My Dinner with Ramez: or, The Identity Landscape.

A week or two ago— just before all the stuff with Kevin went down— I hung out with Ramez Naam for an evening. (If you know who I am you certainly know who he is; his Nexus trilogy burned across the charts in a way I can only dream of.) We snarfed. We drank. We covered all manner of topics from climate change to networked intelligence, from self-promotion to the Koch Brothers. It gave me the same kind of rush I used to take for granted in grad school; ideas and paradigms and competing hypotheses dueling over beers, a kind of good-natured head-butting where ideas trump ideology. I also have Mez to thank for kicking loose in my brain perhaps the first semi-original idea I’ve had in months.

It has to do with continuity of the self.

We all know that the mere act of existing changes us. Every poster you read, every song you hear, every fart you smell rewires the brain a little. Every perception of every qualium literally changes your mind.

How many of those changes does it take to turn you into a qualitatively different person?

It’s a question that’s always nagged at me. I certainly feel like I’m the same person I was when I was eighteen— my tastes may have changed, I may have learned a bit more restraint, my priorities and opinions may have mutated and metastasized— but that all just feels like tweaking the interface. Swapping out old peripherals for new. Deep in my skull the CPU feels the same it always has, even if it’s layered a few more social skills onto the GUI. All my experiences, such as they are, don’t seem to have altered my basic perceptions and attitudes very much. To the extent that I’ve been reprogrammed, those inputs haven’t reprogrammed me as much as, say, a tamping iron through the frontal lobe. Or even the less-traumatic— but no less remarkable— messianism that sometimes results from epilepsy.

From split-brain studies to multicore manifestations, there seem to be cases in which one person can abruptly change into another. Is this truly a more radical transformation than the changes we all go through in the course of our lives, or does it simply seem that way because it happens instantaneously? How much of a difference is enough? How many arguments and antiabortion posters and life-threatening situations do you have to experience before you’ve turned into someone else, a different being lurking behind the same name and face?

It may seem like a fatuous question, like arguing over a series of indistinguishably different shades of paint; a biologist friend of mine likened it to trying to define the term species (how many genetic differences are enough? How many incompatible traits?). Maybe it’s a fool’s errand to try and make a step function out of something that’s intrinsically continuous— and yet, dammit, there are these radical toggle-shifts between personae, even as there are innumerable little edits and rewires that alter a stable identity from second to second. Kevin can switch from relative lucidity to literally thinking that he and his cat are the only non-illusory beings in the universe, and that they are living on the surface of the Sun. Surely there’s got to be a model that encompasses both?

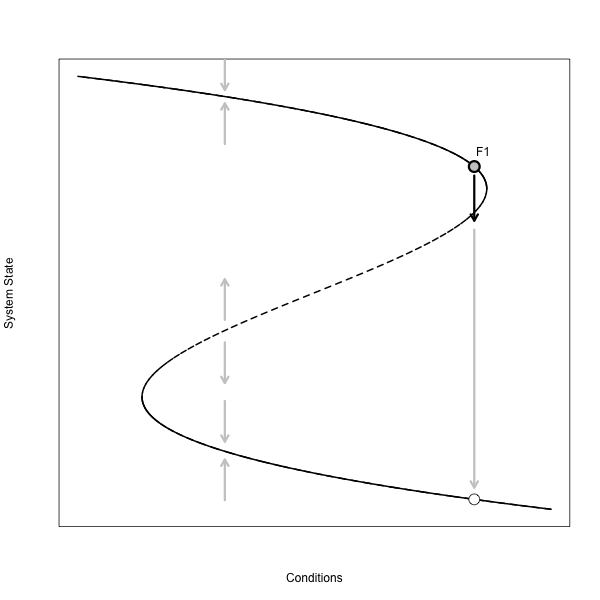

The question came up while Ramez and I were talking about uploaded consciousness— something to do with how much fidelity the upload has to share with the meat in order to be considered the same individual— and faded again into the last round as the subject turned to climate change. Ramez is intrinsically more optimistic than I about our prospects in that regard (although not so optimistic as his twitter feed might lead you to believe); I was trying to change his mind by reconstructing what I remembered from grad school about fold catastrophes:

It’s like all the possible system states form this line, I said. Imagine that the system itself is a ball bearing rolling along it. A fold catastrophe is what happens when the line twists into a kind of overhang. The system is perfectly stable until it reaches the edge of that cliff; then it drops down to a whole new equilibrium. It only took a little push in one direction to go over the edge, but you can’t get back to your original state by simply expending the same amount of energy in the opposite direction; it takes way more energy to get back up the cliff than it did to fall off it in the first place. So the system stabilizes at a new, lower, more fucked-up equilibrium, and it’s pretty much stuck there.

We were talking about climate change, but the residue of our previous foray into neuroscience was still rattling around in my mind. And over our third beers, there at the Bedford Academy, those two subjects just kinda clicked, two bubbles in a Venn Diagram overlapping at just the right spot—

What if Identity is like a fitness landscape?

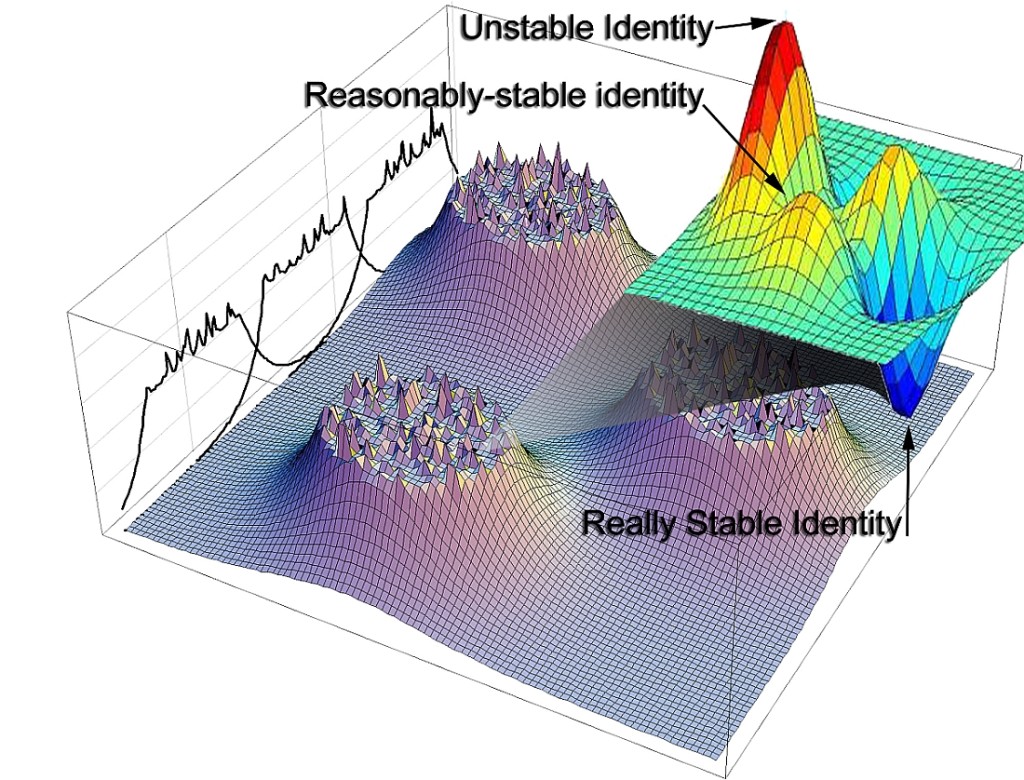

Forget the simplistic 2D line I invoked for fold catastrophes; that’s just one axis of a complex system. And forget any N-dimensional landscape that could hope to encompass fitness landscapes in all their glory; our dumb ape brains wouldn’t be able to grasp those figures even if there was some way of rendering them on the screen. Settle instead for a 3D surface where fitness scales to altitude and the X and Y axes represent any two variables you’d care to consider. Grab that ball-bearing from the previous exercise; once again, that represents the actual system at any given time.

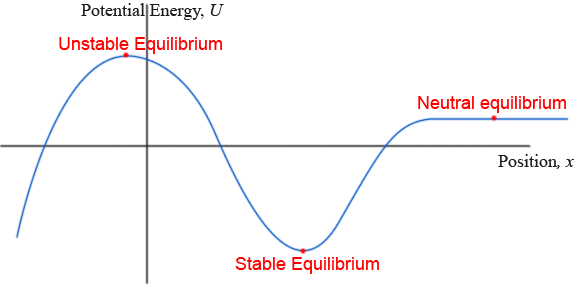

There are a lot of equilibria on such landscapes, places where the ball-bearing— left to itself— would rest motionless forever. Some of them are stable: little pockets in the landscape the system will roll back to even if perturbed. Once achieved, it takes a lot to keep it away from those coordinates. Other equilibria are unstable. Think of the ball-bearing balancing atop a peak: it won’t move if you don’t disturb it, but you could knock the little fucker from its perch with a sneeze— and once displaced, it’s unlikely to ever attain those heights again. And then you’ve got the neutral equilibria: the flat bits, where the system can be pushed off-center with relatively little force but can be pushed back again just as easily.

There are a lot of equilibria on such landscapes, places where the ball-bearing— left to itself— would rest motionless forever. Some of them are stable: little pockets in the landscape the system will roll back to even if perturbed. Once achieved, it takes a lot to keep it away from those coordinates. Other equilibria are unstable. Think of the ball-bearing balancing atop a peak: it won’t move if you don’t disturb it, but you could knock the little fucker from its perch with a sneeze— and once displaced, it’s unlikely to ever attain those heights again. And then you’ve got the neutral equilibria: the flat bits, where the system can be pushed off-center with relatively little force but can be pushed back again just as easily.

Everything else on the landscape is slope, transition zone. The system can pass through those states, but always on its way somewhere else. It can never come to rest there.

Just sign off on the concept, and we’ll fill in all the fiddly little details later. Graphic grabbed from Hayashi et al 2006, stapled together with some other stuff, and and put to completely inappropriate use in a totally different context.

You see where I’m going with this, right? You saw it about three paragraphs ago. I’m not talking about landscapes of genetic or ecological fitness at all; I’m talking about neurological system states.

Every equilibrium is a Self, an identity. The slopes between them contain camping trips, love affairs, concerts— all the day-to-day experiences that incrementally change the system as it moves through phase space, but not enough to change the identity at its heart. No one of these infinite-divisible coordinate shifts is enough to turn one Self into another; for that, you have to move between equilibria. At the same time, you can’t move from one equilibrium to another without passing through a myriad of those intermediate states.

The vital variable, therefore, is how steep the slope is between selves.

The Sybils and Phineas Gages and Kevins of the world, rolling around their steep hills and valleys, may go through more transitional states in minutes than the average neurotypical would experience in decades, maybe a whole adult life. The trip covers the same straight-line distance; its just that most of that distance is measured vertically, along the Z axis. People with a secure, stable sense of self will exist in topographic depressions, stable equilibria the ball-bearing will roll back to after all but the strongest perturbations. People on the verge of a psychotic break might be perched atop a mountain somewhere.

(For the purposes of this post it doesn’t really matter what the axes measure—any relevant metrics of brain activity will do— since any useful quantitative model is likely to have way more than three dimensions anyway. This is just an illustration of the general principle.)

It’s not a perfect model. What about the plains, for example, the realm of the neutral equilibria? If you define each Self as an equilibrium, then the plains would contain myriad Selves existing cheek-to-jowl, technically separate “people” even though they may only differ in whether they think that “Spock’s Brain” was a worse episode than “Plato’s Stepchildren”. On the flatlands, you could change back and forth from one person to another a dozen times during the course of a single Star Trek episode. This doesn’t leave us much better off than we were before.

Offhand I can think of two ways to deal with this: either exclude 0-slope terrain from the model as a starting condition (thus eliminating neutral equilibria); or weight the value of the Z-axis in such a way that the separation in the X-Y plane doesn’t matter nearly as much as separation in altitude. In the latter case, the system could change from one self to another either by moving halfway across the world horizontally (the equivalent of gradually becoming a different person as you accumulate experience throughout your life); or by only moving a step or two the left in XY space while moving radically along the Z axis (those identities that shift instantly, those cases where it seems as though there are two people in the same head).

I don’t know. Maybe it’s just a useful metaphor (then again, ecological fitness landscapes are basically metaphors anyway); maybe it’s a framework for something you could plug real numbers into. Or maybe it’s just a deep dumb dive down a wrong alley. But I’ve been thinking about such things ever since Kevin arrived, and vanished, and reappeared like a scarecrow in our back yard (yeah, the story continues— another post, maybe). And I can’t help but think that this insight, right or wrong, would never have occurred to me as I sat here typing and scrolling and reading by myself with my cats at my side; it took a free-wheeling conversation with a dude I’d just met for me to knock those pieces together in new ways. I’ve lost count of the cool ideas that have emerged not from my brain, not from someone else’s, but from the sparks that fly when two or more brains get together in meatspace and real time. I’ve yet to experience an online platform that works as well as the neighborhood pub.

It’s a bit ironic, though, isn’t it?

Almost two thousand words of free-wheeling cognitive speculation, of new conceptual models of neuroidentity— and it all boils down to the conclusion that I need to go out more often to kill my own brain cells.

This is nice, because it pushes out new ideas way faster than I have time to write them down. N-space (three is not enough), directional field effects (because farts and pop songs have completely different n-space vectors of effectiveness), orthogonal movements (some things only affect you one way), projections of movement in the n-th dimension on the other n-1 dimensions (because some things that only affect you one way show up on the other measures anyway), static yet complex fields (bumped off your hill, partway down, the n-space direction of ‘down’ may change). It feels like it has the complexity to handle modeling the complexity of fitness landscapes, although that might still leave it too complex for us to effectively model in any useful way. That shouldn’t stop us from trying!

There are actually people exploring something aspects of this problem. E.g., you might find this interesting: http://nonsymbolic.org/PNSE-Summary-2013.pdf

It’s not directly on-topic, but it talks a bit about how the brain’s state of operation can flop over and stay flopped over. In addition to the states the author describes, there are also similar states with negative affect. But they seem to generally have the exact property you describe: once in one of these states, it’s quite a lot of work to get out of them.

Personally, I feel like a *much* different person than I did in my 20s–though perhaps that’s wishful thinking because that guy was kind of a douche. I just find it really unfair that I have to share so many legal documents with that guy, and that he was able to make so many decisions that I’m forced to live with. It would be nice to be able to periodically get yourself certified with new personhood.

Almost certainly wishful thinking. As much as every experience changes us, the experiences in those first 20-27 years (last I read, meaningful cognitive development was still taking place even into the late 20s) are weighted far more heavily, forming the basics for patterns of behavior you’ll repeat your entire life. I’m pretty much always going to be working against the instincts of that same 20 something asshole, even though I’m twice his age and value very different hings now.

Edward (edwardlib.org) is essentially Stan for TensorFlow. That is, an implementation of Hamiltonian Monte Carlo and a few related techniques that is applicable not just to relatively simple Bayesian statistical models but to deep neural networks. Hamiltonian Monte Carlo is a much more efficient algorithm than previous methods such as Gibbs sampling at exploring the belief space. I’m not sure it’s hugely better at escaping local optima, but in higher dimensions meta-stable states are also important (as Chris S was talking about), and it should be much better at navigating these. Anyway, we are close to the point where what you are talking about stops being a metaphor and starts being something we can computationally model in systems that are recognizably intelligent.

DA, perhaps that, and neuroplasticity can be explained in this metaphor, too. If the fitness landscape looks more like a fractally generated landscape map, then for every local minima you have larger minima containing it, like alpine lakes scattered up the slope of a mountain range.

Assume that for neurotypical people, the walls get steeper as you age. While you’re a child, you can move all over the map fueled by plasticity and hormones. Eventually it gets harder to hop out, and you can only move between a few neighboring large valleys. Then at a certain point, you lose the ability to hop out of your valley without a concerted effort, and you’re just bounding around between mental alpine lakes and craters of stability.

@Andrew

Seems simpler to just say I’m an asshole. I respect your metaphor crafting though!

Nice metaphor.

Have you read Greg Egan’s Schild’s Ladder? It contains another neat use of the geometry of surfaces to model the change of psychological identities; this metaphor even gives the novel its title. Consider a tangent vector attached at some point A of the surface of a sphere. Now move the vector v along some path on the sphere towards a second point, B, taking care to keep it tangent to the surface but otherwise not “forcing” it to change direction — thus performing what is called “parallel transport” of tangent vectors. At the point B, you’ll end up with some other tangent vector w. The point here is that the new vector w depends not only on the initial vector v but also on the path it has taken: if you move v to the same point but following a different path on the sphere, in general you will end up at B with a different vector w’. This is a fact of differential geometry.

See where this is going? In the novel’s universe, people live for tens of thousands of years, journeying around the galaxy by beaming out copies of their brain-states.

Egan uses parallel transport as a metaphor for how an individual’s identity evolves through their life’s long journey: more specifically, if somebody (v) beams out two identical copies of their own brain which then go on living distinct lives for thousand of years (the two different paths), and if one day the two copies were eventually to meet again (at the point B), it would be a meeting of two completely different individuals (w≠w’).

for our edification, and not to detract from your nice metaphor , let me point out (via quote) that:

“[…] our intuition about local minima/maxima is wrong in extremely high dimensional spaces. In two and three dimensions, local minima/maxima are common. In a million dimensions, local minima/maxima are rare. The intuitive explanation is that for a local minimum/maximum to exist, the function must be curving up/down (first derivative = 0, second derivative >= 0 [<= 0] ) simultaneously in every dimension. It makes sense that as you add more dimensions this becomes less and less likely, and for a million dimensions it's vanishingly unlikely.

What you get instead of local minima [or maxima] are saddle points, where some dimensions are curving up and some are curving down."

[from ycombinator slash item?id=10678121]

(even for just 10 dimensions, assuming random signs for second derivatives, the probability of all 10 having the same sign is only 2/2^10 = 0.002)

Never heard of your friend so this means you’re more famous as far as I’m concerned 😉

I’ve often thought 40 years could be considered analogous to a bullet, no one emerges the same after taking it on the head.

On the other hand I’ve also said being an adult beyond your 20s is nice in that it gives you a bit of an extended timeframe in which you’ve basically been the same person for the last 10-15 years, which can’t be said of early tweens.

I’ve been trying to come up with examples of well done gradual personality changes in fiction, and I think one of the best examples is the webcomic zebra girl in which the protagonist is turned into a demon. It’s been going on for almost 20 years so I guess there’s a reason it’s so development is so organically gradual.

Try Stoner by John Williams. Exquisite development of multiple characters over a lifetime. Wonderful writing and a very touching read. Literature at it finest IMO.

I think this idea has enough legs that you could run with it in fiction. Assuming we can model personality changes like this, you could imagine a future form of therapy for someone like Kevin; you perhaps can’t eliminate the bad states, and you can’t eliminate transition into them, but perhaps you can ease transition through the whole subspace of bad states so you don’t get *stuck* in them. So you might be in a good state for a few hours to a week, but when you venture into a bad state you careen around through 7 types of mental hell for 15 minutes then you’re in a more stable good state.

Now that I’ve written that, it’s getting close to what Bear talked about in “Queen of Angels” with special therapy techniques and even “Selectors” who punish people by trapping them in terrible mental states – might need to re-read that one.

I really hope you can get beer with Bear and tell us what you talk about.

I’m probably completely missing the point here (this, for me, tends to be a really stable identity), but I find a distinction between first person and third person views when discussing “selfs” to be helpful. From the outside, I’m sure I’ve appeared to be many different people over time (both to different people, and also to any one particular person who’s been around me for a while), but from my own perspective I’m the same person, sometimes comfortable in my body and brain, and sometimes not, but always the same person riding this sack of meat. I believe Phineas Gage, all appearances to the contrary, was also the same person. This doesn’t preclude my taking a third person objectivating stance to my own personality, it’s just an attempt to make a distinction between my own meat-driven personalities and my sense of being conscious.

As a model explaining rapid and extreme changes in the way an individual appears to us to apprehend our world, it seems to fit very well, and requires far less of a leap than positing a Boltzmann brain…

And if Kevin is back living rough, I hope it’s his choice, and not just because TCHC is being a dick (I realize that the two are not mutually exclusive).

I would say don’t confuse the camera for the camera operator. Your perspective as the meat-rider is always the same, but the person who gets into that driver seat every day changes over time, sometimes drastically.

My experience is almost the opposite from yours. Other people are really bad at recognizing the ways you’ve changed as a person, especially if they see you all the time and the changes are gradual. This is evident in self righteous public shamers who would be willing to forgive things in themselves they wont forgive in public figures who may have committed some questionable acts as a younger person, as well as in friends you haven’t seen in a while that still expect you to conform to their idea of you, even though they themselves have changed.

“Hey DA, remember that time you took a dump in our barbecue?” Well, kind of. I remember the collection of cells running around with my name at the time doing it, but the thought process that lead to it is completely alien now. There’s no part of me that thinks that’s a good idea, and I can’t remember why I ever did.

It’s not always a positive gain, either. Whoever was running around in my body in its 20s also had a lot of positive habits I can’t replicate. They really cared about tennis and would condition for 2 hours a day. I can’t imagine caring about anything enough to exercise for two hours a day–even though it drastically changes the way I experience the world physically, which colors all my new experiences differently as well.

I’m all for some sort of way to quantify this. I would love to be able to see if I qualify for entirely new personhood under Dr. Watt’s model, or if I really am just the same old asshole with less hair and muscle tone. Could I then petition to have my memories expunged so as not to be burdened by the acts of another person? Or are memories central to our identity, and would changing them result in an entirely new person yet again?

There are times when I look back at who I was in my 20s and feel like a totally different person. But then the meat-sack that is me comes under some kind of outside stress and I get defensive and react badly and I realize how little has changed.

I’ll have to reread that whole post – too many good ideas, and I scanned it on my phone. It looks better on my computer.

BTW I read the Naam trilogy – loaded with good ideas, but your fiction gives me chills and his doesn’t. Your work really creeps me out. Can’t wait for your next book!

I think there’s a unity between your character development and your plot development that works in a way Naam’s does not. Naam, despite his mind-blowing technologies, incorporates his technologies into the human realm, and your work points beyond the human in an ego-hurting way. Your work makes me kind of feel that Homo sapiens is on a road that goes nowhere, at least no path that the conscious self can tread.

Keep writing!

Roy Verges,

“work points beyond the human”

He’s one of the only writers I’ve read who I find does this convincingly.

DA,

I’m not clear on your distinction when you write: “Your perspective as the meat-rider is always the same, but the person who gets into that driver seat every day changes over time, sometimes drastically.”

The “person” who gets into the driver seat is not, in my view, a person. The electrochemical impulses driving it have been predetermined by my life experiences and my genes (some of which have been activated by my life experiences, and some of which have not). I don’t feel or believe that my sense of being and will is without efficacy, but that’s a different matter that raises the question of how sentience arises (or, where it comes from).

If you feel like you are not the same person you were years ago, perhaps you aren’t. Perhaps the Boltzmann brain hypothesis applies. Or perhaps different humans work differently. Perhaps Bertrand Russell’s criticism of Decartes’ “I” is both valid and not – perhaps Russell really was a different person from moment to moment while Descartes’ being was continuous.

I think the people who see you in the same light they did from back in the day (and I’ve experienced that) are simply captive to their own preconceptions. If they were able to observe you as a character in a movie, I’d guess they’d see change. Albeit, even if they couldn’t, if the change wasn’t visible, it doesn’t mean that you haven’t changed internally, even if you don’t act differently and don’t have the will to do so but wish you could act differently. That would presumably still show up as a change in neurological topology. To the extent this is true of me, though (changes in who I wish I was from the young me to the me now, but that I haven’t been able to put into effect), I don’t see myself as being a different person. I guess at heart I’m analogue, not digital.

If I had no memories (addressing your last point), if I lost the ability to remember short term (I know someone like this, Memento like, but elderly), and long term (Alzheimer’s-like I guess), and lost my non-declarative memory (so I couldn’t remember how to type, or walk, or eat), I don’t know if I’d still be there somewhere, but I’m afraid I might be. We’re here. I don’t know if there’s a way out. (Hamlet, and Sophocles’ observation that “to never have been born may be the greatest boon of all”, may apply here…)

[…] Watts considers the question of individual identity over time. What changes, what stays the […]

Cool.

Interesting how they specify “nondual awareness” up front. As though that weren’t the default…

Now isn’t that a cool premise for a story. If you can prove that your Identity Landscape has changed past a certain point, you are considered a different individual and can no longer be held responsible for acts committed by a different landscape in the same brain.

Call it “Statute of Liimtations”…

hat part I can understand just fine. I think the rest of your comment is gonna have to wait until I can read it with Wikipedia and Google open at my side…

I have read maybe three Egan short stories, and none of his novels. This shames me every time the subject comes up.

Awww. I was having so much fun, too. Thanks a lot.

OK, wait: let’s say we keep the dimensionality low by plotting not specific variables, but principle components. So you retain some measure of multivariate complexity without having to deal wit those fucking saddles.

Your move, Killjoy…

Way ahead of you. See previous comment.

You mean Greg or Elisabeth (aka, Ursabelle)? ‘Cause I used to hang out with Ursabelle semiregularly, until I was banned from her country and she refused to emigrate.

I think that might be an artifact of experiential continuity; just as Metzinger (and others) argue that the “self” is an illusion, maybe the “stable self” is too: the brain perceives an unbroken string of experiences from the same viewpoint and concludes that the viewer has been constant. Whereas, it’s possible that the peripherals stayed the same (hence continuity of perception) but someone swapped out the motherboard.

For me, it was lurking in the middle of a one-lane bridge over a chasm in my parents’ car in the middle of the night, lights turned off, waiting for my drunken friends coming home from the party to drive up behind me— at which point I’d turn the lights on and floor the vehicle in reverse, heading for their grill at 30mph.

Honestly, sometimes I don’t know how I lived long enough to nearly die from flesh-eating disease.

I was speaking figuratively. Just trying to separate hardware from software. The sense of self always has the same perspective–you’re always going to the “driver” looking out from behind your eyes, inhabiting your body. In that respect, you will always feel the same. But the actual “driver” calling the shots changes over time so gradually, it can be tough to see how far one may (or may not) have come.

Can’t speak for everyone, of course, but I have very different thought processes and priorities than I did 20-25 years ago. I suffered a lot–mostly self-inflicted–but this significantly increased my capacity for empathy. I read more widely and try to stay informed on a variety of subjects. My political and philosophical viewpoints shifted drastically. I value personal relationships more. I do not feel like the same person I was, and that person’s thought processes seem alien to me now. I would not be capable of making many of the decisions I once did.

To confuse matters though, I also share a lot of the same traits and flaws with that person for better and worse. A lot of those are probably embedded in the hardware. I still make some of the same mistakes, but not all of them, and some are entirely new.

Obviously I don’t much like the person I used to be, so Dr. Watt’s model has a lot of appeal. I’d love to think I’m different enough to qualify as a different person. I’m probably the same asshole, but I’d love to be able to score it somehow. Maybe I could slip in just under the threshold.

In the interests of full disclosure, that specific example I gave was fiction. I’m guilty of similar and worse acts though.

Wow! Stunning idea for a story! Who would do the certifying? A government agency? If so, who would they hire? On what bonafides? Social workers? PhD’s in Psychology? Psychiatry? Pharmacology? Perhaps some combination of Computer Science, Math and the disciplines.

Think of the power these groups would have. Then, this whole political structure could be hacked, or attacked by Congress with less funding over successive years. Then, less and less qualified people could be substituted for the originators of the program.

If hacked, how would a false personhood certificate be used?

If a trusted certificate for everyday use, how would that affect getting a job? Or dating?

Could the same machines that measure personhood be used to instill a different personality?

And so forth. Didn’t sleep much last night…

Perhaps the inner life could be described as a journey through the fitness landscape. In a psychologically healthy person, who avoided extreme trauma, illness, injury, and who had a conventional life with family and friends (trying to limit the variables here), then daily experience could guide the mind through various states, to be encoded during sleep as a pathway to the next day’s fitness landscape?

Probably too vague to be useful. Oh well.

DIY Personality Hack – a kit you could buy for $399.99. Amuse yourself and your friends! Set it up in your garage! Turn yourself from an expressionist painter into a day trader in minutes!

Some dreary government office I suppose, like the DMV. Face your lobes towards the scanner and take an unflattering neuro-topographical image. If you pass the variance threshold, fill out a form, pay the identity transfer fee and boom–you’re a brand new asshole as far as the state is concerned. Periodic renewals required every 5 years to check for personality drift.

Obviously it has criminal justice applications. Imagine if someone discovered a horrible crime I was guilty of decades ago, but I had since transitioned to new personhood. Would they edit my brain to restore my earlier self in order to sentence that identity? For someone like me who doesn’t much like their previous selves, would I be forced to become a fugitive in order to run from myself?

Anyway, this is all pretty well trodden territory in science fiction as far as I can determine, at least as a background element. Editing personalities as a “humane” alternative to incarceration or execution is certainly well covered. Blindsight touches on it as well in the section with Siri and his girlfriend:

Peter Watts, just as Metzinger (and others) argue that the “self” is an illusion, maybe the “stable self” is too

I’m going to have to read Metzinger (beyond Wikipedia!). Logically, the idea that there is no “self” makes sense to me, but, just as parallel universes theories, while providing a way to understand some of the implications of quantum mechanics, don’t explain why we only feel ourselves to be in only one of those universes, I find the idea that my sense of self is an illusion to be cold comfort while navigating this world. That said, I’m agnostic on all of this, and will need to read Metzinger (and others) to test that agnosticism!

Ivo,

I seem to recall Schild’s ladder being about preservation of relationships. So two people who were friends as children may be friends as adults, even though they are quite different people at different times, if they have gone through roughly the same experiences. The culture of the book was very conservative, and went to great pains to ensure this sort of continuity of relationships, until (this is Greg Egan) the universe was destroyed and replaced by something bizarre and inexplicable.

Reminiscent of the analogy-by-parallelogram that is possible in word embeddings, eg girl-boy=woman-man.

“You’re not even close to baseline.”

Obviously, if you could read the mind with such precision that you could find crimes, then it’d be trivially easy to use some sort of invasive method to restructure the personality to make re-offending unlikely.

@Peter Watts

Neat bit of thinking here, but given that we’re not brains-in-a-vat, of limited use. The environment one is in affects everything. Personality is the sieve, environment is the water pouring through it. Who we are depends on where and when we are.

Everyone imagines they’re a good person who’d never do a ‘thing like that’, but we all know how the Germans or Japanese behaved in WWII.(1) In the right environment, 99% can be reliably made to act in a murderous manner, and given your authorial tendencies I really don’t think you’d be the saintly 1%…

The real trick, just like with staying safe, is not to get exposed to the wrong circumstances.

(1) Or Americans. Official histories don’t mention it, but private diaries and personal accounts make it clear that shooting POWs was a fairly common thing. There were even soldiers who were known for dodging escort duty by going just a bit away from their unit and then shooting the POWs they were supposed to escort. Given that German orders were “give up only after you run out of ammo”. Americans were rarely moved by such laziness…

You made me go back to the book and check… I think we’re both right. Schild’s ladder and parallel transport are used both as a metaphor for the preservation of individuality and of relationships. They come up in a conversation between nine-year-old Tchicaya and his father. As his birthday approaches, Tchicaya says he doesn’t want to grow old and change. His father, mistaking this for fear of death, reassures him that he “will outlive the stars, if he wants to”. He answers: “But if I do… how will I know that I’m still me?” So Tchicaya’s father employs advanced differential geometry (what else!) to explain to his son how his identity can be transported step-by-step, somehow without change, throughout one’s life. From the book: “Tchicaya didn’t ask if the prescription could be extended beyond physics; as an answer to his fears, it was only a metaphor. But it was a metaphor filled with hope. Even as he changed, he could watch himself closely and judge wether he was skewing the arrow of his self.”

Then the father makes a second point about relationships: different paths between the same two points yield different outcomes, but as long as two people travel through (roughly) the same path, their end-point selves will stay close. He concludes: “There’s nothing to be afraid of. You’ll never be a stranger if you stay here with your family and friends. As long as we climb side by side, we’ll all change together.”

But then, of course, Tchicaya leaves his family and friends to travel the galaxy for a few thousand years…

Peter Watts,

I find Greg Egan’s novels are even better than his short stories, so you should do yourself a favour and read them! My personal favourites are Schild’s Ladder and Diaspora, which should appeal to you with their subtle balance between the existential despair induced by the cold indifferent universe and a persistent humanistic hope in the capacity of intelligent life to adapt to it and find reasons to keep going.

So we’re talking bots creating and naming videos based on popularity of other videos and it appears to work…on young children. Titles are word salad popular hashtag/search terms. Something head-cheesey about all this.

Something is wrong with the Internet.

Yeah, I saw that. Not so much Head-cheesy as Anemoneish. But, yeah. The meltdown Madonna meme got started in pretty much the same way.

I can only hope that by 2050 they’ve got better graphics.

FS,

Brains are time crystals you say? Could be one of the keys to our generality that we might not ever reach a true equilibrium.

http://news.berkeley.edu/2017/01/26/scientists-unveil-new-form-of-matter-time-crystals/