I'm starting this new post both to take the weight off the old one (which is growing quite the tail-- maybe I should look into setting up a discussion forum or something), and also to introduce a new piece of relevent research. Razorsmile said

Conscious trains the subconscious until it is no longer needed..

And then Brett elaborated with

that could be how concious thought is adaptive. It doesn't do anything even remotely well, but it can do anything. It is the bridge between something you've never done before and something that you do on skill....to which I'll say, sure, that's certainly how it seems subjectively. But I have three flies to stick in that ointment:

1. Given the existence of consciousness to start with, what

else could it feel like? Supposing it wasn't actually learning anything at all, but merely

observing another part of the brain doing the heavy lifting, or just reading an executive summary of said heavy lifting? It's exactly analogous to the "illusion of conscious will" that Wegner keeps talking about in his book: we think "I'm moving my arm", and we see the arm move, and so we conclude that it was our intent that drove the action. Except it wasn't: the action started half a second

before we "decided" to move. Learning a new skill is pretty much the same thing as moving your arm in this context; if there's a conscious homunculus watching the process go down, it's gonna take credit for that process -- just like razorsmile and brett just did-- even if it's only an observer.

2. Given that there's no easy way to distinguish between true "conscious learning" and mere "conscious pointy-haired-boss taking credit for everyone else's work", you have to ask, why do we assume consciousness is essential for learning? Well, because you can't learn

without being con--

Oh, wait. We have neural nets and software apps that learn from experience all the time. Game-playing computers learn from their mistakes. Analytical software studys research problems, designs experiments to address them, carry out their own protocols. We are surrounded by cases of intellects much simpler than ours, capable of learning without (as far as we know) being conscious.

3. Finally, I'd like to draw your attention to

this paper that came out last fall in

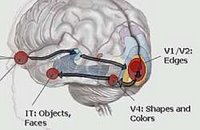

Nature. I link to the pdf for completists and techheads, but be warned— it's techy writing at its most opaque. Here are the essential points: they stuck neurochips into the brains of monkeys that would monitor a neuron

here and send a tiny charge to this other neuron over

there when the first one fired. After a while, that second neuron started firing the way the first one did, without further intervention from the chip. Basically, the chip forces the brain to literally rewire its own connections to spec, resulting in chages to way the monkeys move their limbs (the wrist, in this case).

They're selling it as a first step in rehabilitating people with spinal injuries, impaired motor control, that kind of thing. But there are implications that go far further. Why stop at using impulses in one part of the brain to reshape wiring in another? Why not bring your own set of input impulses to the party, impose your new patterns from an outside source? And why stop at motor control? A neuron is a neuron, after all. Why not use this trick to tweak the wiring responsible for knowledge, skills, declarative memory? I'm looking a little further down this road, and I'm seeing implantable expertise (like the "microsofts" in William Gibson's early novels). I'm looking a little further, and seeing implantable political opinions.

But for now, I've just got a question. People whose limbs can be made to move using transcranial magnetic stimulation sometimes report a feeling of conscious volition: they

chose to move their hand, they insist, even though it's incontrovertible that a machine is making them jump. Other people (victims of alien hand syndrome, for example) watch their own two hands get into girly slap-fights with each other and swear they've been possessed by some outside force-- certainly

they aren't making their hands act that way. So let's say we've got this monkey, ad we're rewiring his associative cortex with new information:

Does he feel as if he's

learning in realtime? Can he feel crystalline lattices of information assembling in his head (to slightly misquote Gibson)? Or is the process completely unconscious, the new knowledge just

there the next time it's needed?

I be we'd know a lot more about this whole consciousmess thing, if we knew the answer to that.

Labels: neuro, science