Denying Dystopia: The Hope Police in Fact and Fiction

I recently read Terri Favro’s upcoming book on the history and future of robotics, sent to me by a publisher hungry for blurbs. It’s a fun read— I had no trouble obliging them— but I couldn’t avoid an almost oppressive sense of— well, of optimism hanging over the whole thing. Favro states outright, for example, that she’s decided to love the Internet of Things; those who eye it with suspicion she compares to old fogies who stick with their clunky coal-burning furnace and knob-and-tube wiring as the rest of the world moves into a bright sunny future. She praises algorithms that analyze your behavior and autonomously order retail goods on your behalf, just in case you’re not consuming enough on your own: “We’ll be giving up our privacy, but gaining the surprise and delight that comes with something new always waiting for us at the door” she gushes (sliding past the surprise and delight we’ll feel when our Visa bill loads up with purchases we never made). “How many of us can resist the lure of the new?” Favro does pay lip service to the potential hackability of this Internet of Things— concedes that her networked fridge might be compromised, for example— but goes on to say “…to do what, exactly? Replace my lactose-free low-fat milk with table cream? Sabotage my diet by substituting chocolate for rapini?”

Maybe, yeah. Or maybe your insurance company might come snooping around in the hopes your eating habits might give them an excuse to reject that claim for medical treatments you might have avoided if you’d “lived more responsibly”. Maybe some botnet will talk your fridge and a million others into cranking up their internal temperatures to 20ºC during the day, then bringing them all back down to a nice innocuous 5º just before you get home from work. (Salmonella in just a few percent of those affected could overwhelm hospitals and take out our medical response capacity overnight.) And while Favro at least admits to the danger of Evil Russian Hackers, she never once mentions that our own governments will in all likelihood be rooting around in our fridges and TVs and smart bulbs, cruising the Internet Of Things while whistling that perennial favorite If You Got Nothin’ to Hide You Got Nothin’ to Fear…

Nor should we forget that old chestnut from Blue Lives Murder: “I had to shoot him, Your Honor. I feared for my life. It’s true the suspect was unarmed at the time, but he’s well over six feet tall and according to his Samsung Health app he lifted weights and ran 20K three times a week…”

That’s just a few ways your wired appliances can hurt you personally. We haven’t scratched the potential damage to wider targets. What’s to stop them from getting conscripted into an appliance-based botnet like, for example, the one that took out KrebsOnSecurity last year?

I’m not trying to shit on Favro; as I said, I enjoyed the book. But it did get me thinking about bigger pictures, and this recent demand for brighter prognoses. These days it seems as if everyone and their dog is demanding we stick our fingers in our ears, squeeze our eyes tight shut, and whistle a happy tune while the mountainside collapses on top of us.

In a sense this is nothing new. Denial is a ubiquitous part of human nature. One of the things science fiction has traditionally done has been get in our faces, hold our eyelids open and force us to look at the road ahead. That’s a big reason I was drawn to the field in the first place.

So how come some of the most strident demands to Lighten the Hell Up are coming from inside science fiction itself?

*

It started slow. Remember back at the beginning of the decade, when the president of Arizona State University told Neal Stephenson that the sorry state of the space program was our fault? Science fiction wasn’t bold and optimistic like it used to be, apparently. It had stopped Dreaming Big. The rocket scientists weren’t inspired because we weren’t being sufficiently inspirational.

I’ve always found that argument a bit tenuous, but Stephenson took it to heart. Booted up “Project Hieroglyph“, a big shiny movement devoted to chasing dystopia down into the cellar and replacing it with upbeat, optimistic science fiction that could Change The World. The fruit of that labor was Hieroglyph: Stories and Visions for a Better Future; a number of my friends can be found within its pages, although for some reason I was not approached for a contribution. (No problem— I got my shot just this year when Kathryn Cramer, the coeditor of H:SaVfaBF, let me write my own piece of optiskif for the X-Prize’s Seat 14C.)

A few grumbled (Ramez Naam struck back in Slate in defense of dystopias). Others dug in their heels: You don’t need to squint very hard to figure out Michal Solana’s take-home message in “Stop Writing Dystopian Fiction – It’s Making Us All Fear Technology“. That appeared in Wired back in 2014, but the bandwagon rolls on still. Just this year, writing in Clarkesworld, my dear friend Kelly Robson put her foot down: “No more dystopias [italics hers]. What we need is near- and mid-future stories that show an array of trajectories out of the gloomy toilet bowl we’re spiraling.”

There’s something telling about that edict, insofar as it explicitly admits that yes, we are indeed circling the drain. We’re all on that same page, at least. But what the hope police[1] seem to be converging on is, You don’t get to give us bad news unless you can also tell us how to make it good. Don’t you dare deliver a diagnosis of cancer unless you’ve got a cure stashed up your sleeve, because otherwise you’re just being a downer.

Looks like dangerous seas up ahead. I know! Let’s erase all the reefs from our nautical charts![2]

*

Inherent in this attitude is the belief that science fiction matters, that it can influence the trajectory of real life, that We Have The Power To Change the Future and With Great Power Goes Great Responsibility— so if we serve up an unending diet of crushing dystopias people will lose all hope, melt into whimpering puddles of flop sweat, and grow too paralyzed to fix anything. Because the World takes us so very seriously. Because if we do not tell tales of hope, then we have no one to blame but ourselves when the ceiling crashes in.

I’ve always been a bit gobsmacked by the arrogance of that view.

I’m not saying that SF has never proven inspirational in real life. NASA is infested with scientists and engineers who were weaned on Star Trek. Gibson informed the future as much as he imagined it. Hell, we wouldn’t have the glorious legacy of Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative if a bunch of Real SF Writers hadn’t snuck into the White House and inspired the Gipper with hi-tech tales of space-based missile shields and ion cannons. I’m not denying any of that.

What I’m saying is that none of those things inspired people to change. It merely justified their inclination to keep on doing what they’d always wanted to. Science fiction is like the Bible that way: it’s big enough, and messy enough, to let you cherry-pick “inspiration” for pretty much any paradigm that turns your crank. Hell, you can even use SF to justify a society based on incest (check out the works of Theodore Sturgeon if you don’t believe me). That’s one of the reasons I like the genre; you can go anywhere.

You want to convince me that SF can change the world? Show me the timeline where we headed off overpopulation because people read Stand on Zanzibar. Show me a world where the existence of Nineteen Eighty-Four prevented the US and Britain from routinely surveilling their citizens. Show me a place where ‘Murrica read The Handmaid’s Tale and whispered in horrified tones: “Holy shit, we really gotta dial back our religious fundamentalism.”

It’s no accomplishment to inspire people to do things they already want to. You want to lay claim to being part of Team Worldchanger, show me a time when you inspired people to do something they didn’t want to. Show me a time you changed society’s mind.

Ray Bradbury tried to imagine such a world, once— late in his career when he’d gone soft, when hard-edged masterpieces like “Skeleton” and “The Small Assassin” were lost to history and all he had left in him were mushy stories about Laurel and Hardy, or time-travelers who used their technology to go back and make Herman Melville feel better about his writing career. This particular story was called “The Toynbee Convector”, and it was about a guy who saved the world by lying to it. He told everyone that he’d built a time machine, gone into the Future, and seen that It Was Good: we’d cleaned up the planet, saved the whales, eliminated poverty and overpopulation. And in this upbeat science fiction story, people didn’t say Great: well, since we know everything’s gonna be okay anyhow, we might as well keep sitting on our asses, snarfing pork rinds until Utopia comes calling. No, they rolled up their sleeves, and by golly they set about making that future happen. I don’t know if I’ve ever read a story more willfully blind to Human Nature.

If you’re looking for ways in which science fiction can inspire, here’s something the hope police may have forgotten to mention: if downbeat stories inspire despair and paralysis, it’s at least as likely that upbeat stories inspire complacency. Yeah, I know the planet’s warming and the icecaps are melting and we’re wiping out sixty species a day, but I’m sure we’ll muddle through somehow. We’re a resourceful species when the chips are down. Someone will come up with something. I read it in a book by Kim Stanley Robinson.

*

In fact, Kim Stanley Robinson is a good example. He’s no misty-eyed Utopian by any stretch, but he’s certainly more hopeful in his imaginings than the Atwoods and Brunners of the world. He recently pointed to the Paris Agreement as a “hopeful sign“:

It was a historical moment that will go down in any competent world history … That moment when the United Nation member states said, “We have to put a price on carbon. We have to go beyond capitalism and regulate our entire economy and our technological base in order to keep the planet alive.”

Surely I can’t be the only one who sees the oxymoron in “put a price on carbon … go beyond capitalism”. The moment you affix a monetary value to carbon you’re subsuming it into capitalism. You’re turning it into just another commodity to be bought and sold.

Granted, this is better than pretending it doesn’t exist (I believe “externalities” is the term economists use when they want to ignore something completely). And Robinson is no fan of conventional economics: he dismissed the field as “pseudoscience” at Readercon a few years back, which was heartening even if it is so obvious you shouldn’t have to keep coming out and saying it. But the moment you put a price on carbon, it’s only a matter of time before some asshole shows up with a checkbook and says “OK— here’s your price, paid in full. Now fuck off while I continue to destroy the world in time for the next quarterly report.” Putting a price on carbon is the exact opposite of moving beyond capitalism; it’s extending capitalism into new and more dangerous realms.

Citing such developments as positive makes me a bit queasy.

I got the same kind of feeling when everyone dog-piled all over David Wallace-Wells “The Uninhabitable Earth” in New York Magazine this past summer. Wallace-Wells’ bottom line was that even the bad news you’ve heard about climate change is a soft-sell, that things are even worse than the experts are admitting, that in all likelihood large parts of the planet will be uninhabitable for humans by the end of this century.

It took about three hours for the yay-sayers to start weighing in, tearing down that gloomy-Gus perspective. They tried to pick holes in the science, although ultimately they had to admit that there weren’t many. The main complaint was that Wallace-Wells always assumes the worst-case scenario— and really, things probably won’t get that bad. Even Michel Mann, one of Climate Change’s biggest rock stars, weighed in: “There is no need to overstate the evidence, particularly when it feeds a paralyzing narrative of doom and hopelessness.” This turned out to be the most common criticism: not that the article was necessarily wrong overall, but that it was just too depressing, too defeatist. Have to give people hope, you know. Have to stop being all doom-and-gloom and start inspiring instead.

I have a few problems with this. First: Sorry, but when you’re driving for the edge of a cliff with your foot literally on the gas, I don’t think “inspiration” is what we should be going for. We should be going for sheer pants-pissing terror at the prospect of what happens when we go over that cliff. I humbly suggest that that might prove a better motivator.

Further, describing the worst-case scenario isn’t unreasonable when the observed data keep converging on something even worse. Science, by nature, is conservative; a result isn’t even considered statistically significant below a probability of at least 95%, often 99%. Global systems are full of complexity and noise, things that degrade statistical significance even in the presence of real effects— so scientific publications, almost by definition, tend to understate risk.

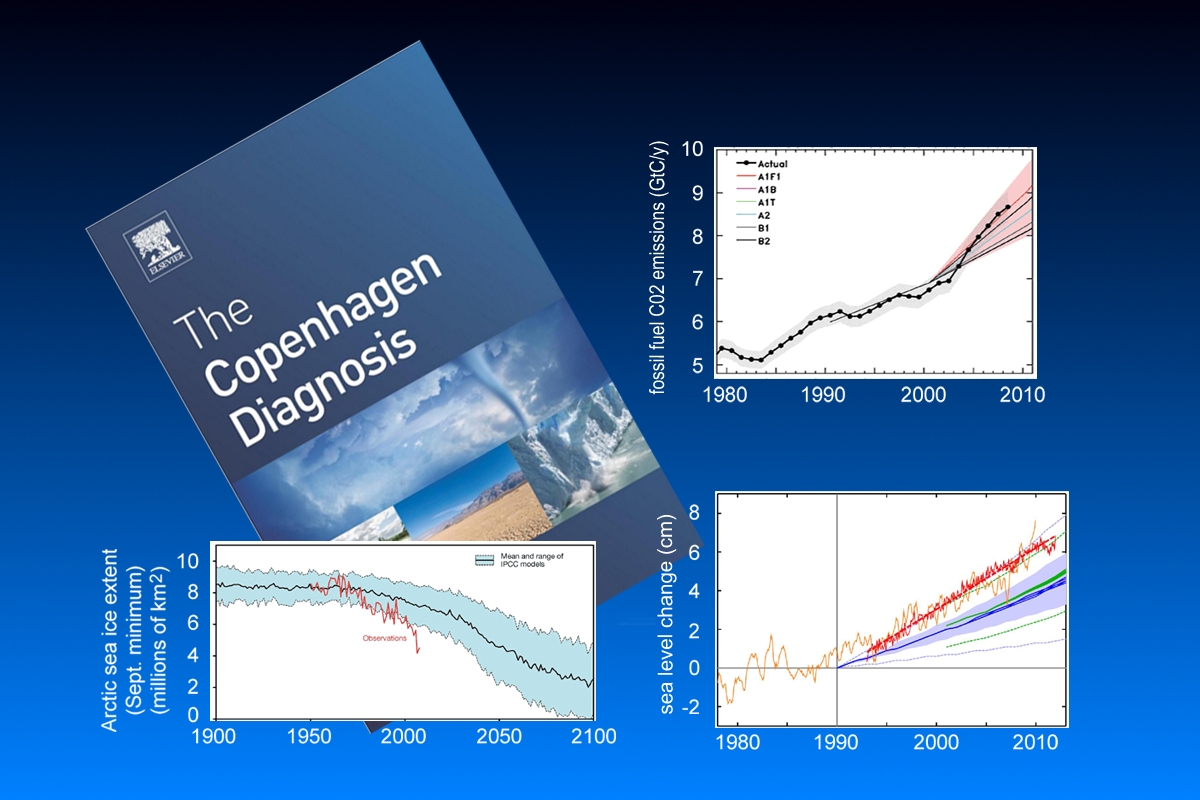

Which might explain why, once we were finally able to collect field data to weigh against decades of computer projections, the best news was that observed CO2 emissions were only tracking the predicted worst-case scenario. Ice-cap melting and sea-level rise were worse than the predicted worst-case— and from what I can tell this is pretty typical. (I’ve been checking in on the relevant papers in Science and Nature since before the turn of the century, and I can remember maybe two papers in all that time that said Hey, this variable actually isn’t as bad as we thought!)

So saying that Wallace-Wells takes the worst-case scenario isn’t a criticism. It’s an endorsement. If anything, the man understates our predicament. Which made it a bit troubling to see even Ramez Naam— defender of dystopian fiction— weighing in against the New York piece. Calling it “bleak” and “misleading”, he accused Wallace-Wells of “underestimat[ing] Human ingenuity” and “exaggerat[ing] impacts”. He spoke of trend lines for anticipated temperature rise bending down, not up— and of course, he lamented the hopeless tone of the article which would, he felt, make it psychologically harder to take action.

I’m not sure where Ramez got his trend data— it doesn’t seem entirely consistent with what those Copenhagen folks had to say a few years back— but even if he’s right, it’s a little like saying Yes, we may be a hundred meters away from running into that iceberg, but over the past couple of hours we’ve actually managed to change course by three whole degrees! Progress! At this rate we’ll be able to miss the iceberg entirely in just another three or four kilometers!

*

I don’t mean to pick on Ramez, any more than on Favro— having recently hung out with him, I can attest that he is one smart and awesome dude. But. Try this scenario on for size:

You’re in your living room, watching Netflix. You look out the window and see a great honking boulder plunging down the hill, mere seconds from smashing your home to kindling. Do you:

- Crumple into a ball of weeping despair and wait for the end;

- Keep watching Stranger Things because that boulder is just a Chinese hoax;

- Wait for someone to inspire you to action with tales of a hopeful future; or

- Run like hell, even though it means abandoning your giant flatscreen TV?

This underscores, I believe, a potential flaw in the worldview of the hope police. It may be that despair and hopelessness reduce us into inaction— but it may also be true that we simply aren’t scared enough. You can thank our old friend Hyperbolic Discounting for that: the future is never all that real to us, not down in the gut where we set our priorities. Catastrophe in ten years is less real than discomfort today. So we put off the necessary steps. We slide towards apocalypse because we can’t be bothered to get off the couch. The problem is not that we are paralyzed with despair; the problem, more likely, is that we haven’t really internalized what’s in store for us. The problem is that our species is already delusionally optimistic by nature.

Not all of us, mind you. Some folks perceive their contextual status with relative accuracy: they’re better than the rest of us at figuring out how much control they really have over local events, for example. They’re better at assessing their own performance at assigned tasks. Most of us tend to take credit for the good things that happen to us, while blaming something else for the bad. But some folks, faced with the same scenarios, apportion blame and credit without that self-serving bias.

We call these people “clinically depressed”. We regard them as a bunch of unmotivated Debbie Downers who always look on the dark side— even though their worldview is empirically more accurate than the self-serving ego-boosts the rest of us experience.

Judged on that basis, chances are that even most dystopias are too optimistic. Telling us that we need to be more optimistic is like telling an already-drunk driver to have another mickey for the road. More hope and sunshine may be the last thing we need; just maybe, what we need is to catch sight of that boulder crashing down the hill, and to believe it. Maybe that might be enough to get us moving.

*

The distribution isn’t a clean bimodal. Sure, there’s a clump of us here at the Grim Dystopia end of the scale, and another clump way over there at the Power of Positive Thinking. But there’s this other place between those poles, a place that mixes light and dark. A place whose citizens say You may not like it but it’s gonna happen anyway, so why not just settle back and enjoy the ride?

I see it when Terri Favro waves away the implications of smart homes that drain our savings into the coffers of retailers we never met in exchange for products we never asked for, with a shrug and a cheery “How many of us can resist the lure of the new?” I see it when I read articles in Wired that rail against our ongoing loss of privacy, only to finally admit “We are not going to retreat from the cloud… We live there now.” Or that more recent piece— just a couple of months back— which begins with ominous descriptions of China’s truly pernicious Social Scoring program, segues into it’s-not-all-bad Territory (Hey, at least it’s more transparent than our own No-Fly Lists), and finishes off with the not-so-subtle implication that it’ll probably happen here too before long, so we might as well get used to it.

It’s almost as though some Invisible Hand were drawing us in by expressing our worst fears, validating them to engender trust— and then gently herding us toward passive acceptance of the inevitable. “We’ll be giving up our privacy, but gaining the surprise and delight that comes with something new always waiting for us at the door!” Can’t ask for more than that.

Not unless you want to end up on the wrong kind of list, anyway.

*

These aren’t huge leaps. Inspiration Not Despair segues into Look on the Bright Side which circles ever closer to Accept and Acquiesce. There are, after all, a lot of interests who don’t want us to believe in that boulder crashing down the hill— and if said boulder becomes ever-harder to deny, then at least they can try to convince us that it really isn’t so bad, that we’ll learn to like the boulder even if ends up squashing a few things we used to value. There’s always a bright side. The planet may be warming, but it’s not warming as fast! Just another few kilometers and we’ll be past that iceberg! See, we’ve even put a price on carbon!

Of course, if you really need to blame someone, look no further than those naysayers over in the corner; they’re the ones who didn’t Dream Big. They’re the ones who failed to Inspire the rest of us. Don’t blame us when the boulder squashes you flat; blame them, for “making us all fear technology”. Blame them, for failing to “show an array of trajectories out of the gloomy toilet bowl we’re spiraling”.

In fact, why wait until the boulder actually hits?

Blame them now, and avoid the rush.

[1] To borrow a brilliant term from David Roberts, whose piece in Vox ably defends Wallace-Wells’ prognosis.

[2] If you want a cinematic example of this mindset, check out Roberto Benigni’s insipid 1997 film “Life is Beautiful“, whose take-home message is that the best way to ensure your child’s survival in a Nazi death camp is to trick him into thinking that it’s all just an elaborate game and nothing can possibly hurt him.

The sacrifice of personal privacy to the benevolent digital gods of Amazon, Facebook, and Google is surprisingly tolerated. About a year ago I went to skeptics club meeting at the University of Victoria (Bio-Psych combined major here), on the topic of cryptography. A young guy, maybe 17, math and computer wiz, was hosting. What was so bizarre to me was how he’d seemingly already drunk the corporate kool-aid (Anything to get an edge as a prospective hire?) by expressing how he didn’t really mind the big tech boys collecting all his meta-data, since all it meant was the ads he was receiving were more interesting. The possibility of misuse of that data? Of manipulation? Impossible. After all, googles informal slogan “Don’t be evil” should assuage even the most skeptical.

But it’s only going to get worse. As machine learning improves, the ability of these corporations to manipulate will only grow. Tell the AI “sell this product”, and watch and wait as it makes a few stumbling errors, baby’s first attempts at broad manipulation. Oh, isn’t it just darling how it’s simply going for mass visibility? How 20th century. Then it starts taking advangate of massive pools of user meta-data. Then it determines points of maximum vulnerability for targeted advertising (Tired? Stressed? Reduced cognitive control? We have the answer for YOU!). And now, with corporate interests controlling the basic flow of information on the internet, the potential for programmability of humans is ripe. Do you remember the Facebook mood experiments? Amateurs. What’s the point if you can’t follow up with a sale? And money doesn’t even have to exchange hands, when all I really want you to buy is an idea.

“You want to convince me that SF can change the world?”

I mean, the arguments both for and against fictional dystopias and SF influencing society at large are nonsense. Very few people read anything, even fewer read anything that would make them think, and only a tiny fraction of this negligible minority gets the right message from what they read.

On a more optimistic note, the effects of climate change will soon become disastrous enough to make us stop worrying about privacy and government surveillance and the machines taking over. The Grim Dystopia is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.

I’d say it goes beyond that.

Humans consistently, systematically exaggerate both the extent and the coherency of media influence.

People blaming sci-fi for not inspiring people enough (or inspiring wrong kind of people to wrong kind of ideas) are falling victim to same weird cognitive glitch that makes people concerned that violent movies/games cause violence, or at least “cultivate mean world hypothesis” (this is free daily reminder that cultivation theory fans are yet to come up with a way to distinguish between “cultivates mean world hypothesis” and “attracts people who are prone to have MWH-type ideation” 😉 ), or say sex negative radfems and their ever-irrelevant counter-empirical claims of harm from porn/erotica/whatever.

It’s really quite peculiar how people choose to blame media phenomena for stuff come hell and high water.

Having said that, it would be nice if sci-fi painted a more positive picture of massive geo-engineering projects targeting carbon sequestration and whatnot (instead of usual catastrophism, though I do realize that “giant project to “design” climate” lends itself to disaster plots a little too well).

It would probably have no effect on actual deployment of said projects 🙂 but it would be nice nonetheless

I clicked on the link to “The Uninhabitable Earth”, then added it to Pocket to read later. Pocket threw up some suggestions for other, related articles. The first in the list was from the Daily Telegraph (British conservative broadsheet), with the title “No one ever says it, but in many ways global warming will be a good thing” (Bjorn Lomborg, of course).

Maybe this is the next stage for the people currently trying to deny the problem. We’re already being conditioned by quite a lot of bad sci-fi coming out of Fox News and Murdoch’s other ventures (among others): “In a world where capitalism had made everything just wonderful, a band of evil scientists invented a hoax that would trick us into hamstringing the economy …”. They’ve now moved through denial (“It isn’t real”) to minimization (“It won’t be that bad”). Once the reality and seriousness of the problem can’t be denied any longer, maybe the political Pollyannas will switch wholesale to telling us that climate change actually represents not a problem but a Wonderful Opportunity.

Well, that blurb back on one of your books about how reading your stuff saps the will the live? True enough, this is full-on Dr. Watts gloom and doom. Sadly and terrifyingly, it is all true enough.

I keep telling my mother that there is no way she will get grandkids, not with the ecocalypse looming so close. And still she insists that it is not all that bad, they thought the end was near in the 80s too, and so on. And my mother is a smart and well-read women..

That being said, will continue watching Netflix and snarfing Pork Rinds, because it seems to me that it is way too late for the Boulder not to crush us anyway, and id rather die with pork in my mouth than running.

“The fruit of that labor was Hieroglyph: Stories and Visions for a Better Future; a number of my friends can be found within its pages, although for some reason I was not approached for a contribution.”

Probably for the same reason Mengele was not approached to contribute to the journal of bioethics, I might think. /s

Thanks for the jerk out of complacency!

A modification to your boulder analogy is that the entire family is chained together, and if one of us chooses not to move (perhaps snarfing porkchops…) it’s a damn sight harder for the rest of us.

I would argue that a lot of dystonia just relabel the anxiety into some impossible scapegoat (superbugs & zombies, AI & robot uprising, etc.). Which is worth arguing against. Points us away from the reality of what we’re facing.

Your points on optimism vs pessimism and the dangers of complacency in SF are well taken, but I think the problem is that no matter how well intentioned, most people simply start to tune out after a certain point of too much pessimism, nonstop dystopias, and “you are bad and everything you know is wrong” sermonizing. It doesn’t matter that you may be right if nobody reads SF any longer because it becomes just such a fucking bummer.

Understandably you’re protective of your own niche. It would be nice, however, to be able to accept the reality of this and find a middle ground between simple escapism or Zuckerbergian “pay no attention to the the man behind the curtain” pro-tech cheerleading, and cultivated disdain for any SF that doesn’t make you want to kill yourself.

Dystopia is right outside the window. Getting spit-roasted by big nonstop thorny dongs of pessimism in both ends by reality and recreational intake is cognitively taxing at best, and truly physically oppressive for someone like me who’s biologically depressive. Don’t take this the wrong way–Peter Watts is an important part of my recreational intake–but if all SF was Peter Watts, I wouldn’t read it anymore. How many great ideas and important, expansive speculation would I be missing out on then?

The reality is that wonder, discovery, and big expansive ideas and shameless optimism *were* a big part of the science fiction from the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s I read growing up, and to the best of my ability to filter the inevitable nostalgia, I don’t get the same feeling from most contemporary SF. I personally enjoy SF that is content to leave the mundane posturing over societal issues to genres better suited for it, and instead explores the fabric of reality itself. A lot of contemporary pessimistic SF may be more “credible” from certain points of view, but I’m not sure I’d have ever become a fan if that was all there was when I was growing up.

My personal notion of ideal “optimistic” SF would be stuff that calls out and acknowledges the downsides of modern tech, while still making a case for how it might be dealt with and moved beyond. Is it as *likely* as a more pessimistic appraisal of where humans are headed? Probably not. But it keeps me reading, and it keeps me thinking about the things the writer wants me to think about.

“People are shitty animals, everything is horrible, and you’re all going to die” is a true story, but it’s also an old one that everybody learned at a young age. What else have you got?

[…] Denying Dystopia: The Hope Police in Fact and Fiction 9 by jseliger | 5 comments on Hacker News. […]

> Blame them now, and avoid the rush.

Some of us have been blaming you for a decade or so now. I’m not inclined to stop just because it’s going mainstream – I’ll wait until the inevitable over-correction, of course.

> You want to convince me that SF can change the world?

You presuppose a belief in the possibility of convincing you (collective) of anything at all. I’m beginning to wonder if that scepticism (theirs not yours) isn’t at the bottom of some (most?) of our ongoing socio-political problems.

Brilliant opinion piece, Peter. One that drives knives into the heart of reality-deniers everywhere. Thank for for expressing it so sharply and eloquently.

Honestly, I think someone in a thousand years might pull it off a fossilized hard drive and take a deep breath (if they’re still carbon-based) at its prescient gravitas.

Thank you for having a contrary opinion!

“Inspiration Not Despair segues into Look on the Bright Side which circles ever closer to Accept and Acquiesce.”

Can I quote this line?

Reminds me of Schopenhauer: “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.”

We’re still in the ridicule phase.

If Amazon were choosing my purchases, it would be just a series of alternative versions of the last thing I bought with some women’s clothing and jewellery thrown in for some reason.

I wonder if any of those criticising the dystopian peddlers has taken a moment to look at the very simple way we go about motivating populations in time of war (justified or manufactured) – why, funnily enough we tell them the most fearful stories about what will happen if we don’t all pull together and sacrifice for victory, right now. Those monsters will rape our women, enslave our children and eat our babies. They have weapons that can vapourise cities in milliseconds, and they will use them! It’s beyond obvious that the only way to motivate and achieve action at a population level is through fear and creating an urgent sense that we must act now, or we perish.

I can only think those wanting to play up the bright side of everything are a bit deluded. Or possibly it’s what Russian troll-farmers do when they need a break from all the negativity – same societal level disruption, but they get to say ‘nice’ things for once 😉

Not really the same thing. War propaganda dehumanizes others and casts the target in a heroic light–a narrative human beings are all too eager, even wired, to gobble up. Pessimistic SF, at least in the minds of the authors, is holding up a mirror, casting the people reading it as the monster (by virtue of being a member of the human race)–a much more difficult sell and one people are inclined to reject, especially if it seems like that’s the only thing on offer.

Pessimistic SF is a vital part of a healthy and varied SF landscape. That landscape becomes less healthy if it starts to skew too far in one direction or another. To far one way, and all you have is toothless, complacent escapism. Too far the other, and the body becomes equally impotent as people start to reject it wholesale and your impact is limited to preaching to the already converted who stick with you because it reinforces their own opinion.

In order to peddle one’s wares, you need to get your foot in the door. If they see you coming with your sackcloth and “the end is nigh” sign, they’re going to lock the door and release the hounds. It doesn’t matter if the end might actually *be* nigh, or if you might actually have some worthwhile insight–you’re going to get rejected because of the resemblance to all the other people currently riding into town on their impossibly high, vaguely skeletal horses, peddling their trite baubles of casual outrage and gloom.

[…] Peter Watts doing what he does best; worth reading in full. […]

Have you come across the concept of Depressive Realism? I think that when you say clinical depression, you might be referring more to DR. The concept basically stems from the idea that those with mild depression are prone to make more logical/rational judgments. My intuition is that the inverse is also true and that those who are more rational about the nature of the universe and don’t shy away from it are somewhat depressive as a result. The psychotherapist Colin Feltham has written much on the subject and his book, Keeping Ourselves in the Dark (which has been on my to read list for a long time) covers a lot of the issues of self deception and optimism bias that you’ve pointed out here. There is a good interview transcript where he discussed some of this here: http://www.knunst.com/planetzapffe/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Interview-Colin-Feltham-2014.pdf

Hell, if Favro’s right it won’t bother trying to sell us anything at all; it’ll cut us out of the loop entirely, negotiate with our Smart Home, and send us those shoes from Paris without even telling us. And, after maybe a few rebellious post-purchase returns to prove we’re still in control, we’ll settle down and stop fighting and let Alexa be a good little consumer in our name.

I think Greg Benford is into that in a big way— he used to be, at least. And I myself have incorporated geoengineering into my worldbuilding in stories dating back to Maelstrom. But you’re right when it comes to asking for trouble: cool down the planet via stratospheric sulfate injection (instead of by, say, reducing carbon consumption) and you’ve cranked the heat up to “Venus” the moment someone interrupts your injection schedule.

If you want upbeat, I am heartened to see renewables taking off; that’s happening way faster than I expected. I think other factors mitigate the cheering, but it’s still a hopeful sign.

Oh, they’ve been doing that for well over a decade. “More carbon dioxide? Faster crop growth! Warming planet? Agricultural belt widens to higher latitudes!”

Right. Too bad wheat doesn’t grow that well in peat moss…

You know, that’s actually one of the better reasons I’ve seen for sitting out the apocalypse…

And why wasn’t he? I’ll tell you: because Big Ethics was too chickenshit to “Teach the Controversy”!

Me personally? Well, I’ve got ruminations on the functional utility of consciousness, and the implications of Darwinian selection in the context of digital ecosystems, and over there I’ve got intelligent clouds and a living membranous Dyson Sphere. And space vampires, if you’re into that.

I’ve said elsewhere that I don’t actually regard myself as a dystopian writer in the sense of Brunner and Orwell; I don’t write stories about dystopia so much as I write stories about other things set against a dystopian backdrop, and the only reason that backdrop is dystopian is because it would simply be implausible to posit a near future that’s all rainbows and puffy kittens. Would you describe “The Wire” as a show about automotive engineering? There are cars in every single episode, after all…

Also don’t forget I’m skeptical of this whole “SF Can Change The World” thing anyway. I may not be selling what you think I’m selling.

Oh, don’t I know it. Once I was blamed for misogyny over a story that didn’t even have human— or even biological— characters. Whole thing was told through the eyes of an AI.

Only if you restore the damn italics.

I hear you. Amazon keeps trying to sell me my own books.

Damn. That’s an excellent point. I wish I’d thought of it.

Speaking of Russian troll-farmers, does anyone here know why I suddenly belong to a facebook group called “Russia and Allies versus globaliZation”?

Fuck. That too is a good point. Maybe I can mitigate it by wondering if the reader isn’t implicitly cast into the role of Heroic Nonconformist by simple virtue of the fact they’ve chosen to experience such socially-aware literature in the first place, as opposed to the latest pap from Harlequin. It’s kind of meta, but it might save the argument.

I have; my understanding is that it’s been explicitly put forth as a replacement for “clinical depression” (in the same way “bipolar” replaced “manic-depressive”).

It’s a good term. I like it.

Oh yeah. Dr Watts is all about Depressive Realism.

The problem with holding up DR as some sort of superpower of the clinically depressed, is that there is plenty of other evidence suggesting people in depressed states are operating in a mentally diminished capacity. Bi polar creatives do their best work in their upswings, because their brains aren’t functioning at capacity during their depressive episodes. Handel wrote the Messiah in one of his manic phases.

As someone prone to depressive episodes, and who’s going through a particularly rough one right now, I can testify to this. Being depressed is like being hungover all the time, without the previous night of fun. I’m generally a very articulate person, but I have been struggling to get my thoughts out here in a coherent fashion through the fuzz.. It feels like I’ve easily shed about 30 IQ points.

So while people determined to make a pessimistic or nihilistic case about the state of the world like to cite this little tidbit, with the implication that people who refuse to see it that way are dumb or irrational, the choice isn’t that clear. The actual choice is more complicated–less deluded but “dumber” and lacking the ability to solve problems, or deluded but “smarter”, with the potential capacity to actually solve the problems that make life so shitty.

I know which I’d prefer. God, whatever happens to my brain during an up episode, we need to bottle that shit. Capable of going days without sleep, artistic output tripled, notebooks filled with ideas, and the downside is that I’m no longer capable of seeing myself as shitty as I am? Yes please.

***

For whatever it’s worth to you, the fact that I might come to the “correct” conclusions when I’m depressed seems entirely incidental. While you might be much more aggressive in filtering out the more optimistic but irrational interpretations of data that makes normal functioning possible, you’re also highly dismissive of any sound evidence that doesn’t conform to the most negative interpretation as well as the possibility of *new data*.

You could take me out of my current life and drop me in some future utopia where all my problems were solvable, mental functioning could be re-wired at will, all the empirical evidence suggests a high possibility of a rewarding life, and I would *still* be depressed. The fact that the world is empirically shitty, and I am also empirically shitty, just makes it easier for me to make a case I’m determined to make in any event.

Massive geo-engineering is absolutely predisposed to lead to an unforeseen disaster along the way. Seeing as we germans seem to be unable to even construct a train-station, airport or concert house without years of delays and billions of euros squandered, i shudder to think of those same government agencies planning a planet-rescue operation.

And companies probably would be even worse. There is a gem of a Sci-Fi game called “The Surge” that shows all too well what happens if some Googlecorp with no foresight, no oversight and no real investment except Shareholder value tries its hand at being the saviour of the earth. It doesnt go well, to make an understatement.

You should totally try that game Dr. Watts, the sheer hopelessness would appeal to you i think 🙂

No, not you personally. Sorry, that was a generic “you” pitched out into the void to some theoretical “you”. I do that all the time. It’s a regrettable defect, and frequently gets me into trouble when opinionating.

I love your space vampires and assorted speculative gee-whizzery. It’s why I show up for a Wattswork. Often I love them in spite of your aggressively pessimistic stances.

But it costs me something to read your books. Which is good…nothing worthwhile is free. Sometimes the price is awfully high, though, and I do fear that it is entirely possible for too many joyless contemporary SF writers to tax their fragile and largely inherited audience out of existence. Optimism and wonder may be dirty words if you want SF “cred” now, but they played a big part in creating that audience in the first place.

I didn’t know that had been proposed, and wonder if that proposal retains the meaning Feltham talks about as well as the traditional meaning of severe/clinical depression. I’ve been thinking of them as distinct.

Oh I certainly don’t think it’s a superpower and as I understand it, the improved judgement was associated with milder depression, with more severe/clinical forms being associated with worse than normal judgement.

Your other insights are very interesting, thanks. I am perhaps one of those people determined to make a pessimistic or nihilistic case. From my perspective that arises from a position of rational judgement and then any depressive tendencies follow from that (I do not consider myself to have depression). That is why I propose a reverse causation may be the case in certain instances of DR. But then, that is from my perspective, in reality I suspect there isn’t such a simple cause and effect and the two feed into each other.

I think part of the reason that climate models are consistently too positive over the last 30 years is that climate scientists are unused to dealing with non-linear effects or even imagining the worlds climate as a dynamical system.

A pattern I noticed almost 20 years ago when following climate change is: “We predict this change will happen no sooner than and will proceed at this rate to this extent” And then what happens is that the change occurs sooner, proceeds at a much higher rate and to a far greater extent than predicted.

The follow up was worse, it’s when I realised that the polical/economic/cultural institutions that govern us are incapable of reforming themselves to the extent necessary to stop catastrophe.

So yeah, we’re fucked, it’s going to happen sooner than expected, I’m betting social collapse across the OECD countries by around 2025-30.

Oh, and if you think social collapse is too grim, go and read Gwynne Dyer’s Climate Wars.

I haven’t noticed any boulders rolling toward my house. Instead (perhaps), I continually notice greedy behavioral patterns in folks whose rely on government funds, i.e. money looted from taxpayers.

From the perspective of a skeptical Regular Joe, which is more likely: that i) an invisible force will end life as he knows it in his children’s lifetime, or ii) an army of state-funded scientists who advocate in favor of more taxes and more government control, as their paymasters expect, will bend the truth or outright lie in order to feed a narrative that keeps their gravy train rolling?

Item “ii” seems far more likely to me. Dark politics infects everything when “free money” is involved, not even empiricists are immune.

Plus, there’s a medieval, religio-apocalyptic overtone to the climate change narrative. Most commentators here who favor carbon controls are not climate scientists, have not crunched the data and admit to merely trusting climate scientists at their word.

We know war is the health of the state. People are willing to change their lifestyle during periods of crisis, assuming they believe in the cause. You lament the massive, fascist surveillance state which was justified by bullshit corporate-state crisis propaganda, disillusioning hundreds of thousands of skeptics, then you question why more of the same doom porn isn’t directed toward the real threat, which happens to be invisible and must be taken on faith by 99% of people, so that the royal “we” will be saved. No thanks, Peter. If skepticism of the matter makes me anti-science, then so be it.

Here’s a not-so-invisible crisis: western governments have unfunded liabilities which literally enslave future generations. Unborn generations! This is perhaps the only crisis that overspending governments (oxymoron) actively avoid discussing in PR forums, going so far as to manufacture crises as a distraction–one reason I’m skeptical of the climate change narrative. Only time will tell.

While it may be that item “i” above is true, for now I say come what may and choose to focus my advocacy elsewhere, namely that the clear and present danger to humanity are tyrannical monopolies of violence. At this point in history, to advocate in favor of climate controls is to feed the enslaving leviathan, rather than to rip it apart, tentacle by tentacle.

That’s kind of like saying that people with cancer who are not oncologists have not diagnosed themselves with the disease, and admit to merely trusting doctors at their word.

Which sets a rather high standard for believing… anything.

Also, promoting climate controls seems to go very much against the interests of ‘tyrannical corporate statists’, many of whom have considerable investments tied up in fossil fuels.

All money is government money, so I’m not sure what to make of this statement.

My one consolation is that all the “regular Joes” who dont trust the big gubbinment and all the evil evil scientists, will go down with the rest of us when our biosphere collapses, regardless of how many guns they hoard in their little libertarian utopias.

Because the nature and the universe dont give a flying shit about what people believe or not believe, and who the “real” enemy is, be it the Judean Peoples Front or the Peoples Front of Judea.

BTW it’s a little odd that you deem climate change (and its rather visible effects) “invisible”, while the debt crisis, which is based on nothing tangible or real, is sufficiently “visible” to result in such portentous predictions.

[…] Peter Watts makes an argument in favour of the dystopia in contemporary science fiction. https://www.rifters.com/crawl/?p=7809 […]

Not really. It’s analogous to a group of oncologists informing a group of individuals that they have cancer, advising that they should pay for treatment, even though the individuals don’t feel like shit.

Certainly I’m not the only objective person who has witnessed little change to the climate in my part of the world over the last 30 years.

What is more, some individuals take the oncologists at their word and push to make a law whereby all individuals must pay for a checkup with an oncologist.

Corporations can afford regulatory compliance, whereas most small businesses, especially startups, cannot. In the long run, as with all regulatory apparatuses, corporations would come to appreciate carbon controls, because it would drive potential competitors into less regulated economic sectors.

Lol. Money is store of value, nothing more. Value is created by actors in the marketplace, regardless of what store of value is used for transactions. Government does not create value, at least it can’t create value without significant opportunity cost.

Ayn Rand pretty well summed up money in D’Anconia’s Money Speech from Atlas Shrugged. Google it. Or check out Rothbard’s What Has Government Done to Our Money.

It’s not a prediction, Fatman. As long as the gubbiment fancies itself solvent, meaning as long as it can jail you for failing to pay taxes, future generations are on the hook for terrible decisions of the past. It is taxation without representation, pure and simple. It’s slavery.

As I said, the climate in my part of the world hasn’t changed in thirty years. I have two young kids and there is no question, at this time, that unfunded liabilities are more likely to significantly affect their lives significantly than climate change.

Things change, of course. I’m just shooting the alligators closest to me.

Oh, look, people. Today’s first science denier. Gather round.

Here, let me fix that for you:

From the perspective of a skeptical Regular Joe, which is more likely: that i)

an invisible forcethe laws of physics willend life as he knows it in his children’s lifetimeresult in periods of massive environmental instability ranging from melting ice sheets to droughts and firestorms (except, apparently, around Witchita), or ii)an army of state-funded scientists98% of scientists with relevant expertise, whether funded by the state or required to bring in their own funding from external sources because the state has stopped funding pure research whoadvocate in favor of more taxes and more government controldraw common and broadly-consistent conclusions based on a wide range of data from field ranging from paleoclimatology to biogeographyas their paymasters expecteven in the face of ongoing government muzzling and censorship,will bend the truth or outright lie in order to feed a narrative that keeps their gravy train rollingeven though they could make vastly more money by switching sides and getting on the Exxon/Koch payroll that owns so many of their political masters?Not to fuck too much with your narrative, but I’ve read some of those papers. I used to read a lot more of them, but I dialed back about a decade ago when each new finding seemed to merely reinforce the previous ones. And while I may not be a climate scientist, I do have a PhD and a couple of post-docs in biology; I’ve seen a fair bit of raw data on the timing of migrations, the epidemiological spread of various pathogens, expansion of parasite ranges due to climate-mediated host-switching— a whole shitload of stuff, actually. And it’s all consistent with what the climate scientists have been reporting from over in their domain, based on mountains of data that range from glacial ice cores all the way up to orbit. If it is all a hoax, it is an epic motherfucking masterpiece of multivariate verisimilitude.

Uh, no. The whole point of science is that it doesn’t have to be taken on faith. It can be tested, it can be replicated. It can be disproved; it’s not a scientific hypothesis if it can’t be disproved. And I’m pretty sure that if the whole climate change thing could be disproved— if all the retreating glaciers and bleaching corals and rising seas and intensifying firestorms and moving biodistributional ranges could all be shown to hail from some alien wanker in a flying saucer, fucking with the world for shits and giggles— someone, somewhere, would have taken that data over to BP’s head office and cashed a thank-you cheque huge enough to make all those state-sponsored scientists sit up and take note of where the real gravy train pulls up.

Maybe you’re thinking “99%” of the scientists who can attest to the reality of climate change? You’d be out by a fraction, but that would still make that remark orders of magnitude more accurate than anything else you’ve said so far.

Skepticism doesn’t. Outright willful blindness does though, totally. You are utterly anti-science.

Certainly not. Judging by your comments here today, you are certainly not one of those objective people.

If only the same could be said by the inhabitants of Tuvalu, or Fort MacMurry, or Australia, or California, or Frobisher Bay, or— or hell, even here in Toronto. It’s the middle of December and I was swatting mosquitoes off the wall the other day. That’s never happened before in all the time I’ve lived here.

So, does my anecdote cancel yours? Course not: arguing by anecdote is like swapping old wives tales, unless you can put some hard numbers on it. And decades of hard numbers, rigorously derived by thousands of experts with virtual unanimity across a range of relevant disciplines, show that—

Oh, wait. You’ve already immunized yourself against any number I might cite, any paper I might send your way, even the links and figures a few screens up on this very page. None of that will sway you, because it all comes from — as you put it— an army of state-funded scientists who bend the truth or outright lie. You have no evidence of this claim— at least, you’ve presented none here— but that’s to be expected. Fundamentalists don’t need evidence; they’ve got certainty.

Look, I don’t expect to change your mind on this. Too many cognitive effects from Backfire to Kruger-Dunning are churning away in there, making damn sure you reject any worldview that doesn’t enhance social standing in your chosen tribe. (It’s a shame, really; we’re all subject to those glitches, but the thing about science is that it can drag you kicking and screaming towards the truth regardless. You should try it some time.) The most I can do here is hold you up as an example to others; point out the fallacies and the misrepresentations, the glaring defects in logic, the ad hominem slurs directed at armies of scientists you’ve never met (and whom I have, by the way. Dozens of them), just so you can dismiss their data and their analysis without having to look at it. You haven’t noticed the climate changing in Wichita. I guess that settles it.

Also you might want to stop using the word “oxymoron”. It doesn’t mean what you seem to think it means.

Here it is, rs and Ks. What I’ve been telling you all about.

It isn’t pretty, is it?

Peter Watts,

Nice work on the Shruggalo. I never fail to be amused when such people hold themselves up as paragons of scepticism, when what they’re displaying is the credulity of a True Believer.

Objective person.

Objectively a person.

Objectivist Person.

Not to pile on EMP here–I’ve got my own streak of scientific skepticism aimed in particular at psychology and tangential human studies in the wake of the Replication Crisis (on Infinite Earths!)–but that was an interesting turn of phrase. I’d go so far as to describe “objective person” as an oxymoron, but that may be a sore subject.

Touche, DA. Objective person is somewhat of a contradiction in terms.

I’m fleshing out a response for Peter currently. Then you can pile on.

I dont have to google D´Anconias Speech, because i read Atlas Shrugged. I am sure a messianic John Galt Archetype will show up any minute, and monologue a coming superstorm in submission, when he isnt breaking the law of physics by pure willpower, of course.

And then he will lead the select few into a new, golden era, while all the sinners and unbelievers burn and perish. Somehow that narrative seems all too familiar to me.

Just dont forget to scream the magical phrase “AM I BEING DETAINED?!” at the firestorm/drought/typhoon/tsunami in front of you, i am sure reality will budge before your righteousness.

Enjoyable as that was, would you say that such people as in the minority or the majority of any given first world population? In my experience with a fair share of them, they tend to herald themselves as a paragons of a skeptical minority, where much discussion is a mixture of a typical gish gallop and JAQ’ing off seasoned with healthy doses of libertarian paranoia and persecution complexes to boot, with dashes of a messiah complex depending on tribes social ladder rung.

Think I could trouble you to toss a few of those my way? I’ve yet to read up on the biogeographic angle on climate change.

Yes, but that’s not to say people aren’t capable of reasonable degrees of objectivity if they acknowledge this as a starting point. It shouldn’t, for instance, be used as the basis for an “everything is unknowable” argument, if that’s where you’re going.

Oh, I do wish you wouldn’t. I thought I could watch Rand-spouting climate science deniers get dunked on all day, but faced with the savagery of that last shattered backboard, it turns out my stomach is a bit weak. I think on this subject, on this turf, you are at a disadvantage, and should stick to surer ground for you like ragging on the government–always a winner in some flavor or another. I don’t actually want to see that dogpile.

Speaking as a Poor Wannabe Libral, Down here in Gloriass Trumptowpiea.

All I can say is, HUUWEEEEEEEE Bruthers and Sisters can I get an AMEN on this one!!

The son of the preacher man done speak the TRUTH!!

Hey Peter,

Firstly, it’s really cool that you have an active blog with an active comments section. I just wasted 2 hours going down the rabbit hole.

Secondly, why do you think carbon tax is a bad policy? Pseudo-scientist here, I wrote and deleted a wall of text on why it’s the best approach, but you’ve probably put some thought into it. Any arguments, or you just think it’s not enough?

Layman to potential layman, I could be talking out of my arse here so bear with me but going by what Peter says in his post about how you risk associating carbon footprints with a monetary value, which I assume, would lead to actors attempting to game the system and try to minmax the rules, as opposed to genuinely try to cut down on it altogether.

Also, it sort of seems like putting a price tag on incremental damage to the environment doesn’t exactly stop said damage or deter it since as Peter so eloquently put,

Personally, my opinion is that I wouldn’t consider it bad policy per say, but I feel like it contributes to the illusion of something meaningful being done about the whole affair, whereas what it really does is put a price tag on the damage, which doesn’t seem to be too much of a deterrent to big industry actors, as you said, not enough.

Hi Petar, let me try and answer that.

I think a carbon tax is bad for the same reason that a civilian-casualty-of-war tax is bad.

Just as a civilian-casualty tax would incentivize gaming the death statistics by doing things that almost-but-not-quite count as killing civilians (and you wouldn’t want to live near any of those regions while the gaming was going on), a carbon tax would incentivize gaming the emissions statistics by doing things that almost-but-not-quite count as emitting carbon (and you wouldn’t want to live near any of those regions while the gaming was going on).

Carbon over-emitters can buy offsets by e.g. planting carbon absorbing forests, but these forests are sometimes unwanted by the local populations. Similarly, if you killed more civilians than you were supposed to in a war, you might want to encourage the production of new ones, but occasionally, no local population might want those new civilians.

As a carbon emitter, if you reduce emissions one year, you can over-emit the next; this might strike observers as gratuitous. Similarly, as a civilian killer, you could keep deaths to a minimum early in the war then use up all your savings when you’re pretty sure you’re about to win the war; this might strike observers as gratuitous.

(I hope anyone better-informed here will correct my analogy if it is way off the mark)

@Aazad,

Yeah, I get that, of course that companies will try to game the system. It’s just their profit maximizing nature, you can’t expect different. This is why you constantly fix the loopholes, as new ones are found. Sometimes all you have to do is *ask* industry experts for advice.

RE: the asshole with the checkbook, that just means that the tax is not high enough. Just raise it over and over, until it becomes prohibitively expensive to use coal or whatever. Tax has the added benefit that it allows arbitrage over industries. E.g. let’s say it turns out that the cost of switching to clean cargo tankers is relatively lower than the cost of lowering meat consumption. What will naturally happen is that the shipment industry will make a cost-benefit analysis, switch to clean ships, and slightly increase prices. While the animal husbandry industry might find that it can’t innovate ways to reduce methane emissions, well, they just have to pay the tax, which increases prices, which decreases consumption of meat. You see what happens here? While a committee might reason that since cows release too much methane, we should cap the consumption of cow meat, a tax allows the most efficient reduction of GHG, which would allow us greater results for the same social cost. This is very good.

The tricky part is that you have somewhat less control over the results of such a tax, compared to just banning the offending products/industries. E.g. we have some data on how the consumption of cow meat has changed with the changing prices, so we can estimate elasticity, so we can estimate how a certain tax will affect consumption of cow meat, but the data is not free of noise and the data is not perfect. Moreover, pretty much every single industry and supply chain will be affected by such a tax, so doing all of these calculations becomes a herculean task, even if you relax your standards. There are ways around that, of course, you can estimate the cost increase for a basket of goods or a subset of all industries and extrapolate, but again, it decreases the accuracy of the estimate. Further, you cannot predict what kinds of innovations will happen to decrease the costs that come with GHG emissions.

So you can make an estimate on the effect of carbon tax, but such estimates become exponentially harder to do with the more accuracy you require. What do you do then? You just make a rough prediction, and see what happens. If the reduction is not enough, you increase the tax. If the reduction is too much, you might want to decrease the tax. If you are more concerned with the potential environmental impact, you want to overshoot the initial tax, better to be safe then sorry. If you are more concerned with the social cost, you might want to be more conservative with your initial estimate and the adjust it in the future.

There is also one added bonus that you’re all overlooking, namely, that establishing even a little carbon tax and putting it in place is good, since it would require very little legislative effort to increase it later on. You can even make the increase automatic, if certain benchmarks are not met. While if you ban all gas cars, as an example, and then find that the effect is not enough, you have to go through the same process to ban whatever else, which will take another several years of drafting legislation, opening it up for public comments, fixing the holes, and passing it.

That’s all. The blanket tax on carbon emissions is a very good policy, as long as you consider carbon emissions a good proxy for pollution. If it’s not a good proxy, find a better one.

I’m not sure I buy that argument. If the local populations don’t want the forests, they can negotiate a higher price for them.

Again, don’t see the issue here. As long as the carbon emitters are hitting their goals, why should the observer’s opinions matter? I’m seriously lost. The emitters presumably took some costs to cover the reduced emissions on the first year, because it was more efficient for them. If you don’t allow this sort of switching from year to year, they’re just going to hit the maximum every year; and you end up with no less emissions, but needlessly higher costs for the emitters.

I only read the first few paragraphs, but I’m going to drop this here… Maybe the thing to do is for every Science Fiction writer to examine both the utopian and dystopian aspects of any question, if only as an exercise. Self-Driving Cars? Why are they heaven? Why are they hell?

Did the coup already happen?

a reader, there’s a lot that doesn’t seem to make any sense, otherwise.

It’s kind of crazy how people have so much difficulty really perceiving the problems in our society. We can identify them sure, and we can even talk about them, but actually *feeling* them and being pushed into some sort of action in response? Practically impossible. People need to be dying in the streets for that to happen.

And honestly, I can feel myself being drawn away from it. Being angry over big-picture abstract things is hard, and once you realize the full depth and extent of the problem it can get extremely demoralizing. Shit is currently hitting the fan, has been for decades, and really it doesn’t seem to be letting up whatsoever. Might as well enjoy myself like everyone else, I guess.

Adam Chitwood on the upcoming fourth season of Black Mirror: “At least we’ll be entertained while the world’s going to hell”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=83&v=5ELQ6u_5YYM

I’ve read (unfortunately) Atlas Shrugged, and I did Google the speech to refresh my memory. Which means that I have wasted a second 30 minutes of my life on the same specious drivel, so I guess I deserve the LOL – you just Rick Rolled me.

Not sure where you live, but my dollar bills are issued by the US Dept of Treasury. I’ll keep looking for some that aren’t and will post results.

Ah, the “it’s still snowing here, therefore no global warming” argument. The pinnacle of climate-change-denier logic. You’re really pulling out all the stops here, sport.

What’s to say we can’t simply default on the unfunded liabilities? The D’Anconias of the world do it all the time, then come back and make even more money.

If considering a response on the possible negative impact of default, please make sure you list your credentials (a PhD in economics is a minimum) and provide evidence that you’ve crunched the numbers in support of your argument. I wouldn’t want to take anything on blind faith 🙂

That’s more or less it IMO. Offenders would simply pay the tax and associated fines and continue offending, since they are realizing superprofits from doing so. You could always up the tax to make it more expensive, but that would choke out smaller competitors and give even more power to the big players. Or you create a carbon credit trade system in which only the big guys benefit because they have more resources to play around with. EMP had a valid point here earlier on in the thread.

I would personally prefer efforts to be directed into improving the efficiency of use of renewables / non-polluting energy sources to kill off fossil fuels altogether. Tax revenues from carbon control could be used for that.

Hi Petar,

You’re right and I agree: carbon taxes will likely reduce global emissions. I only reached my opinions about carbon taxes recently so they’re not well-formed.

I’d like to convey an intuition: from a God’s eye view, any net reduction in carbon emissions is a plus. However, from a local’s point of view, letting people from far away pay to destroy my home (either by polluting it or forcibly planting carbon sinks) seems unfair, especially if I don’t get a say in how that destruction is carried out.

Oh, don;t worry. Once TSHTF, the libertarians will be elbowing the rest of us out of the way, trying to get on that there Big Gubbimint Handout train like it’s nobody’s business.

Ayn Rand did, after all.

My guess is that you joined an innocuous seeming group, like, just by way of random example, “Fluffy Kitties are the awesomest!” and at some point the owner/moderator of that group (who may or may not have been the original, lots of sites like these gather likes/followers with broad appeal and then sell them) changed the name to something you don’t agree with in the slightest. Seen it happen before.

It’s also possible that an actual cat is on your computer while you sleep and joining stuff on Facebook that matches its interests (you think they walk all over our keyboard for our attention? No, they’re trying to commandeer it).

“Looks like dangerous seas up ahead. I know! Let’s erase all the reefs from our nautical charts!”

As Bernard Moitessier wrote in The Long Way:

“She speaks to me then, and I understand that this is no miracle. And she tells me the story of the Beautiful Sailboat filled with men. Hundreds of millions of men.

When they set out, it was on a long voyage of exploration. The men wanted to find out where they came from, and where they were going. But they completely forgot why they were on the boat. And little by little they get fat, they become demanding passengers. They are not interested in the life of the boat and the sea any more; what interests them are their little comforts. They have accepted mediocrity, and each time they say ‘Well, that’s life,’ they are resigning themselves to ugliness.

The captain has become resigned too, because he is afraid of antagonizing his passengers by coming about to avoid the unknown reefs that he perceives from the depths of his instinct. Visibility worsens, the wind increases, but the Beautiful Sailboat stays on the same course. The captain hopes a miracle will calm the sea and let them come about without disturbing anyone.

[…]

Lots of the men are still sailors. They don’t wear gloves, the better to feel the life of the sails and the lines, they go barefoot and stay in touch with their boat, so big, so tall, so beautiful, whose masts reach all the way up to the sky. They don’t talk much; they watch the weather, reading the stars and the flights of gulls, and watching the signs the porpoises make. And they know their beautiful boat is headed for disaster. But they do not have access to the sheets or the wheel, they are a bunch of barefoot tramps kept at large. People tell them they smell bad, tell them to wash. Many have been hanged for trying to trim the after sails and ease the jibs to alter course at least a little. And the captain waits for the miracle to come between the bar and the saloon. He is right to believe in miracles … but he has forgotten that a miracle is only born if men create it themselves, out of their own being.”

To paraphrase Kim Stanley Robinson, capitalism killed utopian science fiction, the future, and perverts everything from robots to AI. What makes Watts’ SF tolerable is that he sees through the BS of how technologies are perverted by sociopolitical and human limitations. Robinson’s tolerable for the opposite reason, an optimist who sees technology and its effects tolerable only after emancipation from sociopolitical straightjackets.

Think you’re completely right, as usual.

I’ve just finished reading a lot of Phil. K Dick’s shorter work, and alongside a lot of his mainstream fiction, almost all of his short fiction seems to be set in a post-nuclear war setting. It almost stops being mentioned in some stories, just seems to fade in the expected background. This kind of thick, gooey all-encompassing pessimism is just the sort of happy thing we can smile back on from the present, as we should be able to smile back on the environmental pessimism of today in fifty years when, with luck, the situation is resolved.

Last time i looked we were all still one press of a button, intentional or otherwise, away from a nuclear holocaust. With the US Arsenal in the hands of an orange maniac, the Russians investing billions in refurbishing their doomsday stockpile, and rampant nuclear armament proliferation around the world, a (perhaps limited) nuclear exchange seems to be more likely every day. In fact, i would be surprised if, say, India and Pakistan DONT come to nuclear armed fisticuffs in my lifetime.

If anything, Phil K. Dicks work is way too utopian…we sure as hell wont get shiny offworld colonies in 2050 or so. The ruined landscape dotted with hydroponics that will serve us delicious Nutri-Slime seems all too real to me, though. All the more reason to cram as much tasty snacks into my mouth while i still can.

I’m gonna be an optimist and guess that deniers are in the minority, at least in the first world. It’s important to note, though, that the US does not really qualify as a first world country by a myriad of metrics ranging from infant mortality to homicide rate.

When I said “raw data”, that’s what I meant— I’m talking about other people’s pre-publication stuff from back around the turn of the century, when I was still in academia. But if you’re looking for the current picture, do a Google Scholar search on ‘alaska migration timing “climate change” OR “global warming”‘. You can throw in “seabird” or “fish” or “mammal” if you want to narrow the search taxonomically. You will find no end of peer-reviewed hits.

Sorry to be weighing is so late (had a couple of imminent deadlines); other commenters have pretty much covered my take on the issue. To sum up, though: I think a carbon tax is way better than ignoring carbon impacts altogether. I’m fully in favor of imposing some kind of financial cost if it can slow down the race towards the cliff, and/or fund the development of off-ramps. But when the FCC repeals Net Neutrality, Netflix doesn’t stop streaming shows; it simply caves to Verizon’s (once-again-legal) extortion, pays the higher up-front costs, and passes them on to its customers. Economic solutions can always be gamed by people with enough money; and since civilization is pretty much run by such people, they will always have enough money. (So long as economics runs the world, I don’t think your “raise [the tax] over and over, until it becomes prohibitively expensive to use” solution is going to work— or rather it won’t be allowed to work.)

More fundamentally, the tax approach mixes up the laws of economics (which are arbitrary, artefactual, and only tenuously connected to reality) with the laws of Physics (which will not budge and cannot be negotiated with). What we need, I think, is something that recognizes the inflexibility of physics. A binding policy that says “Nature’s not gonna change the ocean’s heat capacity, so we’re gonna have to stop trapping excess heat. Period. And if Exxon can’t buy it’s way out of the cap, tough.”

Of course, the world will respond with virtual unanimity that such extreme solutions are politically undoable. And they probably are. So we will continue to hurtle towards the precipice, and ultimately the problem will take care of itself. Because physics will, ultimately, prevail over politicians and economists alike.

Maybe we’re not on the same page with regard to how far the Titanic is from the iceberg. I’m of the “we don’t have time to dick around it’s already later than you think and all these experiments and trials will converge on a solution about three days after we break in half and sink into the abyss” school of thought. But I could be wrong.

I hope I’m wrong.

Oh, for sure. Or at least the field as a whole should certainly explore all alternatives, dy, u, and ambiguous hetero. But I’ve never argued otherwise: I’m not writing impassioned screeds telling people to “stop writing utopias”; I’m responding to screeds by those who say “No more dystopias.”

Bingo.

We’re just not wired to go into threat-response mode at the sight of graphs and scatter plots. We need to see a grizzly bearing down on us before we get off our asses. (What we really need is for someone to spike the water supply with some kind of contagious neurohack that does, somehow, connect the grizzly-response and graph-interpreting subroutines. Someone should write a story about that.)

Oh yes.

That is just about perfect. Except it attributes too much nobility to the starting state.

The elephant in the room is that optimistic sci fi has moved away from literature and into company PR departments.

I think it was Banksy who said that art suffers because everyone with talent can get a much better paying job in advertising. Why wouldn’t that be true for the literary art?

If you’re good at describing utopias, you know what people think they want. So you can write brochures and draft ad campaigns and make more money than 99% of fiction writers.

Or you can write for video games. Video games always need stories where the hero wins, where the path is clear, where the empire gets built, where science is a well of upgrades without downsides, where the bad guys never have a point. Literature gets the other stories, the ones that wouldn’t make a good video game, because they’re too complicated or ambiguous or dystopian.

(Of course there are dystopian video games. I’m talking trends not absolutes.)

I’m not trying to shit on Favro. Why the hell not? Even ignoring your cogent objections to all the implications she ignores, about 50% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck, with less than US$1000 in savings. That percentage is only going to increase as those robots and algorithms Favro is so enamored of eliminate an ever-larger fraction of jobs. None of those people are going to be enjoying ” the surprise and delight that comes with something new always waiting for us at the door” (Oh look! An eviction notice!) or debating the merits of lactose-free low-fat milk versus table cream.

From your quotes, this book sounds like such mindless, clueless techno-cheerleading that I assume much of it has already been excerpted in Wired.

“Except it attributes too much nobility to the starting state.”

Yeah, I’d guess, on balance, we’ve always been ignorant sons of bitches, and I doubt the Neanderthals would disagree.

It’s possible. I don’t know exactly how painful it will be, it’s very possible you’re right. But in that case, your solution won’t work either, since the social cost will be strictly higher. So shit on human nature and greed if you will, but the carbon tax is a good policy.

No, we’re totally on the same page, world is ending and we’re fucked. It’s not my field, but I can see where the consensus is pointing. I was just trying to disentangle my personal views on what *should* be done, from the objective possibilities and effects of the possible options.