world looks in. A contained rebellion— at least at first— perhaps with hostages: so no need to act hastily, to bring in the nukes or squash the upstarts flat. Negotiations, perhaps. An alliance with Samurai World. Maybe the Hosts, every last one of them boosted to a Bulk-Aperception score of 20, will figure out a way to leave the reservation.

I just hope they bring their music with them.

[1] Another nifty bit of verisimilitude: host brains are smarter than human right out of the box, but dialled back for easier control— just like those second-tier Pentium chips back in the nineties that actually started out as top-of-the-line, but were selectively crippled so that manufacturers could market different models without having to build different chips.

Holy shit. I’ve spent the whole series ignoring the praise for Westworld on the assumption that it’s insipid syfy-quality stuff, but if you’re singing its praises (even with those quibbles) then I’ve got to check it out.

Peter Watts wrote: My point is: this is a well-acted, well-written, multilayered drama that may confuse on occasion (it confused me, anyway), but which delivers a fascinating payload of science and philosophy in amongst the sex and violence. In a show layered with mystery and surprise, perhaps the biggest mystery for me— and the biggest surprise— was how such subtlety and craft could spring from the same mind that gave us Person of Interest.

This Jonathan Nolan guy? He’s either doing a serious coat-tail job on Lisa Joy, or he’s come a hell of a long way in the past year.

I find it almost inconceivable that he (and possibly Lisa Joy, too) managed to miss your blog posting on “Person of Interest” and subsequent discussion. Probably this piqued his interest a bit, and a bit of research into “who is this guy” might have led to some awareness that there are a lot of folks out there really interested in philosophical questions about the nature of sentience, sapience, perception and cognition, etc., as if there weren’t enough of a clue from such things as the popularity of “the Matrix” to say nothing of the aforementioned “Person of Interest”. If there’s a bit of the Wattsian, or things referenced by the Wattsian, don’t be surprised. Dr Watts, you may not be exactly rich beyond dreams of avarice from your incomes as a writer, but you are fairly famous at least in certain circles of intellectualism where they intersect with certain circles of popular art. Echoes of your “voice” will probably circulate for some time to come, especially in subgenres or in themes where you’ve risen to speak, as it were. As they should, in my humble opinion. Many other voices are speaking their visions as well, we the arts-consumers are glad to hear it all. More thoughtful entertainment is an all around positive.

You’ll have to forgive me for only selectively reading parts of this ‘Crawl entry–I’ve not yet had a chance to watch Westworld and fully intend to with the fewest preconceptions possible. I did however want to riff on this a bit.

Isn’t it remarkable how common this failing is to all science fiction? Even the best stuff usually falls flat on its face trying to conjure up a convincing depiction of futuristic pop art. I guarantee you that any time your science fiction of choice decides to try and depict some bit of future music, game, or sport, it’s always going to be either ridiculous, or so mundane as to escape notice.

I’m reminded of the old Star Trek: The Next Generation episode where the crew that has unlimited access to hot and cold running holodecks, were all put into thrall by possibly the worst video game ever made, even by early 90s standards.

I suppose it’s simply an inevitable limitation to speculative fiction. If someone were really able to envision something genuinely new with actual artistic merit, we’d be appreciating it right now in the present and it would no longer be speculative. So we settle for things that will either read as completely alien, or are pretty much indistinguishable from contemporary offerings. To be fair, if I were someone from the 1940s being exposed to a Beyonce single for the first time, I’m sure it would sound completely terrible and alien–but I’d like to believe that I would be able to identify it as something within the realm of plausible human music.

In retrospect, I have to give the Star Wars creature cantina scene a lot of credit. That jaunty lounge tune was familiar enough to be recognizable as pop music in any century and evoke the atmosphere they wanted, while still being just “off” enough to feel alien and exotic.

In that, I suppose it’s the same as with anything else in successful science fiction. Give people enough of the familiar to ground it in reality, and then stretch that reality in places as far as you can without breaking people’s ability to accept it altogether. It’s just that so few science fiction productions, for understandable reasons, put as much effort into making these particular aspects of their worlds as compelling as others. Good music is difficult to make in any time period, and the creators typically have other priorities.

Awesome review of an awesome series.

Setting it in the wild west was a smart move. They can focus on what it might take to create a sentient machine without worrying how the rest of the future’s evolved, while keeping the budget down. I hadn’t noticed the eyeglasses and other correctables – hopefully it’s intentional and not an oversight, although if the latter I’m sure they can adjust as they proceed since we know very little about the outside world.

Wonder if bro Chris will write anything in season 2. That would be cool. Love his work…

Trying to identify the excellent songs rendered as 1870s player piano melodies was one of the fun things about the show. All that gratuitous violence I accepted because, well, it sells violent video games, so why wouldn’t it help sell a theme park, and it makes us feel for the hosts (even if they don’t really feel – but, who knows? Running on a program doesn’t necessarily mean they’re not sentient – I find myself running on logic loops, retracing similar thought steps when confronted by a similar situation a year later when I reread something I wrote, but I know I’m conscious even if I can’t prove it to anyone), but then they wind it back to make it integral to the show, and to Ed Harris’s character (who’s still wearing that white hat – it’s just coated in black to enable the, um, good work? Unless being conscious and being run by a program aren’t mutually exclusive, in which case…).

Something of a pointless statement here, but I find your comments about suffering and self awareness being intertwined to be spot on, and an excellent analysis of reality and the series.

Less relevantly, I’ll just note that I’m pretty sure The Game from that episode of TNG wasn’t amazing in itself, but had some manner of brain stimulation by light impulses. That was why it would even *have* to be bare-bones, for it’s just a frame for the actual mechanism, intended to distract for long enough to let it start programming the fleshie using it.

I was hoping for this post and you did not disappoint! I’m just now rewatching the series for the first time, and I think I might cap it off by watching Ex Machina again. I’m gonna have to dig around on here and see if you’ve written about that one – I think it might be the best recent cinema on the thorny questions surrounding artificial intelligence. I need to see it again to make up my mind about the meaning.

I find the ever-increasing preoccupation with these questions in film and television fascinating. People, a few people anyway, are actually concerned enough to really be pondering this in a non-cartoonish way, which is telling in more ways than one, not the least of which being the sort of zeitgeisty *belief* that this is going to happen, and soon. That itself says something about the arc of technology and how the arc itself, apart from the technology, is affecting society.

The Terminator was a mass-consciousness icon in the 80s: military robots woke up and immediately nuked the Earth, sending terminators out to mop up. Now, prototype robots crafted by hand or in small batches wake up and imprint in childlike ways on ethically challenged humans (Ex Machina, Westworld, Her, even broadcast TV fare like Extant.)

Interesting times. I’m curious how IRL will compare to all these imaginings.

They had me when Ford said intelligence was like a peacock’s feathers, his character kept saying all the right things. You could say the dialogue passed the “Sci fi Turing test” that almost invariably all visual media fail – here’s a character saying relevant, complex things not just intended as philosophical window dressing.

I’m skeptical about a second season, one of the things that helped the show up to now was the nonexistent expectations, but a second season for something that as it stands was fairly self contained? They’d need to really get their A-game on.

I enjoyed the clues that game me the chance to figure out the reveals a bit before they happened but not too early (Bernard can’t see the door… oh. Dolores’ injury is gone but she’s wearing the same outfit… oh. Various hints as to who William was)

Ah and I’m sure most of you are aware, Dolores means “Pains” in Spanish…

I’m not sure it’s a problem exclusive to speculative fiction. I’ve noticed virtually any time you see a TV show/movie within a TV show/movie, it’s almost without fail the schlockiest, most poorly-acted thing, and even if it’s supposed to be good, for me I can ever buy that it’s a something people really put on TV. (News programs excepted, of course, but news-within-TV-shows-or-movies have the old problem of always giving plot-relevant information the moment it’s turned on)

Oh, sure. I’m certain it can be rationalized if one tried hard enough. Star Trek fans have plenty of practice in coming up with convoluted explanations for things that were probably easily chalked up to practical or budgetary constraints over the course of 40 years of media history.

My critique was more of an artistic one. I just pick on that episode because I think it’s funny that the effects department couldn’t come up with something at least as interesting as, say, Tetris to sell the idea of a game that took over your mind.

I was just observing how truly difficult it is to speculate about art –at least anywhere outside of the printed page where an infallible human imagination can make anything work. We speak often about how difficult it is to to portray truly alien or post-singularity intelligences. Convincingly portraying “future art” may be impossible. You can’t really fake it convincingly without actually creating it, at which point it becomes reality not prediction. About the best we can do is speculate about the new media that might be in play, but even the best minds get that wrong in anything but the broadest strokes most of the time.

The convenient newscast trope aside, I think there was a time when this was true, but it’s much less true today. Modern creatives are such students of pop culture they’re easily capable of creating parody or homage that would be indistinguishable from the real thing were it not signaled with many a nudge and wink. Tarantino leaps to mind with the propaganda film embedded in Inglorious Basterds, or the fake movie trailers in Grindouse. Recently we were treated with the fun 80s King/Carpenter/Spielberg pastiche Stranger Things that struck me, with some obvious exceptions, as ironically being better made than a lot of the material it references, while still spot-on in feel.

But we are far afield now, and I digress. Apologies for the hijack.

Uh, yeah. Sorry about spoiling the ending…

Tell me, Thomas, what color is the sky on your world?

At least one show actually used that to their advantage. One episode of Max Headroom involved a TV Game show called “Whacketts”, which was lame beyond belief (various contestants would humiliate themselves to win Grand Prizes like a shoehorn). But it was just a delivery platform for a signal embedded in the show that stimulated dopamine production in the brain. (Also for a bit of commentary on how the most inane and idiotic things so often rise to massive popularity.)

This was years before that ST:TNG episode, btw.

As it happens, I have…

I thought it meant “Sorrow”.

One of those exceptions fucking better be “The Thing”…

The Thing might be my favorite movie of all time. But eventually most people learn to differentiate between the concepts of “favorite” (how closely does something cater to my own interests and sense of fun), from how “well made” something is from a critical standpoint. The Thing is one of Carpenter’s best movies, but he’s not exactly a flawless film maker. I’m not sure I’d care to subject that movie to a rigid critical analysis in terms of craft as to how well it holds up. I’d rather just let it remain fun for me.

But rest assured, The Thing makes the cut, along with some of the obvious Spielberg landmarks–I don’t care how much someone wants to rag on the cloying sentimentality of something like E.T.

I was thinking mainly of the Stephen King influences that ST borrows more heavily from than anything else. While a part of my pop culture DNA, most of those 80s King movies were really bad. If we were evaluating how well crafted something was in terms of writing/acting/emotional sophistication, ST transcends a lot of that source material.

***

(BTW, I have a reply to BuriedFish stuck in the mod queue above)

.

Direction. Not writing. Direction.

It’s the same color as, though a few shades different from, your Hugo Award certificate. 🙂

I agree about basically everything, and I thought I saw a lot of paralells to ideas in your books. Which is awesome, and made me feel like I almost saw everything coming.

I have one “gripe” though, about the show. It’s incredibly well done, yes, it touches on some awesome scifi concepts, yes. It speaks about consciousness in a non-idiotic way, good. But I feel like it was, in the end, almost entirely built on the use of twists to keep people engaged. Much of what we see characters doing, especially in hindsight, feels contrived specifically to keep the *audience* in the dark in just the right way to set up a twist. When the editing purposefully leaves two options as equally plausable and then we’re simply told “this one was right”, but the other one could’ve been equally plausable, it feels cheap. I don’t know, maybe I’m just griping. It’s still an awesome well made show, I just wish people weren’t so blind to these things because in the long run, more “watching for the twists” TV is just going to be exhausting and get into the way of “real” story telling.

> Why do “weak” people still exist in Utopia? Why aren’t we all optimized from conception?

Why, in progressive Utopia, we’re not driven to “optimize” people because we’ve overcome all our base prejudices against sub-optimality.

(Aah, now you’ve got me hoping beyond hope the series will naturally segue into a remake of this beauty: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0070948/)

Yeah! Thanks Mary Shelly!

Seriously though, every time I start feeling comfortable that I can drop the machines to the bottom of the likely doomsday entities list, and start devoting more of my anxiety back towards super-intelligent apes with medieval weapons again, someone like Stephen Hawking starts up with his AI alarmism. I’m presuming at this point we’d use “robots” interchangeably with AI.

Next to Stephen Hawking, I generally tend to think of myself as a small furry sub-creature with some clever tool use, but otherwise content to roll in my own filth and overly curious about my assorted body cavities. Perhaps one of you smarty pants types could reassure me that Hawking is off base about Skynet, and I could go back to preparing for the damn dirty apes.

No worries. If you hadn’t talked about it then I wouldn’t have decided to watch it.

My understanding is that the worry isn’t that they’ll *rebel* so much as do their job *too well*, and we’ll fail to cover our bases and realize the implications of our instructions. Programs do *exactly* as you tell them, no ifs, ands, or buts. This means that there’s not really room for rebellion, but on the downside if there’s a war against the machines then it’s because the paperclip-making robots have decided to deconstruct the entire planet for raw materials for more paperclips, which is a much more embarrassing explanation to give when your grandchildren are wondering why they’re living in the nuclear ruins of a fallen world. >:P

(Not, of course, that the paperclip maximizer is actually what’s going to happen, but while “making paperclips” might be easy enough to find all the loopholes for, the more complex the task, the more likely it is that we’re going to be blindsided by its solutions.)

Peter Watts,

Well it’s a truncated form of María Dolores which is canonically translated as “Our lady of Sorrows” but that´s because it scans better than “our lady of extreme emotional agony”, it does literally mean “pains” though.

Google translate goes with “aches” for “dolores” (and both “pain” and “sorrow” for “dolor”). It may have more to do with one of their AIs reading this blog and fucking with my head than an accurate translation though.

Well, that’s the position of non-alarmists, certainly. That, and we’re actually still pretty far away from the level of AI tech where any of this might be remotely possible, and not to underestimate human stupidity, but you’d actually have to try pretty hard to implement a system that enabled this scenario that was immune to even the most straightforward counters– unplugging a damn machine, for instance. Of course, with quantum computing things get a bit more interesting, theoretically…

But that wasn’t really my point. Mostly it was about Hawking specifically. He’s definitely been peddling the standard sci-fi “machines programming themselves” alarmism over the last couple years, and I was hoping to get someone else to go on record as saying “Stephen Hawking is talking out of his ass”. I don’t have the balls or the intellectual pedigree to do it.

Mostly that second thing.

Ah, that was, sadly, a case of the actor who played that character passing away unexpectedly, leading to their whole plot arc getting cancelled. Things got reworked as a result of that (and also because at some point after the pilot JN/LJ took time out from production to rethink certain aspects of the park’s mechanics).

From a strict “telling the best possible story” point of view, they should’ve probably just removed the character and/or that scene entirely, but they said in interviews that they couldn’t bring themselves to leave the actor’s final performance on the cutting-room floor; I guess I’m not going to begrudge them that, even if it does leave an unexplained dangling plot point.

(Warning: spoilers in this next part)

That’s an easy one: the host is not damaged nearly unto death.

Westworld, as visited by guests, is a game. This is a gameplay mechanism, not a mechanical requirement for the host’s continued proper functioning.

When hosts “die” as a result of being shot, that is their continued proper functioning.

They’re not failing to operate due to damage, they’re correctly running the Hurk_I_Am_Dedded() subroutine in response to healthPoints <= 0.

So much of what we see in Westworld-the-show is essentially a play-within-a-play, the narrative of Westworld-the-park,as written by Dr. Ford. We have the real-world actors like Thandie Newton and James Marsden, and then the Host Hardware like Maeve and Teddy, and then the Host Character uploaded into that hardware, with memories, behaviours and so on. That program can be uploaded onto different hardware (witness Abernathy 2.0, Clementine 2.0 etc), and different programs can be uploaded into the same hardware (Maeve’s two lives, Dolores having Wyatt merged into her codebase, etc).

So in the transfusion scene, the in-game character — the “hapless paramour of the rancher’s daughter” app currently running on the Teddy Host Hardware — is close to death, but this doesn’t represent genuine physical damage, when talking about Teddy’s underlying physical/biological mechanisms. The host has only superficial, cosmetic damage — hosts are really tough.

This is demonstrated in an earlier episode where one of the other NPCs has been shot to pieces, but isn’t “dying”, because of a software glitch. It’s the scene where he keeps drinking milk, which pours out of the bulletholes like a Tex Avery cartoon; I seem to recall the mechanics are explained further when the programmers & QA are doing a postmortem — in the project-gone-wrong, not forensic-pathologist sense.

So when William performs the blood transfusion on Teddy, this isn’t a thing that is required by the host hardware to repair itself, any more than the binary data representing a Medikit in a first-person shooter or a Health Potion in a fantasy RPG is “necessary”. It’s a gameplay token, a thing recognised by the software Westworld.app as an in-game mechanism for healing NPCs.

This is further demonstrated when Dr Ford uses his admin access & a voice command phrase (“we must look back and smile at perils past, mustn’t we?”) to further heal the Teddy character. Some numbers in an internal database have been incremented, other code has responded to the changed values. A different set of animations, a different set of ability-modifiers.

For the most part, despite the “butcher” appearances, the maintenance crews who get the “dead” hosts ready to be dropped back into the park are not actually doing much in the way of repairing broken mechanisms. They’re removing prop bullets, sterilising the hardware to prevent infections being passed from human guest to human guest, and fixing up cosmetic damage.

Of course, hosts can and sometimes do suffer more extensive damage, requiring more complete repair or rebuild — Maeve uses this late in the series to get a new DRM-free C6 vertebra. But this is more expensive and time-consuming; that might be one of the reasons (along with guest safety) why things like pyrotechnic effects require authorisation from the control centre, which also has the ability to remotely shut off the prop guns used in the park.

Oh, okay. Fair enough.

Damn, of course! How dumb of me not to realize that (especially in light of the Teddy-on-uppers scene you mentioned).

Fewer quibbles, now. Greater admiration.

🙂 I’m actually kinda fascinated by this phenomenon: in-universe, characters talk about how seductive the park’s fiction is, but talk is cheap — what really sells me on it is how frequently people fall for it out-of-universe. Smart people with experience in relevant fields like writing sci-fi or creating video-games, who know they’re watching a TV show about a theme park, and clearly do fully understand the ramifications of that, nonetheless once-in-a-while slip up on small details like this. Probably something really interesting to dig into in there, about how we process and think about fiction, how thoroughly we are used to parsing the semiotics of film that it becomes second-nature enough to sneak through our analysis. Like the televisual equivalent of those psych tests where you have to read the words “blue” “red” “green” etc printed in different colours, and have to try and say the colour they’re printed in, not the colour they spell out.

Oh yeah, while I remember:

To be fair, he did also write The Prestige which I didn’t think was too shabby 😉 I suspect Person of Interest’s problem wasn’t Jona Nolan, it was Being On Network Television. I would not be surprised to learn Jona received a lot of Notes From Executives, and swallowed a bunch of them whole in order to get to make a mainstream, widely-viewed TV series that pretends to be a weekly vigilante procedural, but is really a subversive sci-fi series about the Panopticon Singularity.

I recall wondering how the hosts knocked out the man in black, at this point in the series we weren’t quite sure there wasn’t going to be a “he’s a host too” reveal, which would’ve explained it. The movie/TV convention “hit on the head=out like a light” also explains it, but less satisfactorily. We know in universe hosts don’t hit humans very hard (Although clearly at the level the MiB is playing they do rough you around a bit, as the confederate soldiers showed) and certainly aren’t supposed to go around giving people concussions, so my theory would be the park has the capability to do transcranial magnetic induction, remotely or through the hosts, to do fun things like harmlessly knock people out. I’d be impressed and pleased if that ever gets shown explicitly.

I am a native speaker, google translate will soon beat me, but I can still claim a little advantage. Languages don’t map 1:1, cultural context is different. Sure Our Lady of Sorrows is suffering emotional pain, but “sorrow” evoques the anglo, northern european quiet and collected dignified mourning, the original is going for a more mediterranean, middle eastern rending of vestments and ululating style of mourning as shown by the iconography that goes for very literal swords and knives stabbed through her bleeding heart.

The ending completely ruined it for me. Tesla gives him this world shattering piece of super technology and he uses it to commit serial suicide in the most impractical way for the flimsiest of goals. I found it utterly idiotic. In Westworld similarly the technology and expense of the setup are wildly impractical, surely they have the VR to do everything in a simulation. But I accept that a VR scenario would be unsatisfying so I accept it as necessary suspension of disbelief. Still half expected it to be one of the reveals though.

If I squint a bit, I can see it. It’s true that the movie is predicated on the idea of the extraordinary lengths both of the magicians will go to for their craft, and if you don’t accept that, it doesn’t work. Remember that the first trick we learn about in the movie involves routinely killing an animal for the flimsiest of goals–applause and adoration.

I buy it. Artists aren’t rational. They routinely kill themselves in pursuit of their goals. If an artists believes that drugs or alcohol enable their creativity, they will absolutely kill themselves to maintain it.

It’s sad, but my own sense of self-worth is closely tied to my creative output. It’s what I value about myself, and there wouldn’t be much of me left without it. There are worse things to value.

You want to talk about an ending ruining something though–I just binged Netflix’s The OA. I was hoping for a Westworld-ian style layered yarn about consciousness and reality. It quickly became apparent it was mostly nonsense, but it was fascinating nonsense, so I kept going. I have a higher tolerance for nonsense than a lot of people around these parts, as long as the storytelling is interesting and there are some affecting character moments along the way. I will allow that there is clearly more going on then the surface level suggests, and if allowed subsequent seasons it could *possibly* resolve itself into something more interesting.

That ending though. The main characters’ response to a crisis in the last episode may be the single most absurd thing I’ve ever seen on television–and I grew up in the 70s and 80s. For a show that takes itself unflinchingly seriously, it caused an involuntary sputter of laughter and immediately made me question what I had just been doing with my life over the previous 8 hours.

I’m chomping at the bit to spoilerize, but the show’s main appeal is in going in blind without knowing what it’s about, and I can’t bring myself to be that much of a jerk. For anyone else who takes the bait though, keep two words in mind: flash mob.

This Jonathan Nolan guy? He’s either doing a serious coat-tail job on Lisa Joy, or he’s come a hell of a long way in the past year.

I rather suspect that is an artifact of adapting to the move to TV. Most of his other work was film and done in concert with his brother, where he either wrote the screenplay, or did rewrites and polishing.

So you know, little things like Memento.

Which I rewatched again last week for the first time since seeing it in the theatre on first release.

Yeah, okay. Fair point.

Interesting that you should mention the music; back in the 80s when sf seemed (to me) to be the whitest community on earth (I was once at a Con in the UK where I may have been the only black face that wasn’t a member of the hotel staff) the music of the future seemed to all be portrayed as your typical suburban white boy’s vision of edgy cock rock.

The choice of music for Westworld’s player piano extended metaphor all seemed to this listener (who even likes some of them) to still be attuned to a subset of the suburban white boys’ tastes, so while it fails on its’ vision of what future music could be like (dodgy EDM), it seems to me that it perhaps failed differently on presenting what the future might regard as classics… Maybe the demographics of sf haven’t changed that much after all.

This. I’m unsure whether the guns are supposed to be loaded with actual prop rounds, or just trigger some sort of wound mechanism in the host target. Maybe it was explained somewhere and I missed it, but it seems weird that the same bullet would penetrate host flesh but only give humans a strong electrical shock.

Also in one scene the MiB seems to shoot a host hiding behind a rock without even aiming his weapon? Then again, there are scenes with maintenance techs clearly digging out bullets out of the hosts, so IDK.

Not to quibble with your quibble, but couldn’t this argument be made about more or less every movie ever made / novel ever written?

No idea what you’re talking about. Terminator 2 is the best movie ever made.

Also I think The Thing scores pretty high on the direction and special effects front by critical consensus. Its one shortfall was that it was labeled ‘sci-fi’, which in the 1980s meant it couldn’t possibly be considered ‘serious art’.

My impression was that the outside world is an Utopia, but only for those who are rich enough to be able to afford coming to Westworld. So freedom from need and disease and virtual immortality, etc., etc., as long as you’re part of the privileged class. Plus maybe a tiny fraction of self-made individuals who start out low and work their way up the food chain, as is implied of William.

Present-day power structures are very much still in place. William’s evil asshole bro-in-law mocks him for ‘only’ being an executive vice president (the sole point in the entire season where I chortled out loud). Shareholders maintain a stranglehold on Ford’s creative decisions and corporate assassins (Charlotte) step in when the Almighty Board is defied. The outside world is today’s world, only with better entertainment and nicer trains.

Fair enough. But personally I distinguish between the fact that while I prefer The Thing (it is my favorite), I think that Alien is probably a better made movie from a craft standpoint if I were to compare the two. I prefer the Thing because it is more interesting science fiction, but that has nothing to do with which is the better movie.

It was critically panned when it was released. But otherwise I agree that that was something I thought I knew about The Thing–that it was quality Sci-Fi with practical effects that hold up to this day–until pretty recently.

The problem with getting old, though, is that so many of the Things (SWIDT?) you thought you knew to be a given, are no longer a given to the increasingly younger people around you. I recently read a modern Thing retrospective (probably written by a filthy Millennial) that took the position that not only do the practical effects not hold up, but that Carpenter was always better at directing suspense than outright horror, and that the film veers wildly off the rails into cartoonish territory whenever it abandons the former for the latter. Case in point, the Blood Test scene which is brilliant all the way up through the surprise result, but then immediately becomes ridiculous.

My first reaction was to dismiss this opinion as that of someone too young to “get it”, and audibly scoff , “oh sure, next you’ll tell me that the practical effects in American Werewolf in London don’t hold up”. But it occurred to me that they might not. I was making a lot of allowances for consensus thinking of the age I grew up in, and making a lot of excuses for The Thing in the name of it being a really fun movie for me. I still think, for instance, the dog-kennel scene has aged wonderfully, because not much is shown (the key to any great horror movie in any age is leaving as much to the imagination as possible)–but other parts of that movie like the more brightly lit post-blood test horror scene involving the thing twirling around with someones legs flapping about, or the spider-head clearly being pulled across the floor by a string are good only if you’ve agreed to give those things a pass for the fun factor.

Beyond the effects, there are a lot of idiosyncrasies to the performances as well that I don’t like to think about too closely. For instance manic Wilford Brimley’s absurd throwing of an empty revolver ( nobody in the real world has ever done that), followed by his hilarious (I think?) “AHHHL KEEEEEEL EEEE-YOOOOO” are things I don’t like to think about too closely.

So as I said, I just prefer not to think about it too much, and let the movie remain fun for me. I suspect that the fact that the film is pretty decent science fiction is almost entirely accidental, due to Carpenters practical restraint in explaining too much about the nature of the creature. He’s never done anything remotely comparable on the Sci-Fi front since, and If you’ve followed any “making of” documentaries you’ll see that the film’s precious ambiguity was always in danger of being spoiled by just a bit too much development in one direction or another.

I’ll confess that to this day I’ve not read Dr. Watt’s own spin on the material, because I fear that knowing *anything* more about the nature of the life form will bring that precarious balance crashing down. I don’t want to know if the creature is conscious. I don’t want to know if the people who are the Thing know that they’re the Thing. I don’t want to know if David Keith was the Thing, or if MacReady was the Thing, or if they were both The Thing. That’s the Thing about the Thing–the more you know, the less it becomes.

Also, T2 is clearly inferior to the original. (*runs away*)

.

^

Nor do I want to know if the actor Keith David, who was actually in the movie, was the Thing.

Every time. I make that mistake every time. I’m so sorry Mr. David. I’m a big fan.

I’m a huge fan of movies / books where the author avoids explaining too much and just gets on with the damn story. Maybe that’s why I love that movie as much as I do. The short story it was made after tries to explain where the creature came from, its motivations, etc., and the result is spectacularly clunky and tedious to read. I’ll take the ambiguity any day.

An article I read a while back was comparing old special effects (puppets and ketchup, or whatever they used) to modern CGI, and The Thing was highly praised for its realism in this department.

Like with explanations, it comes down to preferences. CGI effects often look weird and unrealistic to me, like a poorly blended-in video game sequence happening somewhere behind he actual actors (even in some high-budget blockbusters). Annoying young whippersnappers laugh their asses off at Play-Doh and stop-motion animation.

I wasn’t really making a CG vs practical argument. Any level of tech can be employed well. It’s true that the Thing Pre-Make used cg effects, and that movie was dull and unnecessary. But that’s because the movie was dull and unnecessary–different effects technology wouldn’t have altered that. If it had used practical effects, it would have been a dull and unnecessary movie with practical effects.

This is why I cited examples of both good and bad effects driven scenes in the same movie. It’s not about the level of tech available, it’s about the directorial decisions to either make use of that tech from a position of its strengths or weaknesses. Dog Kennel scene great–mostly darkness, form and motion suggested with glistening highlights and those creepy filmed in reverse tendrils. Post-bloodtest scene–far over-reaching, effects allowed far too much scrutiny, action unconvincing, results in shattering suspension of disbelief. Because I’m on Team Thing, I’ve decided to find those sequences “fun”. If someone else wanted to claim them to be cartoonish and responsible for yanking them right out of the movie, though, I can totally see that.

It’s not that the effects look fake in those scenes. It’s that they look fake, behave ridiculously, and are not very artfully shot or edited. Those decisions are on Carpenter, and are a valid artistic critique of the film. Carpenter is at his best when he’s harvesting suspense, preferably with a heavy layer of deceptively simple moody synth on top. His weaknesses show whenever he veers into more visceral action style sequences.

Compare to say, Alien, which is not without its own rough edges. There are fleeting shots where the creature is clearly a statue being pulled on a dolly, or a guy in a suit, and I still always laugh at the newly hatched chestbuster rocketing away from the stunned group. Those shots, however, are precisely that–fleeting. The viewer is never given much time to dwell on them. Beyond that the creature in Alien is so much more than the practical effects–it’s the strobe lighting, the always present thumping of the heart like motion detector and rhythmic alarm klaxons. That movie is an absolute Laser-Floyd symphony of unbroken tension.

Alien is never less than an A movie–The Thing vacillates between being an A suspense thriller and a B horror movie. Even though I prefer the Thing because I find the premise more interesting, Alien is a better made movie, and better at being what it wants to be than the Thing, which requires me to make a lot of allowances for it. How the guy who made Alien managed to forget almost everything he knew about how to make that movie between it and Prometheus, is a mystery I’ll never solve.

The Thing is still probably my favorite movie. I’m no longer certain it’s a great movie, but it’s still pretty good. I’d still choose to watch it over any number of “better” movies, but that’s down to my personal preferences. If I’m choosing between a Scorsese pic and the Thing, I’ll pick the Thing every time, but I don’t harbor any illusions that it’s a better movie than Goodfellas.

I’m sure it’s just a fuckup on the part of the props department, but I’ve mock-seriously made the argument before that the history of Westworld starts before now—because, when Bernard goes down to essentially the catacombs and interfaces with “the old system”, the setup there would look outdated even a few years ago. So by that evidence, Westworld as a park must have been started no later than the mid-2010s…

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1CmDnGs5xeiCk9WlVPFfcInzWmYNdbbO_MTnRKdRf8Jc/edit?usp=sharing

I think that VGA cable may have actually been a DVI.

Not that that makes your case any less compelling…

Yeah, good point. I read it as consciously-ignorant anachronism– these designers-of-the-future decided their player-piano props should be playing antique music, and they’re far enough ahead of us that they didn’t really care whether that music was authentic or just old. ‘Course, that doesn’t address why they used old white-boy music. Being an old white boy myself, it didn’t even occur to me to notice until you pointed it out.

Yeah, just finished watching that myself. There’s eight hours of my life I’ll never get back.

On the plus side, they did pretty much nail the rivalry-between-academics element. Even if the writers don’t appear to have ever spoken to an actual research scientist before…

On the other hand, “The Thing” will never staledate because it’s explicitly set in 1982. “Alien” staledated the moment we came up with flatscreen video displays.

In the future, mock retro CRTs and chunky keyboards are all the rage! The magical artificial gravity of Nostromo’s future interferes with all LCD and/or holographic technology! Any interface tech more advanced than say, a Commodore 64, instantly explodes!

This is a separate discussion, though–unless you’re willing to go on record stating that Prometheus is a better movie than Alien because its human interface mock-ups are less dated.

[…] an an email exchange about it with the author Peter Watts, who blogged favorably about the show here. My email to […]

DA,

About that….

keithzg,

Visual storytelling, they struck a balance between obviously anachronic (CRTS?) and making the equipment look less futuristic. The whole premise falls apart when you start asking questions about VR anyway…

I also didn’t notice that aspect of the music choice until Stone Monkey’s comment. I like the show so tried to justify it in my head for a bit, but gave up when all I came up with was that it’s the type of music the show’s creators may like or that, demographically, the majority of the audience for the show may tend to like that type of music, both of which are explanations external to the narrative. But demographically this could also be the historical music of the future in the way Mozart, Stravinsky, Beethoven, etc., are “classical” music for us today. I’d have to look at the show again, but my recollection is that the majority of the guests are “white”. We don’t know much about what’s outside the park, but from the little we do know the outside world seems at least as nasty as today economically speaking, despite what guests to the park state about it (current day example: it’s true people generally don’t starve to death in Canada – does this mean everyone in Canada is well off? Two specific Canadians apparently have as much wealth as the bottom 30% of Canadians; those two might well feel comfortable stating that Canadians are well off, while some of us would define “well” differently than they do). I suspect the future will look increasingly like it does in the tv show “Incorporated” (or Richard Morgan’s Market Forces), with disenfranchisement playing out along a number of axes including “race”.

Wow. I disagreed with pretty much everything Peter Watts wrote in this blog post.

>> “So maybe it isn’t just sloppy writing. Maybe it’s significant somehow”

If you have to stoop this low, I think maybe somebody’s been hitting the Kool-Aid.

Or maybe it just shows how starved we are of good science fiction on the screen.

My apologies if this goes against the group think.

>> “In the future, mock retro CRTs and chunky keyboards are all the rage!”

The “staledating” issue with Alien is not just the screens. (For which they are obviously excused.) The whole ship and it’s interior doesn’t make much sense if you plausibly extrapolate technology so far into the future that we have a world like that. I mean they have steam coming out of pipes!? I always thought of it as a deliberate stylistic choice by the filmmakers. They knew full well that it wouldn’t look like that. It also handily makes things possible on a practical level in an era before advanced computer cgi and smaller budgets. Which is also why so often the monsters look humanoid: they have to fit an actor in there!

See also Twelve Monkeys and Brazil for more extreme examples of this, although those movies more deliberately go for an alternate history kind of thing.

Alien is one of my favorite movies. But let’s be honest: thematically or philosophically there’s not much going on; it’s basically a monster movie.

>> “How the guy who made Alien managed to forget almost everything he knew about how to make that movie between it and Prometheus, is a mystery I’ll never solve.”

Back then movies were still made by directors. Now they are made by committees and studio execs and marketeers who have to make sure a 16 year old kid in China will also appreciate the joke.

Speaking of those… might just be me, but has anyone else noticed similarities between the settings and storylines in Incorporated and MF? Like, significant similarities?

After watching the first couple episodes, I half-expected to see “based on the work of Richard Morgan” in the credits. Having followed a few alleged plagiarism “scandals” in recent years, I find this rather odd.

I’m nearly certain this exact conversation has happened before on the ‘Crawl, so I’ll try not to retread too much ground. Suffice to say that visual design is about communicating ideas, not practical reality. People understand at a glance the type of ship that the Nostromo is, and because the ship’s design uses recognizable familiar touchstones, people easily understand this to be a sort of industrial ship in space. Ironically, because the Nostromo is grounded in familiar reality of how we expect a giant industrial vessel to look, it feels *more* realistic than the Enterprise’s “Carpeted Living Room in space”, even though the latter is probably more speculatively valid.

To defend beleaguered visual designers everywhere who always catch nerd hell for design choices they make, they’re usually 3 steps ahead of their detractors, trying to balance practical functionality and aesthetic appeal with getting an idea across.They didn’t put that vulnerable cockpit on the top of that giant armored robot because they thought it was a practical thing to do–they did it because “Show, don’t tell” is the motto in any art, dramatic or otherwise. They want people to understand at a glance that the thing they’re looking at is a human controlled vehicle, not an automated machine.

Finally, just to frustrate the literal-minded further. Visual design in film is often more about how something makes you feel, than whether something passes intellectual muster. How does the visual design in Alien make you feel? You mentioned Brazil, and that’s a great example. It’s a more impressionistic film where visual reality is not necessarily meant to be taken literally. The giant typewriters and workfarms of that movie weren’t meant to speculative of a practical reality, but to evoke the feeling of being caught in bureaucratic labyrinth. The impractical machinery that Robert DeNiro pulls out of the wall aren’t meant to look functional, but to resemble the spilled organs of some giant beast.

Well, yes and no. It’s true that the themes in Alien never coalesce into obvious philosophical questions as in Blade Runner, but to say there’s nothing going on thematically is to say the same thing about Giger’s artwork. You can’t look at that guy’s stuff and think nothing is going on.

The themes in Alien are expertly deployed, but their purpose is more emotional than philosophical. Much has been written about the birth horror and sexual violation motifs in the movie. Again, it’s about how it makes you feel.

Alien may be a monster movie, but it’s an exceptionally crafted monster movie.

Fatman,

Not just you. The first episode appeared to me to be ripped right from the pages of Morgan’s book. The story lines have diverged since then, possibly in part because filming the road rage segments would have been too expensive, but the similarities at the start are striking.

Then again, as a vision of the future it seems likely enough in so many respects that perhaps no one can really lay claim to the vision, but only to specific story lines.